The significant problems that some veterans are having with health services provided by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs -- or the lack of said services -- has become a red-hot news story in recent weeks, just as we approach the annual tribute the United States pays its veterans next Monday on Memorial Day.

Just how many Americans are, in fact, veterans?

There were times in fairly recent American history when a good proportion of the male population shared the common experience of having served in the military.

That is no longer the case. The primary causal factor is the draft, instituted in 1940 when it became evident that the U.S. was likely to be drawn into World War II. The draft affected most men in one way or the other from that point until early 1973, when the Selective Service System effectively shut it down. Since then, American men have been essentially draft free, and that is dramatically evident in veteran status data.

Majorities of men who reached age 18 during the time of the draft ended up serving in the military, in sharp contrast to the small numbers of those who came of age after the draft ended who have served.

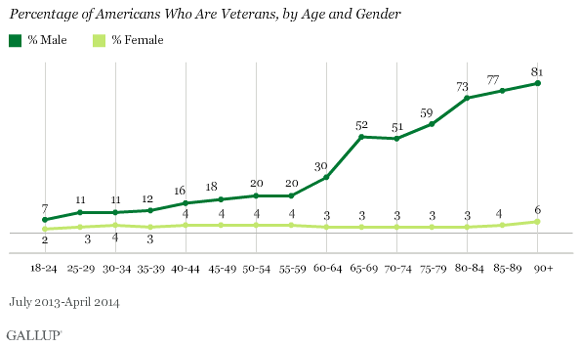

Overall, Gallup interviews with about 290,000 adults 18 years and older over the past 10 months show that about 13% report having served in the military. That's the population average, from those aged 18 to those aged 98, and among men and women.

But women were never subject to the draft, and the data clearly show the results. About 3% of women of all ages served in the military, and that is a remarkably constant percentage across the entire age spectrum.

Among men, it's an entirely different story.

The draft ended in January 1973. Men who reached age 18 in 1972 or before were, in theory, susceptible for the draft. Those who were 18 in 1972 were born in 1954. So anyone who was born in a year prior to 1955 was at least briefly draft eligible. The data represented in the accompanying chart were collected from July 2013 through April of this year, thus making any male who was about 60 or older at the time of the interview eligible for at least the tail end of the draft. (A few very old men in the sample might have been too old for the draft by 1940, but those would be so few that they wouldn't affect the data.)

Of course, those in their very early 60s were coming of draft-eligible age just as the draft was winding down, so we would expect fewer of them to be veterans, as the data in fact show. The big jump in veteran status begins to be seen among those men 65 and older, who were born in 1948 and earlier. The very youngest of these older men would have become draft-eligible in 1966 -- just as manpower requirements for the Vietnam War were escalating. Clearly the draft did, in fact, affect those who are now ages 65 to 74, 51% to 52% of whom retrospectively tell us that they served in the military.

The next big jump in veteran status is evident among those aged 75 to 79 at the time of the interview, and in particular among those 80 years and older.

Men 80 and older were born in 1933 or earlier. So the youngest of these (those 80 in 2013) would have hit age 18 in 1951, in the middle of the Korean War, and those older than that would have become draft-eligible in the time period that included World War II and its immediate aftermath. To be more precise, those who became age 18 in the last year of World War II (1945) were born in 1927, and would be 86 at the time of the interview. Those in the sample 85 and older were most likely of any age group to have served in the military in general, and many most likely served in World War II.

What about the younger end of the age spectrum? Veteran status is low and fairly level from about age 23 on up to age 35, when it begins to creep up. Among those aged 49 to about 59, 20% are veterans. These men came of age after Vietnam and after the draft, born between 1954 and 1964, and therefore reaching age 18 between about 1972 and 1982.

Thus, it should be no surprise on Monday when we watch Memorial Day parades and see a disproportionately older group of men and relatively few younger men -- and relatively few women -- walk by.

Of course, one fascinating and important research question is the difference that serving in the military makes across the various aspects of a person's life. That's hard to quantify, in part because veteran status encompasses a very, very wide set of different experiences.

Take those who are now in their mid-to-late 60s and early 70s, who were in the main target zone for the draft during the Vietnam War. Some of the veterans of this age group in fact served in combat in Vietnam, survived, and almost certainly were affected by that experience in a number of profound ways. Others of the same age group may have served in the military, but were not in combat at all, and although affected in a general sense, were certainly not affected in the same way as those who were directly in harm's way. Same for the older men who served during the Korean War and World II. Not all of these veterans, by any means, were in combat situations. It was a far different experience to have been an infantryman in the Chosin Reservoir campaign in Korea, or a B-17 pilot flying over Germany, or a Marine on Iwo Jima in World War II, than it was to have been in a largely non-combat role in those wars. And for the smaller number of younger veterans, military service certainly had a dramatically different impact among those who were directly involved in combat in the Iraq or Afghanistan wars than among those who were not.

Even though military service is no longer obligatory for American males, and even though a small percentage of Americans below the age of 60 have, in fact, served in the military, those who do are serving in an institution that has the highest confidence rating of any institution in the nation. This creates a paradox of sorts. Both the military and the VA are part of the federal government. The public has a very low confidence in the federal government in general. The news coming out of the VA shows a federal agency that many are calling bureaucratically inept. Thus, the public most likely views the VA situation as one more example of an inefficient government apparatus. But in this instance that inefficiency is affecting men and women connected with one of the few aspects of the government that is perceived as highly efficient. This situation thus has the potential to resonate with Americans in many specific ways, and may be a scandal that does not quickly go away.