Within a five-minute walk of my Greenwich village apartment, at least five restaurants serve strong coffee and excellent sandwiches at low prices. CEOs could learn a lot from the reasons I keep visiting my favorite -- even if it's overflowing with customers every weekend. (It's true that multinational corporations have more moving parts than coffee shops, but bear with me.) My favorite place doesn't advertise, offer membership cards, or dole out rewards for frequent visits. But the waitresses candidly suggest the best quesadilla fillings, the owner has bused our table, and a waitress once let my wife borrow a cell phone when I was out and she'd forgotten her keys. It's not just that I know I'll get good value and a pleasant experience every time I'm there. I trust the staff with my time, my money, and my friends. I'm beyond satisfied with this brand: I miss it when I go too long without it. I'm attached.

|

Corporations have spent billions of dollars trying to make customers as loyal to their products and services as I am to that coffee shop. Ever since consumers on market research panels began weighing in on everything from cereal crunchiness to shampoo viscosity, companies have tried to tailor products to meet shoppers' preferences. More recently, as the Internet and other channels of electronic commerce became common market-research tools in the mid-'90s, businesses have tracked what individual customers buy -- and don't buy. Now, with all that information at their fingertips, executives have been trying to figure out which business practices make faithful customers loyal. Yet an understanding of why customers stick with a brand is still evolving. Mainly, managers know what they don't know.

Today, the search for the ties that bind customers to brands has taken on fresh urgency. The equity markets are volatile and venture investors are chastened, so loyal customers represent a company's best prospects for pumping capital into a business. Unlike stock appreciation, which can fluctuate wildly over the short and medium term, loyal customers can be counted on to build a solid base of revenues as well as to expand profits.

Such customers are likely to try new offerings and to provide strong word-of-mouth for a brand, saving companies advertising and product-assessment costs. So it's not surprising that customer loyalty ranked first among the management concerns of CEOs in this year's Conference Board survey, a widely watched gauge of hot-button issues across a range of industries.

|

But what is it that actually makes customers loyal? Simply satisfying them certainly isn't enough. Implicit in management legend W. Edwards Deming's call for continuous improvement -- articulated in his 1986 work Out of the Crisis -- is the idea that a customer who is satisfied today may have a different set of needs tomorrow. Since then, and especially in the past five years, marketing scholarship has established many times over that satisfaction scores alone fail to predict how customers will actually behave.

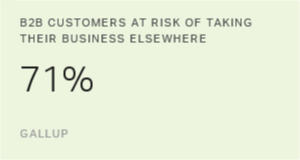

Part of the problem is that satisfaction scores measure only past experience. The American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI), for instance, plots whether a customer thought she received good value -- whether, for example, a computer is as functional or a hotel room as clean as she expected it to be. The index reflects a rational assessment at a particular moment. But it fails to capture either the customer's intentions -- whether she would recommend the brand to others -- or emotions. People stay faithful to brands that earn both their rational trust and their deeply felt affection. That dynamic, which Gallup has studied extensively, turns out to be a better predictor of behavior than consumer satisfaction measures alone.

Return for a moment to my coffee shop. Shortly after I moved to the neighborhood, my wife and I tried a similarly priced competitor that had delicious omelets, fresh bagels and attentive counter service; I would have given the place a high satisfaction score. Yet I've hardly ever been back. My emotional attachment to my favorite place -- how it makes me feel, how I interact with its staff -- matters more to me than whether I get better value elsewhere.

In the past few years, a marketing discipline has evolved to capture this distinction. Frederick F. Reichheld, author of the widely read The Loyalty Effect: The Hidden Force Behind Growth, Profits and Lasting Value, showed that making loyalists out of just 5% more customers would lead, on average, to an increase in profit per customer of between 25% and 100%. Reichheld's analysis showed that the cost of acquiring new customers was five times the cost of servicing established ones. The implication is that managers who depend on all manner of snazzy products and flashy ad campaigns to lure new buyers will always be playing catch-up with companies that concentrate on keeping established customers happy. Ever since, marketers have stopped looking for satisfied customers and begun focusing on loyal ones. But how does a company forecast who will be loyal and who won't?

|

That's where Gallup's new 11-question metric of "customer engagement," called CE11, comes in. CE11measures rational formulations of loyalty according to three key factors (L3): overall satisfaction, intent to repurchase, and intent to recommend. But it also adds eight measures of emotional attachment (A8). "The total score, which reflects overall customer engagement, or CE11, is the most powerful predictor of customer loyalty we know," says Gallup senior consultant John Fleming, Ph.D.

Gallup's research into the dynamics of rational loyalty (L3) and emotional attachment (A8) to a brand began with testimony from the customers of a world-renowned theme park. Gallup found that, despite agonizing waits for rides, high prices and imperfect service, customers, by and large, remained loyal to the park. "Expensive food and long lines made me want to tear my hair out," said one customer, sounding exasperated with the park. "But when I looked down and saw the joy in my children's eyes, it was all worth it." That customer's emotions had trumped her reason; the brand had managed to create a sense of magic that transcended the park's shortcomings.

There is more to this, though, than just magic dust. When a brand inspires both rational loyalty and emotional attachment, customers will continually reward it with their business. Consider a Gallup study of a major hotel chain's affinity club. All members have rational incentives to spend more of their lodging dollar with the chain, because they qualify for perks and discounts when they spend more. Yet some members spent more than others. Affinity club members who were strongly attached gave the chain 32% more of their total lodging dollars than did those who were not emotionally attached.

But CE11doesn't identify just attached customers of theme parks or luxury hotels. Its questions let customers of any product raise signs above their heads, declaring themselves the most eager buyers in the bazaar. The L3establishes a customer's rational disposition toward a brand. Then the A8 captures what goes on in that customer's psyche when a product earns her confidence and coincides with something so useful or so delightful in her experience that it becomes a touchstone of her day. When L3and A8 scores are high, the customer seeks out the brand even when she doesn't necessarily need to replenish her supply. The statistical science behind the A8 captures the sequence in which that kind of emotional attachment develops.

Gallup developed the eight A8 questions as paired indicators of four emotional states: confidence in a brand, belief in its integrity, pride in the brand and passion for it (see the table below). An analysis of responses to the questions revealed that customers develop emotional attachment to a brand in a cumulative way: customers who agreed strongly with the first two statements of the A8 were more likely to agree with the next two, and so on.

|

||

|

EMOTIONAL ATTACHMENT (A8)

IS CONSISTENT ACROSS INDUSTRIES (EXCEPT AIRLINES) . . .  |

|

|

||

|

||

When customers agreed strongly with both statements about a brand's reliability -- "this brand always delivers on what they promise" and "this brand is a name I can always trust" -- they were demonstrating their confidence in the brand. Confidence normally precedes more intense feelings of attachment, because it determines whether a customer feels secure about a brand's utility.

A bank, for instance, will draw low scores on confidence if its monthly statements are sometimes inaccurate or if its tellers stare blankly when customers ask about the bank's investment or credit-card offerings. And an offer to "fly the friendly skies" will inspire confidence only if the flight attendants remain friendly every minute the customer spends in the sky.

To build confidence, then, a manager needs to strive to keep a brand's marketing message in sync with the product or service the company delivers. Gallup found that among members of a hotel affinity club who said they got less from their membership experience than they thought they would when they enrolled, not quite one in 25 was confident in the brand. Compare that to the customers who said the membership matched their expectations: one in four was confident. The lesson is clear: When customers get less than they expect, they're unlikely to have confidence in the company -- and we've seen that confidence is a precursor to long-term loyalty and emotional attachment.

Belief in a brand's integrity -- gauged by whether a customer feels fairly treated and by whether she expects a fair resolution to any problems she encounters -- follows. That belief is reinforced when a customer feels she is dealing with a company that is not only competent and forthright but also fair and ethical. It can be instilled, for instance, by a salesperson who steers the customer to a product she says she wants instead of dumbly pushing the most expensive merchandise. Similarly, if a desk clerk botches a room reservation, he should know to offer an upgrade or some other token of apology.

When such practices become commonplace -- when a customer can count on getting reliable service and when she knows that someone will make amends if she doesn't -- then she feels proud of the brand. (Pride, in Gallup's classification, reflects the customer's strong sense that the brand treats her with respect and that she, in turn, feels good about using it.) High scores on pride questions indicate that a customer has crossed a threshold of commitment to the brand. We can all think of brands with which customers proudly identify -- luxury brands such as Rolls Royce, as well as discount brands such as the Sam's Club unit of Wal-Mart. It's no coincidence that both enjoy reputations for treating customers with deference and respect.

When a customer wears a logo on her backpack or drops a brand name in cocktail-party conversation, she has reached the highest rung of emotional attachment: passion. Customers with passion strongly agree with the statements "This brand is the perfect company for people like me" and "I can't imagine a world without this brand." They would never take a trip to the beach house without stocking up on their favorite soda; they will travel a little farther to find their preferred motor oil. That level of attachment corresponds to growing revenues: One Gallup study, for instance, demonstrated that a mid-size bank could add $265 million to its total of customer balances on deposit just by drawing higher attachment scores from 50,000 more customers.

Passionate consumers have been known to wage public campaigns protesting a change in a soft drink formula, indicating a depth of commitment that moves beyond loyal to fanatic. And that level of passion can by sparked by goods as everyday as hiking boots or potato chips. Indeed, Gallup research across a range of industries -- from online retail to airlines to banks -- found that roughly one in 10 customers in every industry is passionate. So the excuse of being in a "boring" business no longer absolves managers from bonding with customers who make brands integral to their lives.

When a brand communicates that it deserves consumers' trust, it can draw passionate believers even in a reviled industry. That's the lesson of Southwest Airlines. In another Gallup study, Southwest saw 27% of its customers fully engaged, compared with 7% for Delta and 5% for United. You'd expect a customer to feel emotionally attached to the car in his driveway (or the retailer he visits on weekends), but the airline delaying his trip home? Clearly, Southwest, like Wal-Mart, has managed to communicate an emotional appeal that its competitors lack -- an appeal that has relatively little to do with the specific natures of their respective markets.

It's no coincidence that both brands focus on service in ways that can make an often-frustrating experience pleasant for customers. Southwest, with its wisecracking flight attendants and small-city jet service, cultivates an image of fun in an industry that's full of delays and inconvenience. Wal-Mart banished the surly clerk who haunts so many discount retailers and replaced him with a friendly greeter, often a senior citizen instead of a resentful teen. Such service features often inspire high emotional attachment because they improve the odds that a customer will experience each of the four emotional states that drive A8 scores.

At the top of the A8 ladder, a passionate customer can -- and will -- shower dollars on a brand. But on the ground, a manager has to figure out how to persuade uncommitted customers to move up the rungs of that ladder, from provisionally satisfied to rationally loyal to emotionally engaged. Gallup's research has revealed three powerful ways managers can reach that goal: 1) creating products that are as flawless as possible; 2) training employees to act as ambassadors of the brand; and 3) transforming problems into opportunities to please customers.

|

Flawlessness may seem unreachable, but practical steps can be taken to come close. For banks, flawlessness includes ATMs that always work, customer service reps who offer up-to-date information on rates, and back-office staffers who rectify errors quickly and courteously. For airlines, flawlessness means on-time performance, clean and modern aircraft, and pleasant terminals.

One way to encourage the perception of flawlessness among customers is to instill in salespeople and customer-service personnel the belief that the wares they offer are as close to perfect as possible -- and always improving. (Actually, a manager should instill this sense in all employees, it's just that sales and customer-service people have more opportunities to cultivate it among customers.)

Another strategic lever that emerged from Gallup's research calls on managers to direct front-line staffers -- call center operators, desk clerks, floor salespeople -- to communicate fairness and respect. Consider: A surly or clueless desk clerk can sour a customer on a hotel chain, especially if that chain advertises its comfort and friendliness. Managers should also make sure that front-line employees' behaviors and the promises they make on behalf of the brand are fully aligned with the company's marketing message. When an employee clearly doesn't buy into -- or even understand -- a brand's promises, it's hard for customers to become convinced that the brand has integrity. If managers select, position, and train employees to delight customers and reward them for doing so, customers will become emotionally attached simply by conducting business with the brand.

The third strategic lever is perhaps the most surprising. When customers experience problems -- say, a service glitch or a faulty product -- a funny thing happens. Companies that deal quickly and thoroughly with customers' problems tend to arouse passion in their customers just as surely as companies that never create problems at all. Southwest Airlines' customers, for example, say the airline effectively deals with problems in 77% of cases, compared with less than 50% for the four largest carriers. As a result, nearly half of those who say they are loyal to an airline identify Southwest as their favorite.

Great companies become great by cultivating distinct brand identities. CE11offers an analytical tool for gauging how that brand resonates in the marketplace. It enables companies to clearly see the path from its products and services to the hearts, minds, and wallets of its customers.