We all know that negativity is harmful. But did you know it costs the U.S. economy an estimated $300 billion a year? Or that the effects of intra-office negativity can scare away customers? In contrast, businesses that encourage positive personal interactions can gain a lucrative advantage over their more negative rivals.

Organizational positivity may seem like a new concept, but ideas on it have been churning for some time. A half-century before he was cited as the "Father of Strengths-Based Psychology" in an American Psychological Association Presidential Commendation, Donald O. Clifton, Ph.D., was studying the effects of positivity on people and organizations. His research led him to believe that positive human interactions had a vastly greater effect than anyone had ever realized.

To explain his insights, Dr. Clifton created the Theory of the Dipper and the Bucket. To put it simply, we all have a metaphorical bucket. The bucket is filled by positive interactions and emptied by negative ones. We feel great when our buckets are full, rotten when they aren't. We also have a metaphorical dipper that we can use to empty or fill other people's buckets -- but when we fill others' buckets, we also fill our own. Thus, an organization populated by people with "full buckets" would have much more positive energy than one of people with "empty buckets" -- and would be more productive and profitable.

|

The analogy developed a life of its own. Eventually, 5,000 organizations and more than 1 million people put the Theory of the Dipper and the Bucket into practice. By the late 1990s, mountains of hard science had accumulated that proved the theory was correct. People all over the world were asking Dr. Clifton to write a book describing the research behind the theory and suggesting practical ideas for using it.

In 2002, Dr. Clifton was diagnosed with a particularly aggressive form of cancer. He knew his time was growing short, and he spent his last few months working on the book that so many people had requested. Dr. Clifton asked Tom Rath, The Gallup Organization's global practice leader in strengths-based development -- and Dr. Clifton's grandson -- to help. They finished the book shortly before Dr. Clifton died, and the fruit of their collaboration, How Full Is Your Bucket? Positive Strategies for Work and Life, was released this month by Gallup Press.

In the following conversation, Rath explains what negativity actually costs American businesses and describes the right and wrong ways to recognize employees' good work.

GMJ: When you say "fill someone's bucket" or "empty someone's bucket," you're speaking metaphorically. What do you mean literally?

Tom Rath: I'm talking about the momentary interactions we have with people every day. These interactions can be positive, negative, or neutral. One of Gallup's senior scientists, Daniel Kahneman, suggests there are approximately twenty thousand moments in a given day, and each one lasts about three seconds. [ Winner of the 2002 Nobel Prize in economic sciences, Dr. Kahneman is Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology and professor of public affairs in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University. -Ed.] In our book, we point out that those three-second interactions are rarely neutral; they're almost always positive or negative. And we can deliberately choose to make them positive or negative.

GMJ: So what does this theory have to do with the workplace?

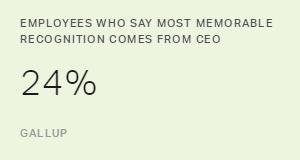

Rath: Our relationships with people are formed by small moments -- and relationships are crucial in business. Data from the U.S. Department of Labor show that the main reason people leave their jobs is because they don't feel appreciated. A Gallup Poll shows that in the last year, 65% of people received no recognition for good work in their workplaces. So clearly, there aren't enough positive moments or interactions happening in the workplace. As a result, our economy suffers, companies suffer, and individual relationships suffer.

GMJ: What's the financial aspect of positivity?

Rath: Gallup polling has revealed that 99 out of 100 people say they want a more positive environment at work, and 9 out of 10 say they're more productive when they're around positive people. Employees who report receiving recognition and praise within the last seven days show increased productivity, get higher scores from customers, and have better safety records. They're just more engaged at work.

On the other hand, people who are actively disengaged -- employees who are not only unhappy with their own roles, but are also scaring customers off -- cost the economy between $250 billion and $300 billion a year. And when we add injury, illness, turnover, and other factors associated with negativity or active disengagement, the cost could be closer to a trillion dollars, and that's nearly 10% of the U.S. GDP.

GMJ: Let's say you want to boost positivity in your workplace. How do you do it?

Rath: Wanting a more positive environment isn't enough. You need to do something, and it doesn't require a great deal of effort or some huge change in the way you approach things at work. It really just requires a little bit more concentration in the moment, and I think you can start with a few building blocks and go from there.

GMJ: What would those building blocks be for managers?

Rath: Well, don't overwhelm people with positive emotion in the workplace by cutting out negative emotion. Ignoring negative things that need to be changed is destructive and does nothing to alleviate negativity. Instead, we should focus on the way we're treating other people in our brief interactions with them.

Barbara Frederickson [Director of the Positive Emotions and Psychophysiology Laboratory at the University of Michigan] and Marcial Losada [Professor of Complexity Sciences at Universidade Católica de Brasília] have been looking at scoring positive exchanges. They've discovered a 3:1 ratio. When a work team has more than three positive interactions for every one negative interaction, it is significantly more likely to be productive. When the team is below that line, it's significantly less likely to be productive.

GMJ: When I was in junior high, our principal would stand in the hallway and clap at us all day. "Go team!" over and over. I'm sure he was trying to increase positivity, but it was weird and annoying.

Rath: That would be downright annoying. I would absolutely recommend against excessive positivity and optimism. Any positive emotion that you're infusing into a workplace needs to be grounded in reality. If it's not realistic, sincere, meaningful, and individualized, it won't do much good. Telling someone "great job" is not specific. Saying "great job" and "here's exactly why I appreciate your work" takes it to an entirely different level. Not only does this fill their bucket a little more, it makes them more likely to repeat that behavior.

GMJ: Does recognition received in front of the whole company do more to fill a bucket than just a kind word from the boss?

Rath: It varies from person to person. Public recognition will motivate some people but not others. That's why the best recognition is tailored to the person who's receiving it.

I think anyone who manages another human being or is responsible for recognition programs needs to ask questions. Recognition is a very, very personal thing. Some people want their name in lights, and others just want a quick pat on the back. Much of the recognition that's given at a big ceremony or awards show is not as individualized as it could be, and it's often misguided.

GMJ: Your book is really tough on Employee of the Month programs. Why?

Rath: Often, these programs start with the best of intentions. Someone in charge wants to promote more recognition in the workplace, so he starts a monthly recognition program. In the first few months, a few people who deserve recognition get it -- and even though it's not individualized, it might seem helpful. Eventually, however, the list of employees who really deserve recognition ends, and management has to figure out what to do next. So the manager puts someone's picture on the wall, giving recognition to an employee who doesn't deserve it. Instead, it was just his or her turn. This kind of recognition doesn't fill anybody's bucket.

Some of the better recognition programs I've seen include awards developed for different roles -- specific awards created just for the person and the task they've accomplished. Usually, the more variation, the more individualization.

GMJ: How should a manager handle an unpleasant conversation with someone without emptying his or her bucket?

Rath: I think it's most effective to focus on the outcome. Often, when a negative topic needs to be addressed in the workplace, the discussion gets personal -- it's all about an employee's attitude, what she should do, what she's done wrong. It just gets ugly at an emotional level, when it could have been a more positive conversation.

Another problem is that a lot of performance reviews focus on an employee's "areas for improvement" or "things you need to fix." Managers who start the conversation by focusing on a few good things that the employee has accomplished, then moving on to areas that need improvement, set up a more positive framework.

GMJ: What impact do managers really have on workers' positivity?

Rath: A huge impact -- usually for the good, but not always. In the book, we covered a study done in the United Kingdom about what I like to call "boss-induced hypertension." The researchers found that people who harbored real dislike for their bosses over long periods of time increased their risk of heart disease and stroke by one-third.

GMJ: So when you come home and say to your spouse, "My boss is going to be the death of me" . . .

Rath: That actually might be true.

-- Interviewed by Jennifer Robison