What's the most powerful marketing weapon in a company's arsenal? A well-paid advertising firm? A good word from Wall Street analysts? Its employees? Sure, all of these assets are beneficial. But the most valuable marketing tool for any company is one that money can't buy: a loving customer.

|

So says William J. McEwen, Ph.D., author of Married to the Brand, out last month from Gallup Press. As a Gallup global practice leader, McEwen has directed strategic brand and marketing research for many of Gallup's largest clients, including those in the automotive, retail, telecommunications, and high technology industries. And before he joined Gallup, Dr. McEwen worked in the advertising trenches at McCann-Erickson, FCB, Leo Burnett, and D'Arcy, on everything from beer to banking.

All that experience in marketing, advertising, and the psychology of consumer relationships has led Dr. McEwen to a startling conclusion: In companies' desperate struggle to gain market share, customers have been forgotten.

This is a problem that many organizations find familiar, and it's a bad situation for companies and customers. Companies must promote their brands, so marketing executives continue to pump huge portions of their budget into advertising. But customers are growing increasingly resistant to traditional marketing efforts; they're also growing skeptical, cynical, and even hostile to brand messages. And yet, as Gallup's research shows, the most profitable customers are the ones with an emotional attachment to brands -- emotional attachments so strong they resemble marital bonds.

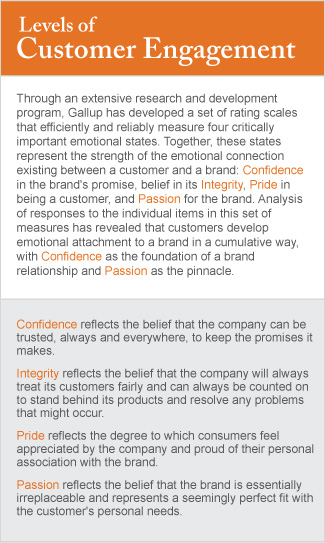

So how can marketers turn skeptical customers into loving "spouses"? On one hand, the answer may seem simple. All brand bonds are built on a foundation of four emotions: Confidence, Integrity, Pride, and Passion, Dr. McEwen says. But building and reinforcing those emotional connections is where it gets complicated. In this interview, Dr. McEwen simplifies the complexities of brand bonds, explains how to cultivate them, and discusses why most companies fail to create bonds with their customers. Some don't even try -- leaving the field, and their consumer base, wide open to the competition.

GMJ: In speaking about brand loyalty, you use a marriage analogy. Why?

Dr. McEwen: All great marriages involve a powerful emotion: passion. So do all great brand relationships. These brand connections transcend behavior -- simply buying a brand -- and involve emotional bonds that are akin to the feelings people associate with a marriage. As companies look to create enduring connections with customers -- we call this customer engagement -- the metaphor that springs to mind is the one that best exemplifies a strong, enduring connection, and that's a marriage.

GMJ: So, what's the benefit to a business of an engaged customer? Why should businesses care if customers are "married" to their brands?

|

McEwen: That's the ultimate question, and the obvious initial response is, "So, big deal. Why should we care?" Here's the answer: Engaged customers are simply more lucrative. They'll stay with you longer, they're less sensitive to price, and they won't switch brands unless they absolutely have to. They'll shop at your stores more often, they'll pay a premium for your brand, and they'll give you the benefit of the doubt when something goes wrong. When it comes to positive word-of-mouth endorsement, they're often worth their weight in gold. They're the evangelists, advocates, and bloggers. The most powerful marketing weapon that a company can have is an engaged customer.

GMJ: What creates that level of engagement? What prevents brand "divorce"?

McEwen: Engagement is both a rational and emotional connection between a customer and a brand. (See sidebar "Levels of Customer Engagement.") The foundation of this relationship is Confidence. Fail to deliver on Confidence, and ultimately the relationship is not only in jeopardy, it's likely to deteriorate. Then there's Integrity -- the belief that if anything goes wrong, "I know you'll stand behind it. I know you'll fix it. I know I can count on you." Third is Pride -- a reciprocal feeling that "I'm proud to be here, and you're proud to have me." And then ultimately, there's Passion -- "I consider your brand irreplaceable in my life. I don't need to look anywhere else, and I don't want to look anywhere else."

Back to the marriage metaphor -- that's what a good marriage is. A marriage without a bedrock of faith and confidence in each other is doomed. In a brand relationship, I don't believe that Passion is possible long-term without Confidence. That's divorce court. You must have strong feelings of Confidence, Integrity, Pride, and Passion to be engaged with -- or married to -- a brand.

GMJ: How does a brand create Confidence, Integrity, Pride, and Passion?

|

McEwen: The first step is creating a powerful brand promise -- but, important to note, a promise you can actually keep. BMW, for instance, has maintained a singularity of focus on its brand performance and on how the product handles. A BMW feels and drives like a BMW, always.

The problem comes when companies look to reach beyond where they currently are and try to be everything to everyone. Most companies have a difficult time sticking to a core brand promise because they're always looking to expand their customer base, either by entering new territories or introducing new products -- thereby reaching previously untapped markets.

However, in doing that, a brand may expand its promise to the point that it loses its core meaning. It risks looking like Chevrolet, with a small Chevy and a big Chevy and a fast Chevy and a truck Chevy. Then suddenly, customers are wondering, "What's a Chevrolet?" At that point, the brand promise becomes fuzzy -- even generic. You don't want your brand to be just a hotel, just a car, just a bank -- you want your brand to be clearly differentiated in what it offers customers, emotionally as well as rationally.

The only way to differentiate the brand is to begin with a well-articulated brand promise -- by saying exactly what it is that you want your brand to be and how that makes it different from all other brands. Then, of course, comes the really hard part. You have to think about every one of your customer touchpoints and ask yourself, "Just how well are we delivering on that core promise?" If you're not delivering on your core promise, you might as well forget about making the promise. A promise unfulfilled cannot support a brand marriage.

GMJ: What happens to customers when they feel the brand promise has been broken?

McEwen: If your business message bounces from "We're this" to "We're that," you confuse your current customers, your prospects, and importantly, your own people. When this happens, employees don't know exactly what they're supposed to be delivering or how they're supposed to deliver it. Your current customers may feel that, in its pursuit of new markets, your company doesn't care about them any more. One of the first requirements is to articulate what your promise is, how it makes you different, and exactly what that implies for all the people who work for you.

|

GMJ: So how do similar businesses differentiate themselves? For instance, how do Lowe's, Menards, Home Depot, Ace Hardware, and all the smaller do-it-yourself stores differentiate themselves when they all sell the same thing to the same market in the same town?

McEwen: It's not easy . . . but there's really no alternative. If you don't differentiate what you carry or the nature of the service you provide, the only thing that will differentiate you from anyone is the prices you charge or the location where you've built. So, as others have also said, you must either differentiate or die. You may do this by focusing on a market segment -- perhaps a demographic such as young families or women; perhaps a psychographic or occupational segment, such as fumblers, experienced home remodelers, or contractors. In doing so, you must walk away from some customers, or you become a business that wants to be all things to all people. When you try to be the place where everyone goes, you can become the place, to some degree, where nobody goes -- unless you're lucky enough to become the one base brand that defines a category.

GMJ: Like Wal-Mart.

McEwen: To a degree, of course, just like Wal-Mart. And if you think you're going to beat their price point, good luck. But even Wal-Mart is about much more than just price. Like any great retailer, Wal-Mart cannot rely on a single feature to maintain brand differentiation. Competitors stand ready to imitate whatever you do, and almost everything tangible is duplicable.

GMJ: So your business has come up with an unshakeable brand promise and a solid differentiator. Now how do you "court" customers?

McEwen: At their foundation, brand bonds are both rational and emotional. Everybody has "reasons" for why they choose a particular brand, and those reasons are both logical and rational -- "I fly that airline because they fly where I'm going at a reasonable hour for a reasonable price." But the reasons are also emotional -- "I use that airline because it's more than just a flight going where I want to go at a reasonable price. Unlike the other airlines, it's actually fun to fly with them. I fly them because it makes me feel good."

We often misconstrue emotions as being irrational and even irrelevant, but emotions are very, very powerful. Human beings are delightfully -- and quite sensibly -- emotional. Even their investment decisions, as Daniel Kahneman has pointed out, are influenced by emotion. [Dr. Kahneman, a psychologist, won the 2002 Nobel Prize in economics; see "What Were They Thinking?" in the "See Also" area on this page.] The concept of an economic being who makes decisions based purely on some sort of strict calculus of economic value is just not true. With humans, emotions are always involved. The problem has been that emotions have seemed squishy and hard to measure, so many businesses have just left it up to their advertising agencies to throw a little emotion into the mix -- to put a little sex on the car, to make the airline look like fun, to show those skies being friendly -- even if they aren't.

GMJ: A company's agency adds the sizzle to the steak.

|

McEwen: That's exactly right. The agencies have essentially said, "Our job is sizzle; your job is steak." But no company should outsource the responsibility for creating emotional connections -- they're too important, too valuable, to a brand. You see that most clearly in service businesses where there are people involved. Business has moved from traditional product marketing to a world where service is what's being sold -- and whenever service is a key component of what you're marketing, your world changes, and your brand management challenge intensifies. Whether you're Lexus or Ritz-Carlton or Starbucks or Wal-Mart or The Bank of New York or Deloitte Touche -- no matter what your company is selling, you deliver that product through people. And people are the most challenging, the most frustrating, and the most diverse factor involved in creating and supporting brand marriages.

If I'm in charge of Crest toothpaste, and I change the package tomorrow, all the Crest toothpaste around the country will appear in that same redesigned package. It's really not that big of a deal. But if I decide I'm going to change the way in which I handle my customers at Starbucks tomorrow, it's much more complicated, because I've got to completely change the systems, the support programs, the training, the way I hire and manage, everything, because my people have a huge role in creating the emotional bond I have with customers. So as we move into a brand world where service is what we're selling, then the highly diverse touchpoint called people comes into play. And people are the ultimate challenge.

Now the problem for brand managers is that traditionally, they're in charge of the product, the packaging, maybe the pricing, and certainly the promotions -- but they haven't had much to do with the people. That's been an HR or operations issue, and brand managers haven't been directly involved. But people -- for any marketer where service comes into play -- are where brands become most sharply differentiated from one another. That's because service is the toughest thing for companies to duplicate. Other brands can mimic your price. Within limits, they can clone your product. They can create the same kind of store layout, and they can imitate your processes and policies. But people defy duplication.

GMJ: How can a company with a lot of customer-facing employees differentiate on service and keep it consistently good?

McEwen: Again, doing what's easy isn't enough. Only the companies that can accomplish the truly difficult tasks -- and do them consistently -- can hope to establish an atypical relationship with their customers. But how are they supposed to do that? I would say that their efforts may start at the top, but they must thoroughly permeate the entire organization. They must be felt at every customer touchpoint. And that's tough.

I've often talked about Ritz-Carlton as a company that successfully does that. In some ways, their promise isn't all that different from the one that a Hilton or a Radisson or another nice hotel makes. The difference is that Ritz-Carlton executes. The head of Ritz-Carlton has stated that customer engagement is driven by factors that are not additive, but are rather multiplicative. It is people times product, not people plus product. The best product in the world delivered by rude and uncaring people cannot support a customer connection. Anything times zero is zero. The reason that Ritz-Carlton, Lexus, and Starbucks succeed is that they are able to create greater uniformity of touchpoint performance than their competition, who often give up because it's just too tough.

When it comes to customer engagement, greatness times greatness is huge. This isn't a secret -- in fact, Ritz-Carlton puts on seminars to explain The Ritz-Carlton Way, knowing full well that people will walk away impressed, thinking, "Boy, I wish we could do that, but in my company that won't work. We're not structured that way, we don't have that culture, and we don't have that degree of commitment from on high."

All of the auto companies admire BMW and Lexus for the obvious customer passion they've managed to achieve. Lexus says that it's more than the product; their product is terrific, but it's not enormously different from other $50,000 vehicles. But the experience of owning a Lexus is different not just because of the product, but because of the contribution made by the dealer network. Other automakers want to create that level of customer engagement, too, but they cannot duplicate what Lexus provides through its dealers. In some cases, the competing company and its dealers appear to be heading in different directions.

GMJ: How, then, does a brand manager manage the people? How can a CEO manage the guy at the checkout stand?

McEwen: To begin with -- and it's only a starting point -- I believe companies ought to have a chief customer officer.

GMJ: A new C-level position?

McEwen: Yes. Companies need someone with real clout and a genuine passion for the customer that cuts across corporate silos. They have product designers, promotions managers, sales managers, human resources managers, and perhaps a store operations group. That's fine -- companies need people that will focus on issues that deeply affect the operation of the individual silos. But customers don't experience brands one silo at a time. They don't say things like "I really like the wrapper on that snack, but I don't like the snack." They don't say, "Gee, I really like the colors that United is using on their airplanes, but the baggage handlers lost my luggage." They have a visceral overall reaction.

A chief customer officer would have the resources to manage both the statement and the execution of the brand promise at all touchpoints. I'm also convinced that customer engagement scores should be monitored by Wall Street analysts every bit as closely as current financial performance metrics. That's because customer engagement tends to be a bellwether of future performance, while current financial performance tends to reflect what companies did in the past.

GMJ: One last question: What kind of car do you drive?

McEwen: A Mini Cooper. I could come up with lots of rational reasons for it, but I'll also acknowledge the fact that it just looked cool and felt great to drive. I could immediately see myself behind the wheel. Now that's an emotional connection!

-- Interviewed by Jennifer Robison