The Supreme Court on Tuesday upheld the state of Michigan's ban on considering race as a factor in admissions to the state's public colleges and universities, government contracting, and public employment. The ban was put in place as a result of a statewide vote in 2006. The issue is highly controversial, with critics pointing out that, as one example, the percentage of the University of Michigan's undergraduate population that is black is now 4.6%, down from 8.9% in 1995 and 7% in 2006 before the ban on considering race was put in place.

This whole area of focus on affirmative action is not only controversial, but also complex and somewhat difficult to measure using public opinion polling.

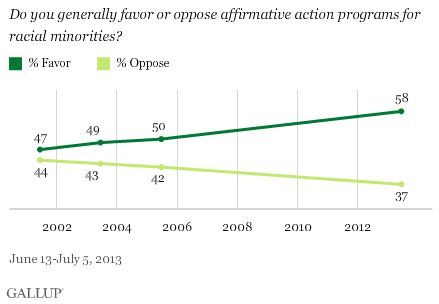

Gallup has tracked a question asking about "affirmative action programs for racial minorities" four times since 2001 and has found that Americans have each time tilted toward support of the concept -- with a big jump in support in our annual Minority Relations poll last June and July.

Support has grown from 47% in favor back in June 2001 to 58% support today. The big change in support levels came between 2005 and 2013. We can't pinpoint causality for this shift exactly, but Barack Obama's being president may have something to do with it.

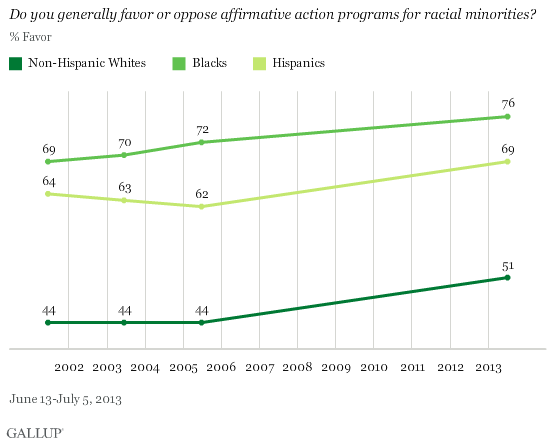

A majority of non-Hispanic whites (albeit a bare majority), three-quarters of backs, and a little more than two-thirds of Hispanics support the concept of affirmative action in principle.

The key, of course, is in the details -- exactly what does affirmative action mean and what are its practical implications? We don't define affirmative action for respondents in this basic question. What the results tell us, therefore, is that a majority of Americans' top-of-mind reaction is significantly more positive today than it is negative when they hear the term "affirmative action programs for racial minorities."

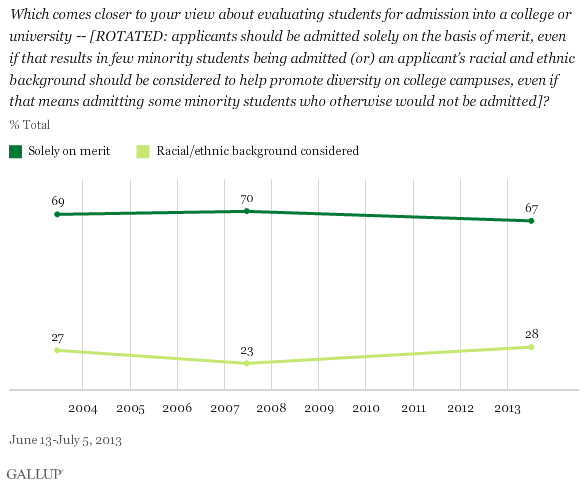

But in a different question that we used for the first time in 2003, we did put some more detail into the question, this time specifically targeted at the issue of college admissions. We re-asked the question in 2007 and again last summer. Here's the wording and the results over time.

One should read the phrasing of this question carefully. We crafted it in 2003 in an attempt to summarize the best arguments on the two sides of the issue of using race as a basis for college admission. But, as is always the case in these instances, there can be some argument with the way in which we phrased the question. One needs to constantly keep in mind that the respondents are hearing these two specific and rather complex explanations of the two positions on this issue.

The results show that when given these two choices with associated explanations, across three fielding periods of the question over the past eight years, between 67% and 70% of respondents have favored the first alternative, with 23% to 28% favoring the second. In short, the public would apparently agree with the thrust of the Supreme Court verdict in the Michigan case -- even though, of course, the average American has no idea about the legal issues which were the real basis on which the justices made their decision.

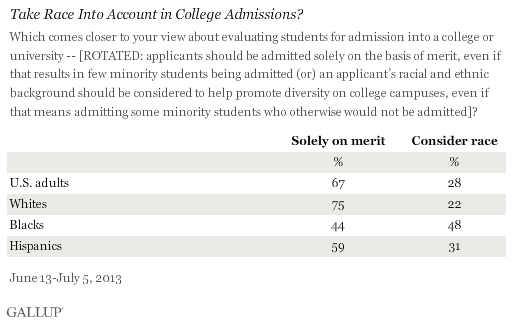

There are differences by race and ethnicity in response to the question, in the predicted direction. Whites are very solidly in favor of the "merit" alternative. Blacks, interestingly, are not equally as in favor of the "diversity" alternative, but instead are roughly divided, with only a slight preference for the "race and ethnic background should be considered" alternative. Hispanics tilt more strongly than blacks, but less so than whites, toward the "merit" side of the ledger.

My colleague Jeff Jones in his write-up of these data last summer noted the fairly large political differences in response to the question, with Democrats more in favor of the side considering race or ethnicity than either independents or, in particular, Republicans. Still, a majority of all three partisan groups favored admitting applicants solely on merit. Americans with a postgraduate education, who tend to be Democrats, also favor the considering race or ethnicity side of the equation more so than those with lower levels of education.

It's worth repeating that this is far from a simple issue. As we've seen above, 58% of Americans favor affirmative action in principle, yet only 28% say that race should be considered as a basis for college admission.

This is part and parcel of the larger issue of inequality that has been a component of the American landscape for decades and decades, and a part of the philosophic approach to the best way to arrange a social system and social structure for centuries. At issue in this situation is the correlation between certain ascribed characteristics and various outcome measures, and the desire of individuals and institutions to reduce those correlations.

College and universities have expressed a desire to consider race as a factor in their admissions policies under the assumption that a) members of some minority groups have been affected by discrimination and social structural issues beyond their control over the years and this needs to be taken into account when making an admission (and financial aid) decision, b) access to the education provided by a high powered university is a social good that should be distributed in a way that produces certain desirable social outcomes, and c) providing diversity in a student body is a reasonable goal to be considered in admissions policies since it provides a social good to all students at that university.

Clearly race is in fact taken into account by admissions officers at private colleges and universities, but public schools face different criteria -- mainly the citizens of the state who pay (in part) for the university and who can control its policies. That's what is at issue in the Michigan case.

Race is in fact but one of a wide variety of factors that competitive colleges take into account in their admissions decisions beyond just standardized test scores (which themselves are under criticism) and high school grades. These additional factors include demonstrated athletic ability, the fame of one's parents, unusual skills and experiences in non-academic areas, and the ability of one's parents to donate large amounts of money to the university. Thus, even at the most competitive colleges, a student who is listed by the football or basketball coaches as a high priority have a vastly enhanced chance of being admitted over another student with their same characteristics sans their athletic ability, the son or daughter of a president or senator has a better chance of being admitted than the son or daughter of an anonymous parent, an actress who has performed on Broadway or a musician who is already renowned for his cello playing have better chances that other similar students, and a student whose parents are very rich and who promise to give lavishly to the university has a better chance than others. Children of alumni also get a boost in their admissions chances.