The selection of Pope Francis as the Person of the Year by TIME magazine has brought our attention to the Catholic church, its leadership, and its relevance to the world. One of the key factors that prompted TIME's editors to select Pope Francis was his outspokenness in pushing to make his Catholic religion more connected to the real world. This includes his encouraging Catholic leaders to expand their horizons beyond a sole focus on values issues, such as birth control and abortion, and his recent encyclical in which he focused on religion's relevance in ameliorating the problems of inequality and the poor in society today.

As TIME stated in its cover story announcing the selection of the Pope as Person of the Year:

"But what makes this Pope so important is the speed with which he has captured the imaginations of millions who had given up on hoping for the church at all. People weary of the endless parsing of sexual ethics, the buck-passing infighting over lines of authority when all the while (to borrow from Milton), 'the hungry sheep look up, and are not fed.' In a matter of months, Francis has elevated the healing mission of the church -- the church as servant and comforter of hurting people in an often harsh world -- above the doctrinal police work so important to his recent predecessors."

In short, it appears that Pope Francis is attempting to make religion, his religion at any rate, relevant to today's problems.

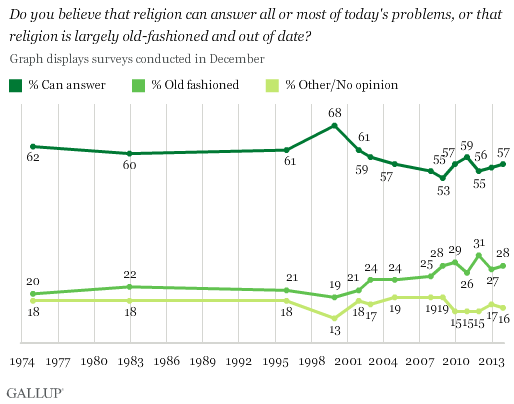

We have data that speak to this. At this point, 57% of all American adults say that religion "can answer all or most of today's problems" while 28% say that religion is old-fashioned and out of date. If you ponder the chart below, it's interesting to note there hasn't been a great deal of change on this measure in recent years. Prior to 2001, the percent saying that religion can answer all or most of today's problems was slightly higher, including an apparently random uptick in December 1999, but other than that, not higher by much.

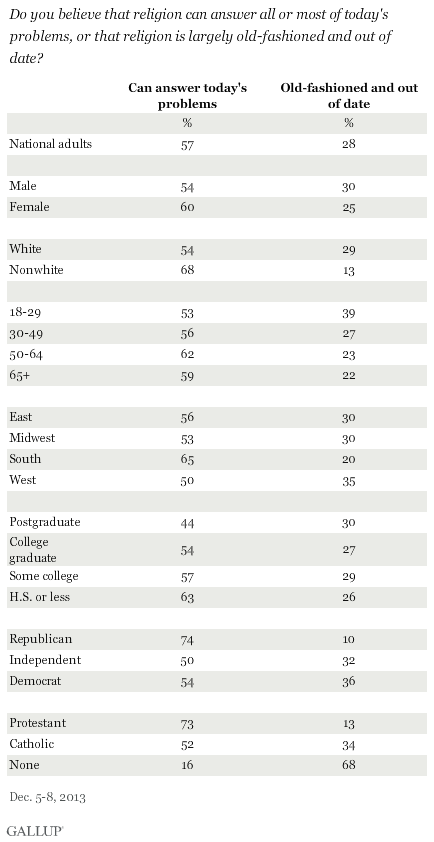

Although the majority of Catholics around the world don't live in the U.S., it's our focus here to look at how American Catholics answer this question. We see that the average Catholic is below average in terms of their views of the relevance of religion for today's problems. Fifty-two percent of U.S. Catholics say that religion can answer today's problems, and 34% say it's old-fashioned and out of date. (The accompanying chart includes not only the breaks by religious identity but by other demographic categories of interest as well.)

One hypothesis is that Catholics are below average in their collective belief that religion can answer today's problems because they believe their particular religion is out of date. If this is the case, then we would expect that religious Catholics would be less likely to say religion can answer today's problems than those who are equally religious but who identify with other religions.

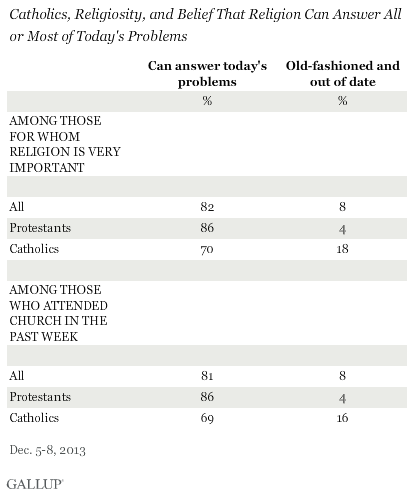

That is, in fact, what we find. I looked at those individuals who reported having attended religious services within the last seven days, a good measure of overall religiosity. We find that Catholic church attenders are 12 percentage points below the average of all frequent church attenders in saying that religion can answer today's problems -- 69% versus 81%. Similarly, among those who say religion is very important in their daily lives, 70% of Catholics say religion can answer today's problems, as opposed to the overall sample where 82% of those in the "religion very important" category replied similarly.

In other words, even controlling for religiosity, Catholics are less likely to say that religion can answer today's problems than other equally religious individuals who identify with other religions.

Now, there is a lot going on here, and it's very difficult to control for a lot of other factors that might be intervening in this relationship, including underlying demographic differences in religious Catholics versus religious non-Catholics in the U.S. (For example, Catholics are much less likely to live in the religion-rich culture of the South, which could affect their perceptions in some ways).

Still, it seems reasonable to assume on a preliminary basis that Pope Francis has a good deal to work with in terms of his flock here in the U.S. Even among those Catholics who are religious in a conventional sense, there is less of a belief that religion can answer today's problems than is the case for equally religious Americans of other faiths. This could -- in theory -- reflect Catholics' beliefs about the relevance of their Catholic religion. Perhaps if Pope Francis continues his vigorous attempt to make Catholicism relevant in today's world, American Catholics' views will shift over time.