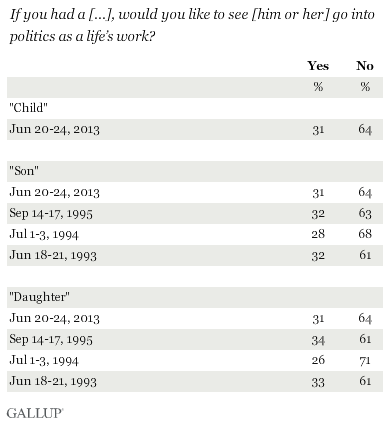

PRINCETON, NJ -- By a 2-to-1 margin, 64% to 31%, Americans would not like their child to go into politics as a career. The results are the same whether the question is asked about a "child," a "son," or a "daughter." There has been little change in the percentage of Americans who would favor a political career for their son or daughter over the past two decades.

The results are based on a June 20-24 Gallup poll, and find generally little change in the desirability of politics as a profession even as trust in government and confidence in political institutions, particularly Congress, are low.

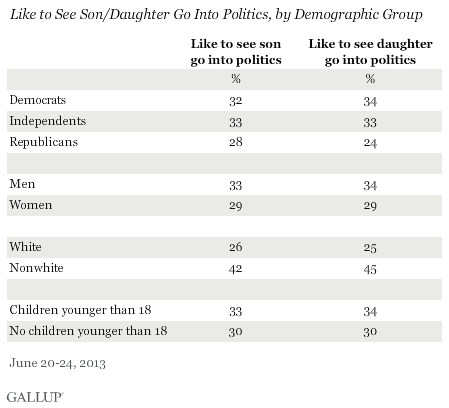

The largest demographic differences among major subgroups are by race, with nonwhites much more likely than whites to say they would like to see their son or daughter go into politics. This is not a reaction to the fact that the current president is black, as Gallup has found that same racial difference when the question was asked in the 1990s when George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton were president.

The racial differences may be behind the slight tendency for Democrats to favor a political career for their sons and daughters more than Republicans do, with a larger party difference for daughters. There are also small, but not necessarily meaningful, differences by gender and being a parent of a young child.

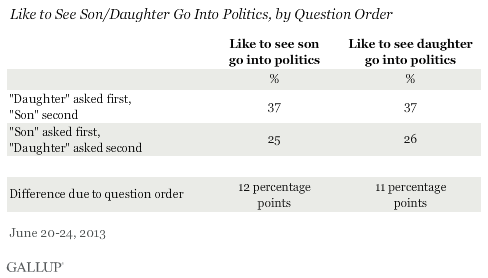

Americans More Likely to Favor Political Career When Asked About Daughter First

The 31% of Americans who favor a political career for their son or daughter can be seen as an average because respondents answer the questions differently depending on the order in which they are asked. Specifically, Americans are significantly more likely to say they would like both their daughter and son to go into politics when they are asked about a daughter first.

When Gallup asks about a daughter going into politics first, 37% say they would like to see their daughter go into politics. But 37% also say they would like to see their son go into politics when asked about it after being asked about a daughter going into politics.

In contrast, when Gallup asks about a son going into politics first, the percentage wanting to see their son go into politics is 12 percentage points lower, at 25%. And the percentage wanting their daughter to go into politics is lower, at 26%, when asked after the question about a son going into politics.

These order effects have been consistent in the past. This suggests that Americans may be interpreting the question as one about gender equality when asked about a daughter first, and therefore that makes them more likely to favor a political career for their children of either sex. When asked about a son first, Americans may interpret the question as more straightforward one about the desirability of a political career and are less likely to favor it for either a son or daughter in that circumstance.

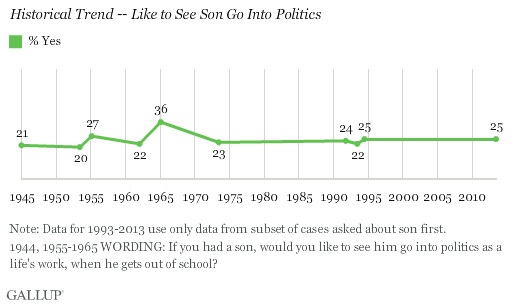

Americans Never Strongly in Favor of Sons Going Into Politics

Gallup first asked about both sons and daughters going into politics in 1993, but has asked the question about sons as far back as late 1944 into early 1945. The historical trend suggests that Americans are no more negatively disposed to a political career now for their son than they were in the past. The high point in favoring a political career for a son was 36% in 1965, at a time when Americans were still rallying around President Johnson after he took office following the death of John F. Kennedy.

In fact, 1965 was the only time when more than 30% of Americans said they wanted their son to go into politics, taking into account the order affects in recent updates by only using the format when son was asked first. That includes 21% in a poll conducted in late 1944 into early 1945, as the U.S. was fighting in World War II.

Implications

Most Americans would not prefer their son or daughter to go into politics as a career, and this preference has not changed appreciably over time even as Americans' frustration with the government has grown.

Compared with other possible careers, politics ranks fairly low in Americans' pecking order. Another historical Gallup question has consistently found Americans mentioning a career in medicine or technology as the one they would advise a young man or woman to pursue. A career in politics or government has historically ranked well behind those professions as well as law, business, teaching, and engineering.

Survey Methods

Results for this Gallup poll are based on telephone interviews conducted June 20-24, 2013, with a random sample of 2,048 adults, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

For results based on the total sample of national adults, one can say with 95% confidence that the margin of sampling error is ±3 percentage points.

Interviews are conducted with respondents on landline telephones and cellular phones, with interviews conducted in Spanish for respondents who are primarily Spanish-speaking. Each sample of national adults includes a minimum quota of 50% cellphone respondents and 50% landline respondents, with additional minimum quotas by region. Landline and cell telephone numbers are selected using random-digit-dial methods. Landline respondents are chosen at random within each household on the basis of which member had the most recent birthday.

Samples are weighted to correct for unequal selection probability, nonresponse, and double coverage of landline and cell users in the two sampling frames. They are also weighted to match the national demographics of gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, region, population density, and phone status (cellphone only/landline only/both, and cellphone mostly). Demographic weighting targets are based on the March 2012 Current Population Survey figures for the aged 18 and older U.S. population. Phone status targets are based on the July-December 2011 National Health Interview Survey. Population density targets are based on the 2010 census. All reported margins of sampling error include the computed design effects for weighting.

In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

View methodology, full question results, and trend data.

For more details on Gallup's polling methodology, visit www.gallup.com.