Last November, Gallup found that only 15% of Americans had "a great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in the U.S. banking system. That's a new low. This is a problem not only for the financial industry generally but for individual banks too. That's because people who lack confidence in their bank may be less loyal -- and they may be more likely to leave it and go elsewhere.

One of the worst things a company can do is to begin charging a new fee for a service that had previously been free.

Bankers may think they aren't doing anything wrong; they're just trying to provide a return for shareholders. So from their perspective, they're doing the right things. In that case, why are customers reacting so strongly? Because bankers are also doing things like overtly passing on costs in the form of fees, which infuriates the customers who are expected to pay them. And bankers are also making cuts in customer service, which not only angers customers, but it basically encourages them to walk out the door.

It doesn't have to be this way. As Gallup Chief Economist Dennis Jacobe, Ph.D., discusses in the following conversation, there are ways to do the right thing, both by the bank's P&L sheet and by its customers. But banks need a more educated view of customers and their own place in the consumer economy. In short, Jacobe says, they need to "think behavioral economics."

GMJ: What do you mean when you say banks should think behavioral economics?

Dennis Jacobe, Ph.D.: Behavioral economics is the study of the ways that emotion affects how people make decisions and, ultimately, how they behave. I think the debit card fee debacle provides a good example of how emotions play a role in consumer decisions.

The Dodd-Frank Act required changes in how much banks charged for processing debit card use. When the Fed issued the standards required by the act, bank management tended to feel that the imposition of limits on the fees they could charge retailers for debit transactions were totally unfair. As a result, many banks seemed to think it was OK for them to replace this source of income by adding debit fees to their customers' accounts. If they were questioned by their customers, they could explain that this was the result of a change in government policy. Thus, the debit fee pricing decision was a financial calculation aimed at replacing what had previously been a revenue source.

Unfortunately, this finance-focused approach to replacing the bank's lost revenue ignored some of the basic tenets of behavioral economics. From a behavioral economics perspective, one of the worst things a company can do is to begin charging a new fee for a service that had previously been free.

GMJ: And we all remember what happened.

Dr. Jacobe: Yes. Predictably, there was a huge backlash. And the situation was worsened by the way the proposed consumer debit fees became entangled with the anti-bank story line. Not only were these fees perceived as unfair, but they were also perceived as a way for greedy bankers -- who had been bailed out by U.S. taxpayers -- to gouge their customers. Further, the price-leader way of introducing these fees doomed them to failure.

GMJ: Price leader?

Dr. Jacobe: This is a tactic we often see in the airline industry: One airline announces a fee increase hoping the others will follow and match it. In this case, when some banks announced a debit fee increase, others did not follow the leader. As a result, it's not surprising that the banks that were trying to increase debit fees felt forced to rescind them before they went into effect.

This is all too reminiscent of banker efforts to charge for teller transactions many years ago. A terrible customer backlash led management to forgo teller use charges. However, it led to different forms of product packaging, which is a behavioral economics approach: Some banks offered a variety of discounts for not using the bank teller. In that instance, a behavioral economics approach changed a lose-lose scenario to a win-win.

GMJ: But most banks have shareholders. Don't those shareholders expect banks to make up the lost revenue?

Dr. Jacobe: Of course, and banks have approached this in various ways. Many banks have instituted new fee structures and/or cut services. Generally, they have suffered significant customer defections and a loss of loyalty and engagement among those customers who remain. These changes in the bank operating model -- and in combination with the overall decline in Americans' confidence in the nation's banks -- may explain at least in part why bank loyalty fell sharply as 2011 came to a close.

Given the current regulatory outlook -- and the recess appointment of Richard Cordray as the first head of the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau -- it seems likely that the bank operating model will continue to change and evolve in the months and years ahead. Instead of making product and service adjustments in the traditional finance-driven way, bank management would be well-advised to make these changes in a customer-centric way -- and in a way that reflects behavioral economics.

GMJ: You mentioned customer engagement. How can banks promote customer engagement when consumers may be wary of the banking industry overall right now?

Dr. Jacobe: That's another area that needs some behavioral economics application. Given the changing banking model, some banks have reacted by cutting back on employees. That may make financial sense in the short term. The fewer people on the payroll, the lower the operating costs, and cost cutting is required when revenues are declining.

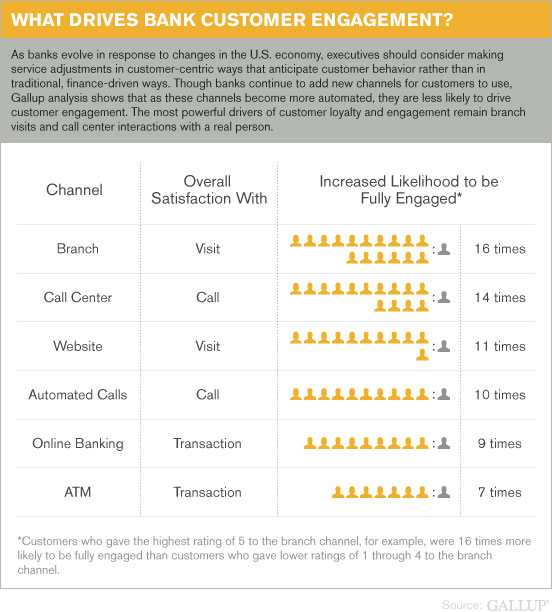

But that short-term gain -- and precisely how it is achieved -- needs to be viewed in a behavioral economics context, because customer-facing employees remain consumers' most preferred provider of banking services and may be a bank's best hope for promoting customer engagement. Gallup's 2011 proprietary retail banking study showed that the most powerful drivers of customer loyalty and engagement remain branch visits and call center interactions with a real person. So the last place to cut should be front-line employees, because when fewer people are providing what matters most to customers, loyalty and engagement can easily take a significant hit.

GMJ: Give me an example.

Dr. Jacobe: Cut back on people too much, and customers get longer times in the branches and on the phone. If you have fewer people to serve your customers, if you don't spend the money training tellers and bankers, then you don't have enough people providing top-quality customer service. Worse yet, a dehumanized approach to customer service can play right into the story line of greedy bankers who don't care about their customers.

GMJ: So banks can't assume that their websites can make up the difference in customer service.

Dr. Jacobe: Gallup's research shows that Internet and automated channels aren't the same. Customers use them, and they have a significant place in building relationships, but they can't replace human interaction. This may be disappointing to companies that have invested a lot of time and money in new technology assuming it would take care of most customer needs and cut employee costs.

According to the study, though online and automated banking channels are important to relationship building, they have become table stakes in building customer relationships. Banking consumers continue to use new channels while showing little tendency to substitute for -- or abandon -- live interactions through traditional branch and phone channels. Of course, this doesn't mean things won't change over time, but this is the situation bank management faces today.

GMJ: Which means that employees are still important in building customer engagement.

Dr. Jacobe: Employee engagement is more important today than at any time since the Great Depression because of lack of confidence in the banking industry and the declining confidence in individual banking companies. Most Americans don't seem to fully recognize the vital role our banking system plays in the success of the U.S. economy. Fully engaged bank employees can be important advocates for banking and their institutions by explaining to consumers and small-business owners alike not only the key role banking fills but also why banking needs as many advocates as possible right now.

GMJ: How does behavioral economics jibe with customer engagement?

Dr. Jacobe: That 2011 banking study also shows that individual banking companies have been able to significantly differentiate their customer engagement and loyalty over the past several years. Customer engagement is built on a hierarchy of responses, and the bare minimum of them is that the company executes and fulfills basic expectations. Banks that are too short-staffed don't have the people to do what banks are expected to do and keep wait times short, thus failing to meet customers' transactional requirements.

GMJ: How can banks engage their customers?

Dr. Jacobe: Customers become engaged only when four emotional needs are met: they feel pride and passion for the brand they bank with, they believe the bank has integrity, and they're confident they'll always be treated well and fairly. It's financially imperative that banks provoke this response. Fully engaged retail banking customers are much more likely to say they intend to open a new account or take out a new loan over the next three months than are actively disengaged customers. And actively disengaged customers are much more likely to switch banks.

It's very difficult to emotionally engage people who are irritated by being kept in line for a long time. And the customer-facing staff knows it -- they are quite capable of looking over the counter and seeing lines of impatient, angry customers. When that happens, bank employees can be forgiven for losing some of their own engagement, which has costs of its own. Disengaged bank employees are not good brand or banking ambassadors. They're brand killers. Banks need employees who are positive about their banking institution and positive about the role banking plays in making the economy function.

GMJ: What's your outlook for banking in 2012?

Dr. Jacobe: U.S. banks face a hostile environment in 2012. The European banking situation is likely to continue to remain volatile and unresolved. The U.S. economy is likely to continue to struggle. Most importantly, the intense political environment of the 2012 presidential election is likely to increase the demonization of the nation's banks -- and the regulatory activity of the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau -- while ignoring the vital role banking plays in the U.S. and global economy.

I think it is important that bank management recognize all aspects of this operating environment -- including Americans' perception of the banking business -- as they make their strategic decisions in the year ahead. They need to recognize that their business decisions can become political issues and act accordingly. Most importantly, they need to think behavioral economics.

-- Interviewed by Jennifer Robison