Measuring employee engagement is essential for companies that want to perform at their peak. But let's be clear about one thing: Measurement doesn't cause engagement.

Top-down solutions may produce clarity, but they don't inspire buy-in or practicality.

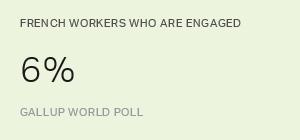

Many companies use Gallup's Q12 employee engagement survey to measure engagement at the workgroup level, which gives them insight into where engagement is strong and where it can improve. But simply measuring engagement will not cause managers or employees to be engaged. Engagement is the result of many factors, including individual and team commitment to improving the workplace.

One proven strategy to increase engagement is action planning, a process that managers and their teams use to make plans and take action based on their Q12 results. I've spoken with hundreds of managers about engagement and action planning, and I've found that managers ask me these two questions more often than any others: "How do I get my team to buy in to action planning?" and "How do I make it practical?"

These are reasonable questions. Managers want to fix problems. They want to isolate the engagement problem, find a solution, and implement it as soon as possible. Meanwhile, their employees are watching them, wondering if this is just another one-time survey or if this is a long-term process that will finally identify and correct problems that need to be fixed.

That's why so many well-meaning managers jump right in to interpreting numbers from a report, often choosing areas of focus without involving their teams or considering business outcomes. So when managers complain that their team hasn't bought in to their plan, I ask a question of my own: "Whose plan was it?" Usually, the response is something along the lines of, "Well, it was mine."

Top-down solutions may produce clarity, but they don't inspire buy-in or practicality. That's because top-down decision making about engagement fails to recognize the varying dynamics among workgroups. More importantly, it misses an opportunity to engage teams in creating and "owning" their own solutions.

Engagement is a process

Engagement should be treated as a process, not a one-time event; it is an indicator of a workgroup's fitness, not a stand-alone outcome. Engagement also requires intentionality and a scalable structure. Managers and employees need to be involved in the action-planning process, and the process must be replicable. But too many managers approach building engagement as they would choosing a cellphone carrier: They consider the variables, make a decision, and move on until the contract expires, neglecting to seek feedback from people who have actually experienced the carrier's service.

I've listened to the difficulties managers face trying to create meaningful action plans, and I've heard everything from excuses like "We don't have time for this" to legitimate concerns such as "It's tough because my team is located in five different sites across three time zones."

Through conversations like these, I've found that the following five questions are a practical approach for thinking and talking about engagement. They also ensure maximum participation, practicality, intentionality, and scale. I have asked managers these questions many times, and I recommend that managers use them with their teams immediately before sharing their Q12 survey results. For many managers and teams, they have become an essential part of the action-planning process.

Question one: How do we define each of the Q12 items in our workgroup? For example, how do we define "materials and equipment" for our team?

Gallup's Q12 is a 12-item measure of employee engagement, and each item addresses a specific element of engagement. These items include statements such as "I know what is expected of me at work," "I have the materials and equipment I need to do my work right," and "My associates or fellow employees are committed to doing quality work."(See sidebar "The 12 Elements of Great Managing.")

Individual workgroups have different cultures and needs, so they should discuss what they think about each element of engagement. The temptation here is for companies to define what Q12 items mean in the organization. But a better approach is for managers to ask their teams how each specific item applies to the realities of their particular workgroup. Managers should ask their team this question, then pay close attention to what emerges from the discussion.

For example, I consulted with a large technology company that had recently experienced a round of budget cuts, and travel had been frozen. Their remote workers were most likely to cite videoconferencing when defining the materials and equipment most important to them. Most managers weren't surprised by this, but they varied widely in how they responded to this feedback. Predictably, managers who dismissed videoconferencing as too expensive or as outside the realm of their control were those with the lowest levels of engagement relative to their peers.

Question two: Now that we defined each of the Q12 items for our workgroup, what would the ideal look like for each item?

Making engagement happen isn't just a manager's responsibility.

Sometimes, I'll encourage managers to dream a little with their teams. If budgets didn't exist, for example, what would the ideal materials and equipment be for their team? Often, the answers are surprisingly mundane -- workgroups rarely want what's impossible, even when the sky's the limit.

Many managers are hesitant to have this discussion with their workers, citing that it might create false expectations or set an impossible standard. This hesitation, however, is unfounded. The purpose is not for the team members to say, "If we have x, we'd rate this item a 5." Instead, the purpose is to establish aspiration and ownership, empowering the team to consider what their efforts might achieve and creating a benchmark to which the team can aspire.

For example, despite the budget realities that many teams face, many of the managers I talk with have generated new ideas for remaining connected using existing materials and equipment, such as emailing a "question of the day" about the company to members of their teams or using videoconferencing in addition to conference calls to create face-to-face connections. When the teams dreamed a little, they often found they already had the materials and equipment they needed to solve the problem.

Question three: What is the difference between where we are now and that ideal?

Having established what the ideal looks like, the team can take the bold step of asking how far away from it they are. This process affords opportunity for celebration, building on previous successes, and establishing best practices. It also promotes candid discussion and creates an environment where team members can share and support their views. This helps teams grow and mature and gives everyone a chance to claim responsibility for areas that might lie within their control.

After we talked about how to use these questions, one manager conducted his action-planning meeting and reported back. "I told the team where I thought I'd been getting in the way and admitted some mistakes I'd made over the last few months," he said. "It was hard, but I think the team appreciated it." This kind of transparency builds goodwill and creates a platform for more open dialogue.

Question four: As we think about our action plan, which items have the greatest impact on our culture or performance?

Engagement must be tied to performance because it benefits businesses in tangible ways. Otherwise, the exercise and conversation are pointless, and employees will rightly wonder why they must participate in activities that have no real purpose or practical utility. Again, measuring engagement shouldn't be an end in itself.

Making engagement happen isn't just a manager's responsibility. As employees identify aspects of culture and performance that would benefit from increases in engagement, they begin to think in solution-oriented ways. They begin to own the culture, their performance, and their own engagement.

This question also grants vital permission to take the discussion further. Managers and teams start asking themselves more questions, such as: "Is it OK to prioritize some items and defer others based on the team's stated objectives?" and "What items are most likely to drive those objectives?"

As I debriefed with a manager after a recent action-planning session, he told me that the team had chosen to focus on the item "My associates or fellow employees are committed to doing quality work." They chose this item because their team both depended on and served internal customers, and they thought that improving in this area would shorten wait times for their stakeholders and improve their internal brand, which had suffered recently.

It's neither advisable nor desirable to include every item in an action plan. It's far better to focus on the items that will bring the greatest return on invested time and effort at a particular time, because the team's needs and circumstances will change. Every element of engagement is important and links to key business outcomes. But using this question to narrow the focus to a few key items will reveal what is important for the workgroup now.

Question five: What is every person on the team willing to do about engagement?

Too many companies treat engagement like an a la carte menu from which the manager chooses everything. If an engagement process results in open dialogue among the team members and the team identifies expected outcomes and areas in which to invest, yet the manager is the only person who leaves the meeting with a to-do list, then action planning has failed.

A good action-planning meeting is one in which every attendee leaves with a next step. Each member of the team must contribute and have a role to play. People are more eager to invest in ideas they helped generate than those initiated from the top down.

In addition to creating accountability, this question also enables the team to decide that some ideas, though compelling, have too many barriers to implement immediately, while others present more positively. For example, budget limitations might make travel or the purchase of new equipment difficult. While these options should be explored, they might not be part of the final action plan as a result.

Engagement isn't solely a manager-driven outcome

When used as a template for action planning, these five questions yield the critical elements of buy-in and practical action. They also help dispel the myth that engagement is solely a manager-driven outcome. While managers can influence engagement, they can't be expected to generate it alone. Managers who use these questions will get associates involved by creating a conversation. By treating engagement as a process, not an event, they tie engagement to actions that produce cultural improvements and business outcomes.

Five Questions for Action PlanningThese five questions offer a practical approach to help managers and teams think and talk about engagement. They work best when managers use them to start a discussion with their teams immediately before reviewing their Q12 employee engagement survey results and to develop an action plan to increase engagement.

|