Story Highlights

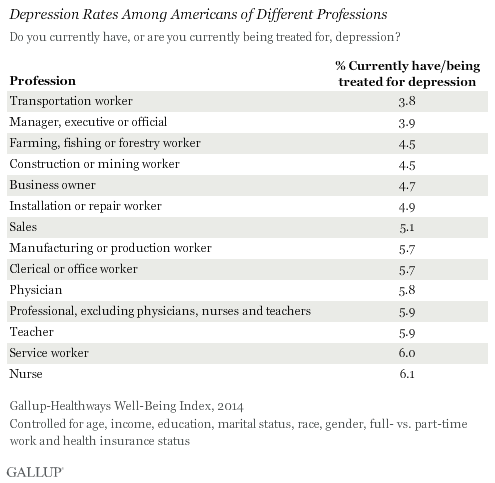

- Less than 4% of managers, transportation workers were depressed

- In 2014, 6.3% of service workers said they were currently depressed

- Less than 9% of managers have a history of depression

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- In 2014, 3.9% of managers and executives in the U.S. said they were currently suffering from depression -- nearly tied with transportation workers, but among the lowest of 14 occupation categories analyzed. By contrast, 6.0% of service workers and 5.9% of professional workers last year reported having or being treated for depression.

As part of the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index survey, Americans report whether they currently have or are being treated for depression, as well as whether they have ever been diagnosed as being depressed. Employed Americans also categorize the type of work they do in their primary jobs, which are then broken into 14 broad groups. Because factors such as income and gender have previously been found to have an impact on depression rates, these rates were controlled for age, income, education, marital status, race, gender, full- versus part-time work and health insurance status.

Gallup has recently been focusing on what it means to be a manager in the United States, underscoring the importance of the finding that managers are less likely to report being depressed than are office workers or professional workers, the people with whom managers work closely and often lead. The act of leading may contribute to a lower rate of depression among managers overall, compared with those not in managerial or leadership positions. Or, it may be that those who naturally act as leaders, and who are often then promoted to the role of manager, are people less likely to suffer from depression.

Professional workers -- the largest occupational category Gallup and Healthways analyzed -- join service workers as being significantly more likely to report having depression than the six groups least likely to be depressed, including managers/executives. Depression rates among nurses, physicians and teachers are similar to those found among professional workers and service workers. Transportation workers match managers/executives in their low depression rates, with less than 4% of each group reporting that they are currently being treated for depression. Regardless of occupational category, depression rates are low, with well over nine in 10 workers in every category saying they are not currently depressed or being treated for depression.

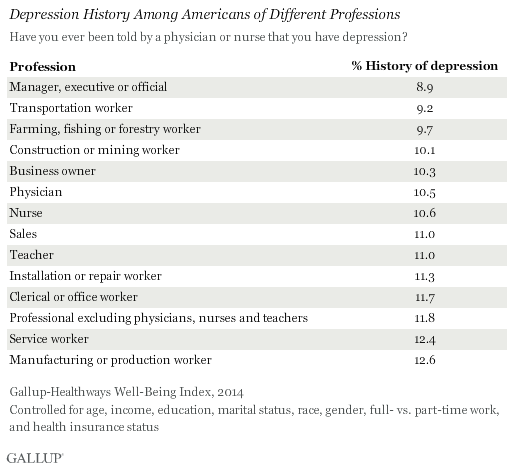

Less Than 9% of Managers Report History of Depression

Higher percentages of workers say that a physician or nurse at some point has told them they have depression than say that they are currently depressed. But, as was the case with current depression rates, managers score among the lowest on this history measure, and are the only profession in which less than 9% report a history of depression. This makes managers statistically less likely to have suffered from depression in their lifetime than nine of the 14 professions analyzed.

At least 12% of service workers and manufacturing workers report that they have been diagnosed with depression sometime in their lifetime. This makes them significantly more likely to have a history of depression than managers/executives, business owners, construction workers, transportation workers and farmers.

Overall, in data collected throughout 2014, 17.5% of Americans report having been diagnosed with depression at some point in their lifetime, and 10.4% currently have depression or are being treated for it. Previous Gallup research has found that unemployed Americans are more likely to suffer from depression than employed Americans, which helps explain higher depression rates among the general U.S. population than was found within these professions.

Bottom Line

Managers and executives are among the occupations least likely to suffer from depression in the U.S. In 2013, Gallup reported that depression was linked to higher rates of absenteeism, costing employers an estimated $23 billion in lost productivity each year, and depression is more prevalent among the long-term unemployed. Depression has also been linked to higher rates of heart attack. And the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that mental illnesses -- specifically, depression -- were associated with an increased prevalence of chronic diseases, which can cause Americans to leave the workforce.

Gallup and Healthways have previously found that managers have well-being index scores similar to those of professional workers. This indicates that managers don't have higher well-being overall than the professional workers they may be managing, but instead have some unique characteristics that help them avoid depression. Managers may benefit from their work roles, which often allow for more autonomy than other roles, and which could act as a barrier to depression for some. Or possibly the higher responsibility or power managers have could be associated with lower levels of depression. It may also be that the skills often necessary to rise to the level of manager -- self-assurance or leadership, for example -- make people who possess those traits less likely to be depressed.

Regardless of the cause, depression is a debilitating disease, and managers should work to lower depression rates among their employees in order to lower absenteeism and increase their employees' general well-being.

Survey Methods

Results are based on telephone interviews conducted Jan. 2-Dec. 30, 2014, as part of the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index survey, with a random sample of 73,639 adults, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. For results based on the total sample of Americans in each profession, the margin of sampling error ranges from ±0.6 to ±1.8 percentage points at the 95% confidence level. All reported margins of sampling error include computed design effects for weighting.

Each sample of national adults includes a minimum quota of 50% cellphone respondents and 50% landline respondents, with additional minimum quotas by time zone within region. Landline and cellular telephone numbers are selected using random-digit-dial methods.

Learn more about how the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index works.