If higher education was the auto industry, it would be forced to recall a quarter of all its graduates.

Ninety-six percent of Americans say it is "somewhat" or "very" important for adults in the country to have a degree or certificate beyond high school. Clearly, the perceived importance of postsecondary education remains very high, especially considering the majority of American adults do not have a degree. But something very troubling lurks beneath the surface of this finding in the recently released fourth annual Gallup-Lumina Foundation poll.

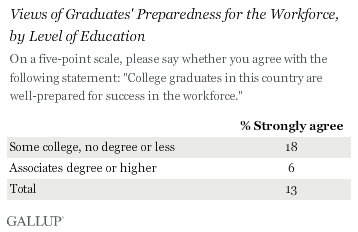

Only 13% of Americans strongly agree college graduates in this country are well-prepared for success in the workplace. That's down from 14% two years ago and 19% three years ago. This is effectively a "no confidence" vote in college graduates' work readiness, and if we don't work to fix it, there will be catastrophic effects for the American education system and economy.

The no confidence vote gets worse: Americans with college degrees are much less likely to strongly agree college grads are ready for the workforce than Americans without college degrees -- 6% vs. 18%, respectively.

To be clear: Those of us who earned a coveted college degree have even less confidence than the rest of us that college grads are well-prepared for success in the workplace. "Unnerving" is the only word that comes to mind regarding this finding. Why? Because no matter whom you ask -- the general population of Americans, parents of fifth- to 12th-graders or current college freshmen -- they all give the same answer to their top reason for valuing or attending college: to get a good job. Their goal is not simply to get a degree, but rather it's to get a good job. The outcome is a job, and the degree is just a means to it.

It's great that we still have an overall belief in the value of postsecondary education, but if we don't have confidence that college graduates are prepared for the outcome (e.g., a good job) of a degree we value most, a lot of things start to unravel. Americans stop valuing postsecondary education. Then they stop leveraging themselves financially to attend. Then they start looking for other paths to a good job -- some of which may end up being fruitful (like trade apprenticeships or starting their own business) -- but many of which will be disastrous (trying to become an accountant without an accounting degree). When we need a relevant and effective higher education system more than ever, it appears to be breaking down on the measure that matters most. And it's not just higher ed's fault. Employers are to blame too.

Many studies and leaders consistently point to a "skills gap" as the big problem. The idea that we simply have a disconnect between jobs available and people with the right skills to fill them grossly oversimplifies the problem. Before we even get to the skills gap, it's obvious we have a huge communication and understanding gap. Higher education institutions and employers are not actively communicating and collaborating with one another. They don't even agree on simple things -- like the definition of "critical thinking." For an academic, those words have a very different definition than they do for a corporate leader. And there is clear evidence from the Gallup-Purdue Index -- a massive representative study of college graduates -- that colleges and universities aren't even providing the most important fundamentals linked to long-term career and life success.

A staggering 25% of all college graduates missed the mark on all six critical emotional support and experiential elements of their student experience. These graduates' outcomes -- on measures such as their workplace engagement and overall well-being -- show they fail to thrive in their careers and lives. If higher education was the auto industry, it would be forced to recall a quarter of all its graduates. Americans are a pretty perceptive lot. They feel that something is amiss, and they are right. They're not as prepared as they can or should be for success in the workplace. And the "fixes" are relatively straightforward.

What these fixes require is courage, not more data. It's no secret what works. Real-world work experience (in the form of internships, jobs and apprenticeships), long-term projects applied to solving real problems and mentoring and caring from staff and faculty are just a few of the things on the short list. The honest question is whether higher education leaders and their regional and national employer counterparts have the courage to change. First, to admit the current system isn't working the way we want it to, and second, to take the steps needed to get it on track. Neither is easy. And then, if leaders can do that, they will need to launch an all-out campaign to prove they are being successful. Otherwise, we risk Americans' overall belief in postsecondary education crumbling -- and that would mark the end of our economic, intellectual and moral leadership position in the world.