The term "social class" is commonly used in American culture today but is not well-defined or well-understood. Most of us have a sense of a hierarchy in society, from low to high, based on income, wealth, power, culture, behavior, heritage and prestige. The word "class" appended after terms such as "working," "ruling," "lower" and "upper" is a shorthand way to describe these hierarchical steps, but with generally vague conceptions of what those terms mean.

A focus on objective social class entails a direct determination of a person's social class based on socioeconomic variables -- mainly income, wealth, education and occupation. A second approach to social class, the one that occupies us here, deals with how people put themselves into categories. This is subjective social class -- an approach that has its difficulties but helps explain class from the perspective of the people. This is important since the way people define a situation has real consequences on its outcome.

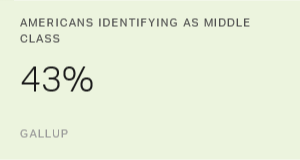

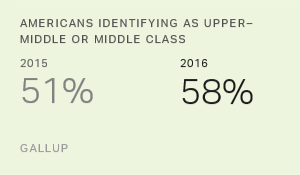

Gallup has, for a number of years, asked Americans to place themselves -- without any guidance -- into five social classes: upper, upper-middle, middle, working and lower. These five class labels are representative of the general approach used in popular language and by researchers. Gallup's last analysis showed that 3% of Americans identified themselves as upper class, 15% as upper-middle class, 43% as middle class, 30% as working class and 8% as lower class -- with noted changes in these self-categorizations over time.

What goes into determining the class into which Americans put themselves? We can't measure all possible variables theoretically related to class self-placement, including, in particular, family heritage and background, prestige of residential area, behavior relating to clothes, cars, houses, manners, spouses and family context. But, we can look at the statistical relationship between social class placement and a list of socioeconomic and demographic variables included in an aggregation of three Gallup surveys conducted in the fall of 2016. This analysis controls for all other variables, allowing us to pinpoint the independent impact of each variable on social class identification.

As we would expect, income is a powerful determinant of the social class into which people place themselves, as is, to a lesser degree, education. Age makes a difference, even controlling for income and education, as does region, race, whether a person is working, and one's urban, suburban, or rural residence.

Americans' political party identification, ideology, marital status and gender make no difference in how they define themselves, once the other variables are controlled for.

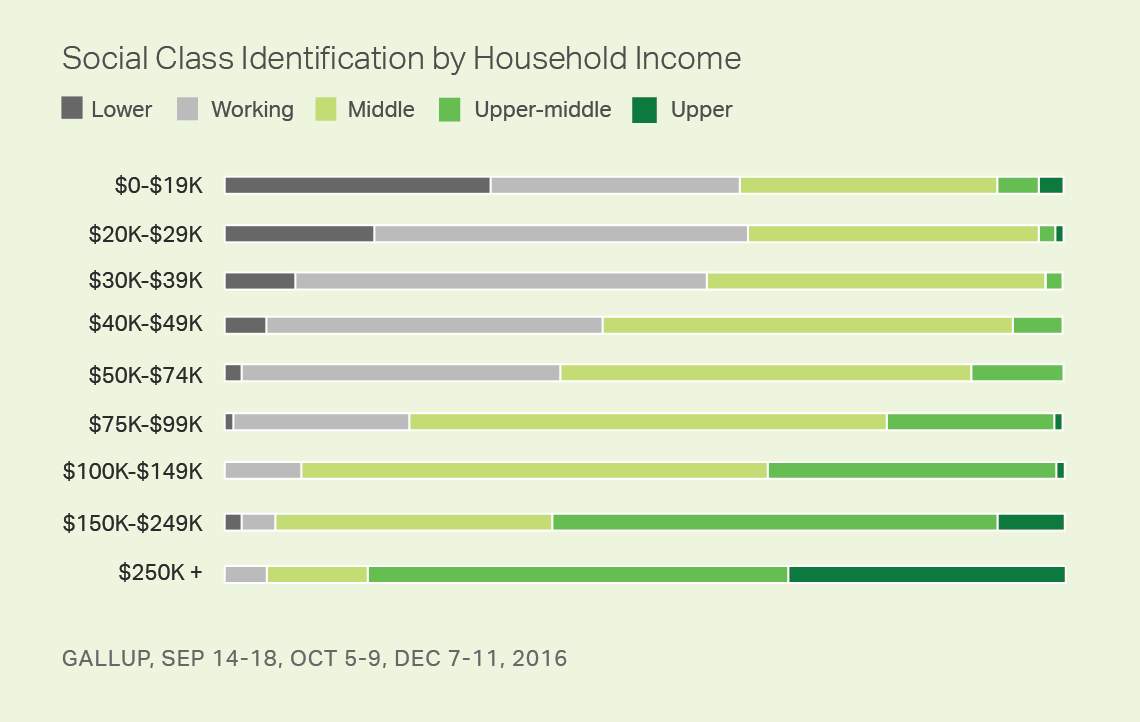

The accompanying graph displays the relationship between income and subjective social class. The statistical model we discussed above is based on the complex analysis of the totality of all of the variables at once; the data represented in the table are the simple display of social class identification at each income level.

-

At the lowest level of yearly household income included in this study (under $20,000 a year), people are equally likely to identify as "lower," "working" and "middle."

-

Identification as lower class drops rapidly as income increases, while identification as working and middle class increase. Among Americans with incomes between $30,000 and $40,000, for example, well below the median income for the U.S., less than 10% identify as lower class. Working class is modestly more prevalent than middle class.

-

We see a change at around $40,000; people at that level become more likely to say they are middle class and less likely to say they are working class.

-

Working class identification shrinks significantly at the $75,000-$99,000 yearly income level. Middle class still dominates, but upper-middle class becomes somewhat more predominant.

-

$150,000 is the income level at which upper-middle class becomes the most dominant social class identification -- with almost all of those who don't choose upper-middle class settling on middle class.

- Finally, a third of Americans making $250,000 a year and more, the highest broad group we represent in the graph, identify as upper class, with most of the rest as upper-middle. There are few people in our survey who say they make $500,000 a year or more, and of this small group -- not represented in the chart because of small sample sizes -- only about half say they are upper class. Most of the rest identify as upper-middle class.

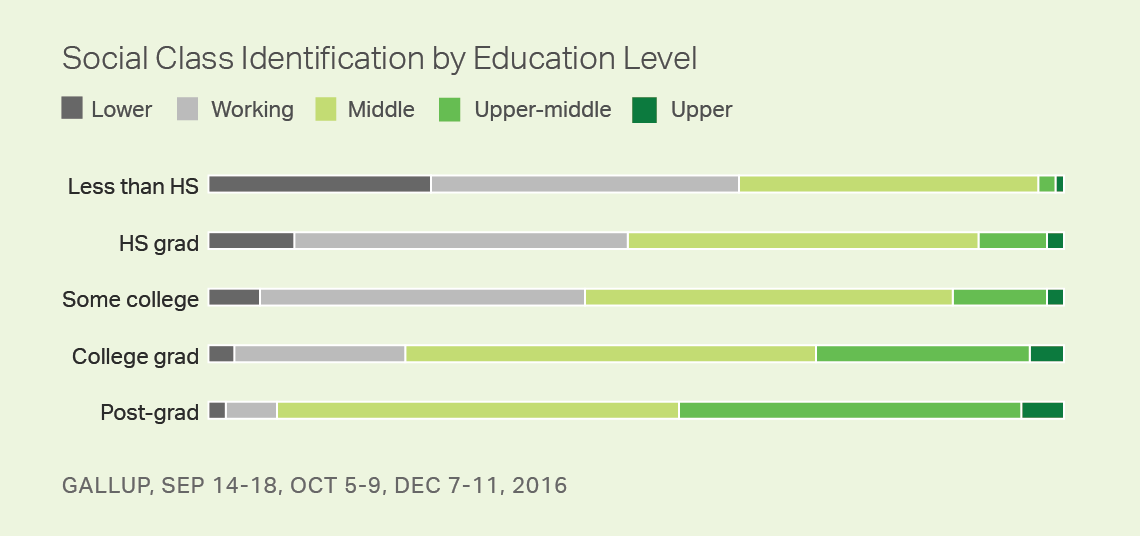

The biggest impact of education on subjective social class comes at the college graduate level, at which point working-class identification drops significantly, with a concomitant rise in identification as upper-middle class. Middle-class identification is surprisingly constant across all levels of education. Less than half identify as working class at any educational level.

The biggest impact of age comes among those who are 65 and older, who are more likely to identify with a higher social class compared with younger people.

There is an impact of race. Everything else being equal, whites are more likely than nonwhites to identify with a higher social class.

People living in rural areas are less likely to identify in a higher social class compared with those living in urban and suburban areas.

Final Thoughts

While in many minds there may be a lower class and an upper class in American society today, relatively few Americans at any income or education level like to think of themselves as being in those classes. Americans with very low socioeconomic status are just as likely to see themselves in the working or middle class as in the lower class, while Americans with very high socioeconomic status view themselves in the upper-middle class rather than the upper class.

The data support, to some degree, the popular conception of a dividing point at the college graduate level between those who are working class and those who are not. Still, less than 40% of Americans without a college degree identify as working class. For those with a high school degree or some college education, middle class edges out working class, while for those with less than high school education, the majority identify as either middle or lower class. In short, Americans' resonance with the label "working class" is not as substantial as might have been expected, even for those without college degrees.

The fact that political identity doesn't affect subjective social class is important, given the extraordinary importance of partisanship on so much else that shows up in our data. In other words, for people with the same socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, being a Democrat doesn't make one more likely than being a Republican to identify as working class. Nor does being a Republican make one more likely than being a Democrat to identify as upper-middle or upper class.