Here are some questions that leaders often ask themselves: How can I fix my weaknesses to be a more complete leader? How can I emulate the traits of the great leaders who preceded me? What should I focus on -- vision or strategy? Here is the answer to all those questions: Don't bother.

Concentrating on those issues will only distract you from the most important aspect of leadership: your natural talents, which can be developed into strengths. According to Tom Rath and Barry Conchie, coauthors of Strengths Based Leadership: Great Leaders, Teams, and Why People Follow, strengths are what make leaders great.

We all have natural talents, of course, but the greatest leaders are highly aware of theirs. They know what they're good at and spend countless hours making themselves better at what they do best. They don't try to make themselves well-rounded or like some other leader. Nor do they devote their energies solely to the relentless pursuit of strategy, vision, or any other ideal. And what they don't do well, they hire someone else to do.

Rath, Conchie, and a team of Gallup researchers based those findings, and the book itself, on interviews with thousands of leaders and followers from organizations around the world. Unlike most books on leadership, Strengths Based Leadership doesn't assume anything about leadership; rather, the authors and their research team asked question after question, then sifted through the answers to find a common thread. And among the many findings that emerged, this one was the biggest: Great leaders are strengths-based leaders.

In the following interview, the second of two parts, Conchie and Rath talk about leadership strengths and how to identify and use them. They discuss the dangers of fixing weaknesses, mimicking other leaders, and focusing on any one aspect of leadership.

GMJ: Many people don't feel much affinity for their bosses, do they?

Tom Rath: On average, spending time with your boss is consistently rated as the least pleasurable activity in a given day. When you ask people about what they enjoy doing, time spent with the boss is even worse than time spent cleaning the house. So this suggests that there are a lot of leaders out there who are not doing an adequate job.

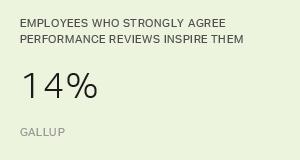

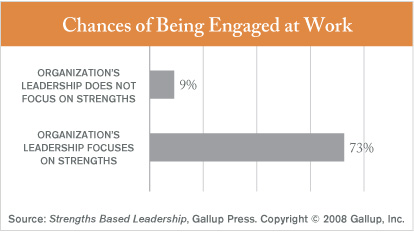

But in organizations with leadership that focuses on the strengths of their employees, the odds of people being engaged go up about eightfold, according to our research. So it's important that leaders focus on employee strengths because maybe the most critical part of their job is helping others uncover their strengths. That's not occurring as much as it should, and it's creating quite a bit of disengagement.

GMJ: Of the thirty-four talent themes that the Clifton StrengthsFinder assessment identifies, which are the most common among great leaders?

Barry Conchie: I've got a problem with the question.

GMJ: Why?

Conchie: There is no single characteristic or set of characteristics that would enable us to determine an effective leader. The most effective leaders are the ones who figure out how best to use what they've got. So it matters less what the strengths are in terms of the themes; what's key is that the leaders understand the strengths they have, how those strengths help them to be effective, and that they use strategies and methods to deploy their strengths to the greatest effect.

Rath: I think that from all the research that Gallup's done on leadership over the last three or four decades, the broadest discovery is that there is no universal set of talents that all leaders have in common. As we looked through these data and ran through hundreds of transcripts and individual interviews, we were struck by just how different all these leaders are.

If you were to sit down with each of the four leaders we featured in the book [Brad Anderson, vice chairman and CEO of Best Buy; Wendy Kopp, CEO and founder of Teach For America; Simon Cooper, president and CEO, The Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company, LLC; and Mervyn Davies, chairman, Standard Chartered Bank], you'd notice that they do things very differently based on their strong awareness of their unique talents.

GMJ: You wrote: "If you spend your life trying to be good at everything, you will never be great at anything. While our society encourages us to be well-rounded, this approach inadvertently breeds mediocrity." Why is that?

Conchie: The great leaders we've studied are not well-rounded individuals. They have not become world-class leaders by being average or above-average in different aspects of leadership. They've become world-class in a relatively limited number of areas of leadership. They've recognized not only their strengths but their deficiencies, and they've successfully identified others who compensate for those deficiencies.

Leaders who really understand their strengths find their way of leading. Mimicry takes away from who you naturally are.

The concept of well-roundedness is illusory. It might sound desirable from a developmental perspective, but really all that happens when people try to fix their weaknesses is that they spend inordinate amounts of time trying to become marginally better in an area that will never be particularly strong for them. So they'll get far less of a return by trying to shore up relatively mediocre capabilities because they'll probably always be below average in those areas. Leadership is not a construct of well-rounded attributes; it's nearly always the consequence of some pretty incisive talents that are relatively specific and slightly narrow in focus being leveraged to the maximum.

Rath: The leaders we've studied and interviewed have spent tens of thousands of hours leveraging their natural talents, practicing and adding knowledge and skills to that base. They aren't just naturally gifted. We've found that a lot of talent with little effort is about as useless as a lot of effort with little talent. Either one without the other is a waste. You need a lot of effort and talent to produce greatness.

GMJ: What happens to leaders when they try to mimic great leaders? Can you really be Winston Churchill in seven days by following a simple formula?

Rath: No. I suppose that gets back to the point of well-roundedness; if a leader doesn't have a basic awareness of her natural talents and where she could have the most return on the time she invests, it's very unlikely she'll go far by trying to be a little bit like five or ten great historical leaders. And as we discussed in the book, when you look at some of the best leaders throughout history, they've all done things differently. So if you try to follow someone else's style, you'll essentially achieve mediocrity.

Conchie: Leaders have got to lead without pretense. Leaders who really understand their strengths find their way of leading. Mimicry takes away from who you naturally are. So unless there is a perfect overlap of styles, which is extremely unusual, leaders will always be less genuine when they mimic others.

GMJ: Can anyone become a leader?

Rath: Well, in our poll, about ninety-seven out of a hundred people think that their ability to lead is at or above average. So there are certainly a lot of people who aspire to lead.

Conchie: I feel there are two issues here. If you're looking at leadership as a consequence of career progression and position, then statistically, fewer individuals by definition have the opportunity to become a CEO, for example, than to lead a group of salespeople. But if you look at leadership not as a position but as an attitude and a capacity to influence others, then there is far more leadership in the world than we probably think. Many people can exercise leadership if you help them understand how to do it. It's far less exclusionary to think of leadership in those terms.

GMJ: What's more important for effective leadership -- developing people or developing strategies?

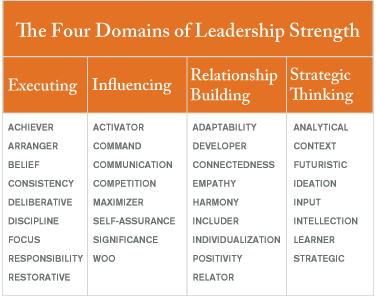

Conchie: They're both very important. And you also need the ability to influence people and the ability to execute. So I don't think it's a case of either/or. We have discovered from our research that there are four domains of leadership strength -- executing, influencing, relationship building, and strategic thinking -- and all are critical to the overall effective functioning of a leadership group. You need to make sure that there's sufficient strength and capability within a team to cover those different domains of leadership. Any individual domain becomes accentuated when it's lacking. So to rephrase your question: What's more important, strategic thinking or relationship building? Well, if one or the other is relatively weak within the team, then that domain becomes more important, because you need to compensate for it if the team is to be successful.

Rath: There's a conventional wisdom that says that strategic thinking is much more important than relationship building, which doesn't seem to be nearly as highly valued as it should be, based on what some of the leaders that I've spoken with have said to me. But relationship building and strategic thinking are very important in bringing a team together to achieve a big goal. If you only have strategic thinking, you'll head in the right direction with no one behind you. If you have relationship building without strategic thinking, you have a really happy team that might not be headed toward a result.

-- Interviewed by Jennifer Robison