What should the role of government be in the arena of race and race relations in the U.S. today? This question has moved into the national conversation again after the recent events in Ferguson, Missouri. Representing the U.S. government, Attorney General Eric Holder flew to Ferguson recently to look into what the federal government could or should be doing to ameliorate the types of situations that occurred in that city when a young black man was shot and killed by a white police officer. A recent Politico story, for example, focused on the possibility that the situation in Ferguson could result in changes in police procedures and other aspects of race relations that might help prevent such a situation in the future.

Historically the federal government has been at the forefront of bringing about change in race relations in this country, extending back not just to the President Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War, but more recently to President Harry Truman's integrating the armed forces, presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy sending in federal troops to control situations with high racial tension, and the historic Civil Rights Act passed under President Lyndon B. Johnson. But with many overt or legal race barriers now removed by law, and with a wide ranging federal apparatus for adjudicating cases of race discrimination, the issue remains as to what additional actions or steps the federal government or other levels of government could or should take relating to race. Some proposals that have developed out of the Ferguson situation so far have focused on the Defense Department's program of providing excess military equipment to local police departments and the possibility of a federal effort to require police officers to wear vest cameras while on patrol.

A review of our data from last summer's major Minority Rights and Relations poll helps shed light on Americans' views on the general question of how much government should be doing in the realm of race relations. The poll included updates on many Gallup trends relating to race and involved samples of 1,010 blacks and 2,149 non-Hispanic whites.

The results show that blacks are significantly more likely than whites to argue that government intervention is needed in the realm of race relations and civil rights, but that there is by no means a consensus within blacks that more such actions are needed.

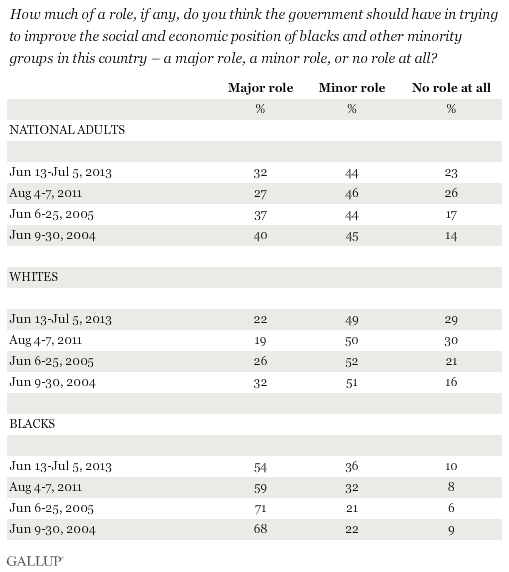

This conclusion is based first on this key question: "How much of a role, if any, do you think the government should have in trying to improve the social and economic position of blacks and other minority groups in this country -- a major role, a minor role, or no role at all?"

The responses showed that 22% of whites agreed that the government should have a major role, contrasted with 54% of blacks. This question allowed three responses, and while one in three whites say "no role" for the government, almost half say a "minor" role. Thus, one way of looking at this is to say that the significant majority of both whites and blacks agree that the government should have some role to play in improving the social and economic position of blacks and other minority groups in this country. The difference comes in the degree of involvement, with whites tilting to a "minor" role and blacks tilting to a "major" role.

Note also that the view that government should play a major role in improving race relations has been decreasing over the four times that we've asked this question since 2004 -- among blacks a drop of 14 percentage points and among whites 10 points. (Whites' "major role" percentage did tick up over the last two years, however, while blacks' continued to drop.) Our latest data point on this trend came from last summer, way before the Ferguson situation, but clearly as of that point the perception of a need for government to play major role in race relations had been dropping. This could, in part, reflect the fact that the country has its first black president in history and as a result an increase in perceptions that the country has become more racially tolerant.

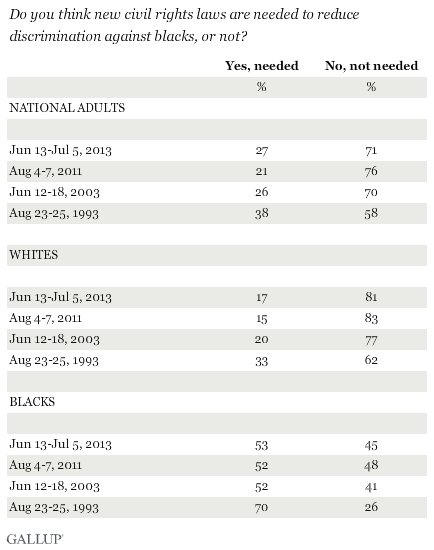

Gallup has asked Americans four times since 1993 about the need for new civil rights laws. Overall, as of last summer's survey, 27% say that such new laws are needed, while more than seven in 10 say they are not.

Again, blacks are more than three times as likely to say "yes" than whites. When Gallup first asked the question in 1993, after several years of focus on trials associated with the Los Angeles police beating of Rodney King, the percent of both whites and blacks who said "yes" was higher. But since 2003, the trend has been generally stable, with a little more than half of blacks saying yes, compared with between 15% and 20% of whites.

So there is no question that the nation has a racial divide in terms of the perception of the appropriate role of government in race relations. Blacks are much more likely than whites to want the government to play a major role in improving the social and economic position of blacks and other minorities, and more likely to believe that new civil rights laws are needed. Still, there is no universal consensus on this even within the black segment of the population, with a significant minority of blacks saying that the government should play only a minor or no role in improving the positions of minorities, and saying that new civil rights laws are not needed.

Neither question specified exactly what the government would do if it had a more major role in race relations, nor what the new civil rights laws would be. But the responses to the questions do reflect different views of government's role in this arena, and reflect the broad fundamental question of our times: What is the appropriate role of the government today in attempting to right wrongs; fix perceived problems; and change societal structures, systems, and culture in ways that are perceived to be in the interests of the greater good?