In his famous essay "The Hedgehog and the Fox," the philosopher Sir Isaiah Berlin identifies two types of thinkers: the fox, cunning and resourceful, knows many things; and the hedgehog, diligent and persevering, knows one big thing.

|

Berlin's formula might also be used to distinguish styles of management. Many companies focus on "one big thing," the financial performance that is every business's ultimate goal. They start with an idea of how to make the company grow, then work from the top down to get the job done. Staring straight at the balance sheet, managers decide whether to build stores or factories, crank up marketing outlays or cut costs and people.

That approach can succeed, assuming the vision is brilliant and the execution flawless. The business world has always had a few charismatic chief executives whose companies seem to prosper on the strength of sheer will alone. But for most businesses, grand plans have a tendency to unravel somewhere down the chain of command, often when front-line managers and workers fail to meet customers' expectations.

That's the problem with the hedgehog's singular vision and the benefit of the fox's wide-ranging view. The first tends to ignore the importance of human relationships in business, while the latter celebrates them. And it's the quality of those millions of one-on-one interactions -- between boss and employee and employee and customer -- that often separate businesses that thrive from those that founder.

For years, Gallup has plumbed the human depths of business. Our researchers have learned how to measure customer loyalty and employee "engagement," a nuanced gauge of job satisfaction, tracing a direct path from those human interactions to the bottom line. When customers are passionate about a brand, we have shown, they tend to try its new products and spread the word to their friends. And employees who like their jobs and feel appreciated are likely to stick around and improve their companies as they improve themselves. Paying attention to these many local human interactions helps businesses of every stripe meet that one big objective -- higher revenues and earnings -- more surely than focusing on financials alone. Gallup has even coined a term for the process of achieving this most desirable blend: optimization.

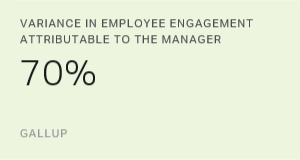

Our research on employee engagement, based on feedback from more than 1.5 million workers, was path-breaking in demonstrating the supreme importance of human interactions to the bottom line. In order for employees to feel engaged, they must know what's expected of them, have the resources to do their jobs and get encouragement from bosses. They also need to feel they have opportunities to grow and that their opinions and ideas are taken seriously. What's particularly encouraging about this research is that all of the factors that affect worker engagement are things that front-line managers can influence.

Businesses whose workers score high on Gallup's Q12 scale (so called because of the 12 questions employees are asked to measure engagement) outdistance competitors across the board. Companies with highly engaged employees have less worker turnover, stronger customer loyalty and higher sales and profit margins than do those with workers who feel less of a connection to the business.

Our research on customer loyalty also has important lessons for managers with their eye on the bottom line. The research combines two separate measures -- rational commitment and emotional attachment to a brand -- to get at the heart of customer loyalty. And it shows that proper understanding of these components can make virtually any brand capable of winning the undying devotion of consumers. Because it's more profitable to keep established customers happy than to recruit new ones, companies that use this research to guide marketing and sales strategies stand to benefit from a steady flow of capital into their coffers.

These findings are certainly compelling -- after all, they give companies the tools to improve the myriad human relationships that underlie financial success. But it wasn't until managers began asking for ways to identify their top-performing business units that these two tributaries of Gallup research, customer loyalty and employee engagement, flowed into a new river of possibilities: optimization.

Our researchers began asking whether companies with satisfied workers also were companies with throngs of loyal customers and vice versa. When the two lists didn't match -- some of the best places to work turned out to be less-than-perfect places to shop, or the other way around -- we decided to dig deeper. That's when its researchers found that business units are above the median on both employee engagement and customer loyalty often outperform those scoring the highest on just one or the other.

Consider how things played out at one national clothing retailer: a Gallup study showed that the company's stores that strived to satisfy both customers and employees had significantly better profit margins than stores that focused on just one objective or the other. Like most retailers, performance at this chain is measured by something called a conversion rate, which is the percentage of customers who actually buy something. Stores that scored in the top of the Gallup study in terms of both customer satisfaction and employee engagement had much higher conversion rates than stores that scored in the bottom on both measures. That translated into millions of dollars more in annual profits for the top-scoring stores.

Shown these results, the manager of one low-scoring store in the study made strategic changes. Ordinarily, a manager might ask a retail employee to check stock, clean up dressing rooms, or work at the register. That system does little to encourage employee engagement, nor does it put a priority on enhancing a customer's experience in the store. So the manager decided to give workers the freedom to respond to customer needs on their own. When store clerks noticed that the dressing rooms were filling up, for example, several clerks immediately moved to the registers, anticipating that customers who were trying on clothes were about to make purchases. This pleased customers, because they didn't have to wait in long lines to pay, and it made employees happy because they felt as if they were making a difference.

At another retailer, Saks Fifth Avenue, managers are in fact being trained to heed both customer loyalty and employee engagement, also with compelling financial results. Saks stores that score in the top half on both measures earn an average of $21 more per square foot, before interest and taxes, than other stores. With an average size of 103,000 square feet, optimized stores earn almost $2.2 million more each year than stores that are below-average on one or both measures. That amounts to $34.6 million more in annual earnings for optimized locations. (See "How Saks Welcomes New Customers" in the "See Also" area on this page.)

With so much to be gained financially, it makes sense to find ways to engage both employees and customers. When employees know what makes customers passionate about a brand, and when managers allow workers to seek out solutions to customers' concerns, both employees and customers benefit. Or, as Jay Redman, vice president of service selling and training for Saks, puts it: "Highly engaged associates deliver highly engaged customers."

Companies that pay attention to the quality of the human relationships at the core of their businesses stand to reap substantial profits. And the more factors they improve, the bigger the gains. So, for instance, business units that have above-median employee engagement -- that is, a store, department or division that scores in the top 50% of a company's units on that measure -- will have a 38% higher success rate, as measured by sales and earnings, than those that score below the median. Similarly, business units boasting better-than-median customer loyalty improve their chance of success by 50%, and an above-median rate for employee retention means a 70% increase in the success rate. But a unit that ranks in the top half on all three measures is a whopping 94% more successful than a store or department in the bottom half.

Such findings reinforce the concept put forth in 1996 by Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton in their book, The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy Into Action. The authors demonstrate that the best way to understand corporate performance is through a variety of factors, including human ones, rather than strictly financial data. This approach allows managers to mobilize workers in a way that channels their unique abilities in pursuit of the company's goals.

It is a powerful idea, one that has gained momentum in recent years. Our contribution has been to start with the outcome -- the hedgehog's one big thing, whether it be productivity or profits -- and to work backward, fox-like, to find the best balance of human factors that contribute to that outcome.

In his essay, Berlin describes the fox's thought process as "moving on many levels, seizing upon the essence of a vast variety of experiences and objects." That's a pretty good description of the human forces that companies must harness in pursuit of their financial goals. The lessons of our optimization research provide a map to get from here to there, to approach each relationship with a plan for making the most of a company's resources.

Or, in other words: If you're a fox about the small things, the hedgehog's big thing will take care of itself.