Neuromarketing is a concept based on fact plus a lot of assumptions -- and surrounded by a little fear. The fact is that the human brain responds to images and words, which is why advertising works. The assumption is that marketers, by using high-tech neurological equipment such as fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) machines that trace brain activity, could create more successful ads. The fear is that use of that knowledge could do more than stoke interest in a product -- it could more or less compel interest.

|

But does neuromarketing even work? And is it ethical? Maybe and maybe not, says John Fleming, Ph.D., a Gallup principal and chief scientist for customer engagement and HumanSigma -- a management approach that helps organizations boost financial performance by assessing, managing, and improving the employee-customer encounter.

So what was Dr. Fleming doing in Tokyo last year, standing over an fMRI machine collecting brain scans of 16 of that city's shoppers? Dr. Fleming is also one of a team of scientists who researched and developed CE11, Gallup's metric of customer engagement, which differentiates between consumers' deep emotional attachment and mere satisfaction. Boosting profitability by increasing emotional response sounds a lot like neuromarketing, right? According to Dr. Fleming, it's not. And in this interview, he discusses his take on neuromarketing, explains how increasing positive emotion is both profitable and ethical, and tells what he discovered in Tokyo.

GMJ: What's your take on neuromarketing?

Dr. Fleming: It's really an area that is in its infancy, and it has attracted both strong proponents and big critics. Within the academic community, the scuttlebutt that I've heard from neuroscientists is that neuromarketing runs the risk of being perceived as a sham science. It's being criticized on those grounds.

GMJ: Why?

Fleming: I'm not sure that anyone has conclusively demonstrated that neuromarketing works, and many neuroscientists doubt it can. But that sidesteps the ethical considerations. Regardless of whether it works or not, there's a fear that it could. There's a kind of Big Brother, 1984, scary aspect to it. The basic premise is that there are neurological triggers that marketers can use to further embed their brand, and the frightening dimension is that the targets don't know they're being targeted and manipulated. So the idea that marketers could get access to information about what makes things happen in your brain and manipulate you without your knowledge is scary to a lot of folks. Has it been done? I don't think it has. Could it be? It's conceivable.

GMJ: But isn't marketing itself a configuration of words and images meant to embed brands? Isn't that the whole idea?

Fleming: Yes, but it's always been assumed that there was some sort of thoughtful mediation or reflection involved. There are people who believe that, for example, Ronald Reagan got elected because he was very clever in his use of the American flag in every one of his ads and those images somehow connected him with American values. But no one would argue that the flags drove anyone to vote for Reagan; they just provided a strong image. So, there are people who say that neuromarketing is merely another extension of what we've been trying to do all along, which is get inside the heads of people.

|

The pushback is that words and images have never been shown to actually produce organic changes in the brain, which is the goal of neuromarketing. There has been a belief, however unfounded, that marketing involved some kind of thoughtful mediation between advertisers and consumers: The target actually had to think about the ad or the product, at least a little bit, then do something. But the specter raised with neuromarketing is the possibility that what marketers know about the things that can change a consumer's brain gives them an inside advantage that the consumer can't counter.

GMJ: So with neuromarketing, marketers are basically trying to find a way to ring the bell that makes Pavlov's dog salivate.

Fleming: Right, exactly -- but without doing all the conditioning usually required to elicit a response. Our intent with the Tokyo study, in contrast, was to go in a totally different direction. We didn't want to join the fray of neuromarketing. Instead, we wanted to demonstrate that creating certain conditions -- beliefs or feelings or emotions -- causes, or at least is related to, people thinking differently about a product and a company. And we wanted to understand the link between those conditions and future behavior. We weren't interested in using this understanding for the same purposes as neuromarketers. We were trying to validate a set of attitude measures that could be used to proactively manage a business.

|

GMJ: So tell me about the Tokyo study.

Fleming: First, six to eight weeks before the experiment, we recruited customers from the general Tokyo metropolitan area who shopped at an upscale retailer in Tokyo. We interviewed some four hundred people, and our goal was to identify three different groups of customers: a group of highly engaged customers, a group that was less engaged, and a group that was essentially neutral to negative. In the end, we studied sixteen women. We chose women for this study because there are demonstrated differences in brain structure between men and women, and when you mix genders, you introduce a source of bias into the results.

Then we asked the participants to come to the lab and lie inside an fMRI machine, and we scanned their brains as they responded to a series of questions. We asked the CE11 metric questions about the retailer plus some other related questions, a similar set of questions about their bank, and questions about their everyday life -- the last two sets were the control questions. What we wanted to know was whether higher levels of engagement with the retailer were related to different levels of processing activity in certain specific parts of the brain related to emotion. (See sidebar "L3 + A8 = CE11: Questions That Get at the Heart of Customer Engagement.")

GMJ: And what did you find?

Fleming: Well, we found that the higher the level of engagement, the more activity occurred in three specific areas of the brain: the orbitalfrontal cortex, which is where emotion and cognition are integrated; the temporal pole, which is one area for accessing memory; and interestingly, the fusiform gyrus, which is implicated in facial recognition. So, the initial hypothesis was that the more engaged customers are, the more actively they pull out memories -- and that their thinking process involves faces. The hypothesis was that they were probably recollecting an experience they'd had at the retailer, and at the same time, they were more active in integrating emotional and cognitive information.

|

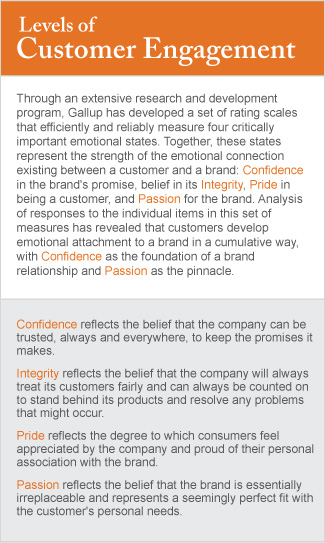

Now that was the result for the overall measure of customer engagement. When we looked more closely at those who scored high on questions related to their "Passion" for the retailer, two additional areas of the brain lit up. [See sidebar "Levels of Customer Engagement."] The first was the amygdala, which is the area associated with emotional processing. The second area was the anterior cingulate gyrus, which is implicated in binary decisions -- for example, decisions about what is good or bad. So those customers who had intensely strong feelings of attachment to the retailer also showed enhanced activity in the amygdala, which is the emotional storehouse, as well as the area involved in good/bad decision making. The implication is that their brains were firing off on a lot of emotional content.

GMJ: So the parts of the brain that activate when you're remembering a person you love also light up when you're thinking about a brand you love? In other words, to the amygdala, love is love, whether it's love for a spouse or a brand of toothpaste. That's pretty powerful. Is that why you were interested?

Fleming: Well, this research was important to us because, with its CE11 metric, Gallup makes the claim that emotion mediates the relationship between a customer and a company, and that emotion mediates that customer's ultimate behavior. So it's important to show that emotion at an organic level is involved and not just something else.

Now here's the important point: When we looked at customer responses to the three CE11 questions that measure traditional indicators of attitudinal loyalty -- I intend to purchase or visit again, I would recommend, and I'm satisfied -- we didn't find any enhanced brain activity, no matter how loyal or disloyal the customer might have been. But we saw a lot of brain activity associated with the eight CE11 questions that measure emotional, rather than cognitive, attachment. In other words, we saw engagement rather than satisfaction.

GMJ: That's a reversal, considering how much money businesses pour into customer satisfaction measures.

Fleming: People have always assumed that satisfaction was the right measure. They assume that measures of "employee satisfaction" work, and they assume that measures of "customer satisfaction" work too. No one bothered to step back and ask, "Are we asking the right questions?" No one questioned the link between the question and the behavior. When we began delving into the link between the question and the behavior, we found that satisfaction didn't do a very good job of predicting how people actually behaved.

|

So how do we know now that we're asking the right questions? Well, we know we're asking the right questions because at an aggregate level, the questions relate to actual behavior. And we've demonstrated that result hundreds of times in our data, but now we can actually see those results happen in the brain. The importance of this study is that it allows us to show an organic effect that mediates the engagement measures we collect. And this is important, because we collect these measures in advance of financial performance measures. Emotional engagement measures are leading indicators of consumer behavior that companies hope to influence in the future.

GMJ: What do you mean by "leading indicators"?

Fleming: Let me ask you a question. How do you know if a company is successful?

GMJ: If its revenue is healthy, if it's increasing employment, or if its share price is going up.

Fleming: That's what most people would say. But think about it for a moment. Those measures show that your company is succeeding after the fact, right? Those indicators show that your company has been successful, but not that it still is or will be. A leading indicator is useful because it allows corporate leaders to anticipate the need for change before it shows up in outcomes that can't be changed. You can't steer the car by looking in the rearview mirror.

Today, we may look at our corporate balance sheet and decide our company is healthy, but we have no idea whether it's going to stay that way in the future. The outcomes that business cares about are revenue, growth, and profitability. So the search began for things that would serve as an early-warning system to tell us if our company's health was in jeopardy long before it ever showed up on the balance sheet.

What the CE11 metric does is give businesses that forward look. What the Tokyo study does is show how that forward look works. Engagement is that forward look, because engagement triggers customer behavior that's positive toward the brand. Now in the Tokyo study, there was a very strong relationship between our measure of attachment and actual spending (a correlation of about .6 on a scale of 0 to 1). What that says is the higher the score on attachment, the more they spend.

GMJ: How does a business increase that attachment, that engagement?

Fleming: You first have to understand that attachment is an emotional connection. Then you need to begin to identify activities that drive that emotional connection. And though those activities will be unique for every business model within an industry, those levers can be determined statistically.

One of the most potent levers is the interaction that customers have with your staff. So help your employees understand how to maximize the emotional benefits they can deliver each and every time they interact with a customer -- it's a powerful creator of value. [See "Marketers: Don't Ignore Your Company's Employees" and "Living the Brand" in the "See Also" area on this page.]

A lot of customer service training has been about execution, steps, behaviors, transacting. It needs to evolve to a new platform, one that says the transaction and the execution are the minimal acceptable outcomes and that the customer actually expects more than simply transactions. That's a first step. Another way to improve is to go into your organization and identify those locations where that engagement is already happening. Use them as a source of solutions for the rest of the company.

GMJ: So every company already has a blueprint; they just have to look for it.

Fleming: That's exactly right. But here's the key: Up until a few years ago, business leaders made the assumption that certain leading indicators were valid, notably employee satisfaction and customer satisfaction. They didn't really bother to check whether high performance on this or that indicator was actually related to future good performance on the things they cared about -- growth, revenue, and profitability. But it turns out that customer satisfaction is the low bar of performance. Satisfied customers don't stay with companies; they aren't more profitable, and they don't deliver value to the company.

The difference between satisfaction and engagement is that engagement includes an understanding of the crucial emotional connection that ultimately drives customer behavior. And we know that it drives customer behavior because we've done the linkage work that proves that the more engaged a customer is, the more value he or she delivers to a company. Engaged customers deliver increased purchasing, increased share of wallet, higher levels of profitability, deeper cross-sell, willingness to try different options, new products, and importantly, a reduced cost to service. I saw all that happen in someone's brain, and I'll tell you, it's a powerful thing to see.

|

L3 + A8 = CE11: CE11 measures three key factors pertaining to a customer's rational assessment of a brand (L3) but also adds eight questions on emotional attachment (A8). L3 • Overall, how satisfied are you with [Brand]? • How likely are you to continue to choose/repurchase/repeat (if needed) [Brand]? • How likely are you to recommend [Brand] to a friend/associate? A8 CONFIDENCE • [Brand] is a name I can always trust. • [Brand] always delivers on what they promise. INTEGRITY • [Brand] always treats me fairly. • If a problem arises, I can always count on [Brand] to reach a fair and satisfactory resolution. PRIDE • I feel proud to be a [Brand] [customer/shopper/user/owner]. • [Brand] always treats me with respect. PASSION • [Brand] is the perfect [company/product/brand/store] for people like me. • I can't imagine a world without [Brand]. Copyright © 1994-2000 The Gallup Organization, Princeton, NJ. All rights reserved. |

-- Interviewed by Jennifer Robison