Story Highlights

- 67% of Indians are confident in the honesty of elections

- Prime Minister Narendra Modi's approval rating slightly depressed

- Regional differences may influence the election

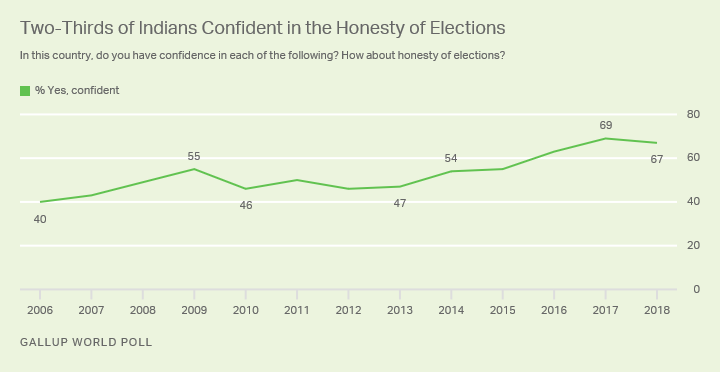

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- Confidence in India's electoral process remains near a record high as voting starts Thursday in the world's largest democracy. India's five-week general election begins with more than two-thirds of Indians (67%) expressing confidence in the honesty of their country's elections, the highest level Gallup has recorded in the runup to a general election in India.

These findings from a Gallup World Poll survey conducted in India in October-December 2018 highlight a rising trust in the electoral process since before the previous election. In 2013, less than half of Indians (47%) expressed confidence in the honesty of elections prior to the country's 2014 general election. The 20-percentage-point increase since then follows a successful transfer of power to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Prime Minister Narendra Modi after a decade of rule by the Indian National Congress and its allies.

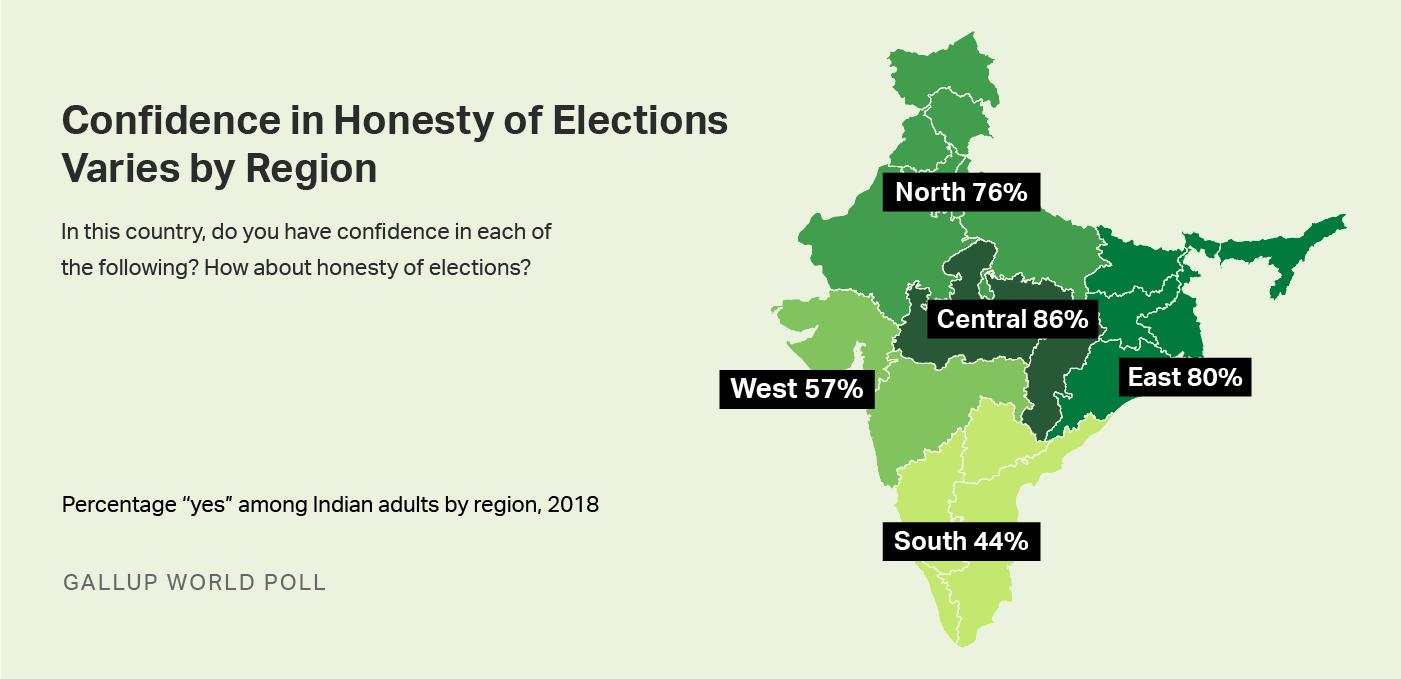

While perceptions of electoral integrity have increased overall, not all Indians are equally confident. Slightly more than half of urban residents (52%) have confidence in the honesty of their country's elections, compared with 69% of rural residents. More than three-quarters of Indians in the Central, East and North regions of the country have confidence in the electoral process, compared with less than half of those in South India (44%).

The high overall confidence in elections will be important given some key challenges that may affect the voting process. First, all voters will use electronic voting machines during the election. These machines have successfully reduced some electoral fraud in India, yet some researchers and politicians claim that the machines can be hacked and the results manipulated. However, the Election Commission of India has underscored that the machines cannot be tampered with and that it has implemented extensive safeguards.

Additionally, there have been mounting concerns about the role of disinformation in the runup to the election. Fake news stories have been circulated on Facebook and among India's 230 million WhatsApp users. While the goal is often to discredit political opponents, the spread of fake news has already stoked tensions between political parties and led to violence.

Among Indians who have a mobile phone that can be used to access the internet, 60% have confidence in the honesty of India's elections. By comparison, those without a phone that has internet access are more likely to view India's elections positively: 73% have confidence in elections. Even when accounting for urban or rural status and education, Indians with internet-enabled mobile phones are less likely to express confidence in the electoral process.

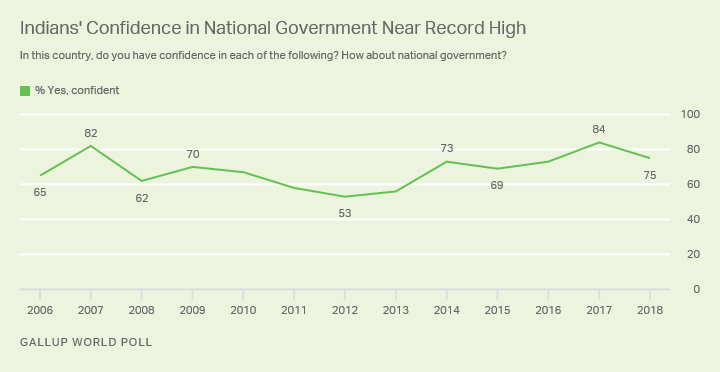

Confidence in National Government Has Improved Under Modi, but Has Declined Over Past Year

Although Indians' confidence in their national government has increased since Modi and the BJP took office in 2014, the percentage slipped by nine points between 2017 and 2018.

This recent decline in confidence coincides with weakening economic growth in India. While India has one of the highest GDP growth rates in the world (6.7% in 2017), it has seen a slowdown since 2015 (8.2%) and currently lags behind many of its regional and emerging market peers. Furthermore, the unemployment rate reached a 45-year high in January.

Some economists have placed the blame on Modi's surprise demonetization policy, which voided most currency in 2016 in an effort to flush out money gained through corruption, illegal activities and the black market. While this decision did not immediately affect Indians' confidence in their national government, Indians may still be experiencing long-term effects of the policy. The Reserve Bank of India has estimated that this caused a 1% decline in GDP and cost at least 1.5 million jobs.

Modi's Approval Slips Ahead of Election

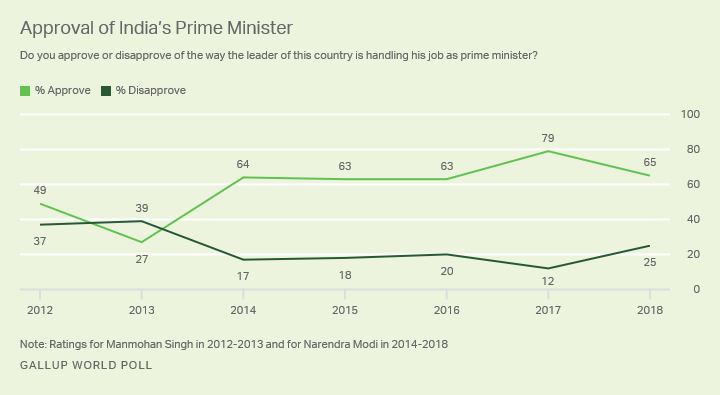

This decline in confidence in the national government coincides with Modi's weakening job approval. While Modi recorded a record-high 79% approval rating in 2017, his approval is down 14 points in the runup to the 2019 election. Additionally, he faces his highest disapproval rating while in office (25%) and confidence in the national government currently outpaces Modi's own level of job approval. This suggests that support for Modi may be weakening. However, the BJP remains significantly stronger than the incumbent Indian National Congress was ahead of the previous election. Only 27% of Indians approved of then-Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

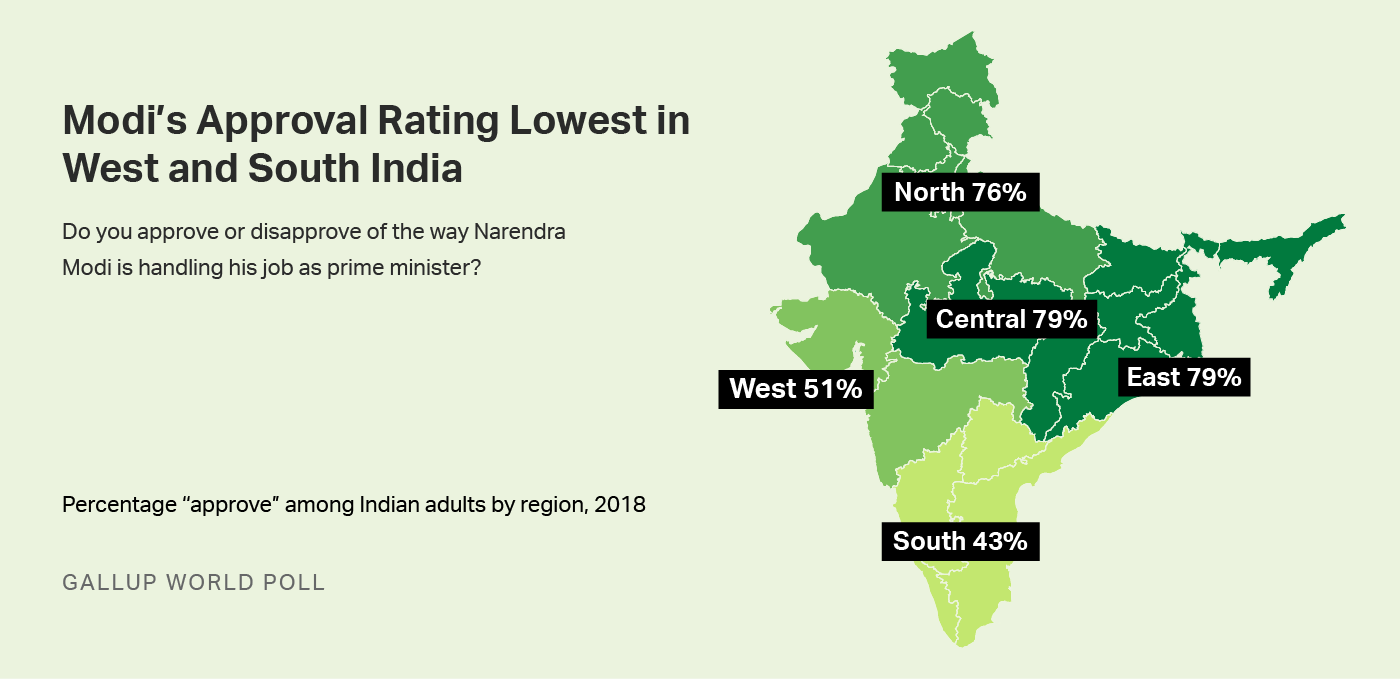

Modi remains particularly strong in the Central, East and North regions of India, where over three-quarters of Indians approve of his job performance. However, he faces notably weaker approval in South India, which is dominated by smaller regional parties and where the BJP is historically weaker. In this region, 44% of the population approves of how he is handling his job as prime minister. Modi maintains especially strong approval in some of India's most populous states, Uttar Pradesh (83%) and Bihar (93%). While he has a lower approval rating in other large states, such as Maharashtra (51%) and West Bengal (61%), he still maintains approval from over half of the population in these areas.

Modi faces his weakest approval in South and West India, where 43% and 51%, respectively, approve of his job as prime minister. In particular, Modi faces low approval in his home state of Gujarat in West India. Modi, who was Chief Minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014, has an approval rating of 50% from Indians residing there.

Bottom Line

India enters its five-week election period with near-record levels of confidence in key institutions. This is especially important given the sheer scope of the election: It requires 11 million poll workers and security officers to oversee voting at over 800,000 polling stations across the vast country. Indeed, India is well-positioned to weather many of the election-related storms it will likely face related to disinformation, polarized rhetoric and sectarian conflict. A successfully administered election will only further solidify confidence in India's institutions and strengthen the electoral process in the world's largest democracy.

Furthermore, Modi and the BJP look poised to maintain control of India's parliament, the Lok Sabha, when voting ends in May. Despite the BJP's lack of success in increasing employment and addressing the challenges faced by rural Indians, confidence in the national government and approval of Modi's job performance remain widespread and near record highs heading into the election.

However, a weaker economy has chipped away at some Indians' perceptions of the government. This may threaten the BJP's absolute majority in the Lok Sabha and force Modi to partner with other parties in order to govern. This new government will face a host of challenges, including expanding employment, navigating geopolitical tensions with Pakistan and addressing rural distress.

For complete methodology and specific survey dates, please review Gallup's Country Data Set details.

Learn more about how the Gallup World Poll works.