Germans' personal well-being has declined since the European debt crisis began, according to analysis of data collected in the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index survey. This is hurting the German economy.

Senior executives in Germany must get a handle on this problem, and fast.

Gallup categorizes individuals' overall well-being as "thriving" (strong, consistent, and progressing), "struggling" (moderate or inconsistent), or "suffering" (at high risk). People who have thriving well-being are better off in every way that matters. They have good health, are integrated into the community, enjoy a rewarding career, have good finances, and meet with friends frequently. Their well-being affects their workplaces as well.

The Five Essential Elements of Well-BeingFor more than 50 years, Gallup scientists have been exploring the demands of a life well-lived. More recently, in partnership with leading economists, psychologists, and other acclaimed scientists, Gallup has uncovered the common elements of well-being that transcend countries and cultures. This research revealed the universal elements of well-being that differentiate a thriving life from one spent suffering. They represent five broad categories that are essential to most people:

|

But overall, only 26% of German workers strongly agree with the statement "My organization cares about my overall well-being." This has serious consequences for the German workforce. People with a thriving sense of well-being are more productive, miss fewer days of work, and are less likely to get sick, Gallup research finds. Those attributes affect a company's profitability, but none more so than this one: Workers with high well-being are more likely to be engaged in the workplace.

The bad news is, far too many German workers aren't engaged. Gallup analysis shows that 14% are engaged, 64% are not engaged, and 23% are actively disengaged. This means that 87% of German employees are not contributing their utmost in the workplace. And the percentage of actively disengaged employees has been growing steadily since 2001.

Senior executives in Germany must get a handle on this problem, and fast. If 87% of employees are not bringing their best effort to work every day, it's because companies are not creating a culture that meets employees' needs and expectations. The consequences of this are very costly. (See graphic "Active Disengagement Increasing in Germany.")

What went wrong?

The high rate of disengagement in Germany contradicts the characteristic image of German workers -- the words "lazy" or "indifferent" don't typically spring to mind. And in truth, many employees in Germany have a positive attitude toward work and performance.

For instance, workers were asked what they would do if they inherited enough money to quit working. Seven out of 10 said they would continue to work -- a percentage that has remained stable since 2001. The majority of workers (80%) believe that they can get ahead if they work hard, 76% say their current work represents the ideal work for them, and 30% strongly agree that they're paid appropriately for the work they do (the greatest rate of agreement with this question since 2001).

Further, analysis of data from the Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index indicates that the percentage of workers who are engaged doubles and the percentage who are actively disengaged is nearly halved when workers are treated as partners rather than as subordinates.

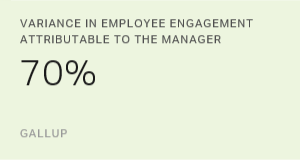

The key point that senior executives must understand is this: The problem with disengagement isn't solely the responsibility of workers. Gallup's research has shown that managers can play a key role in raising engagement levels when they address employees' most crucial expectations. Therefore, the most important decision a company's leadership makes is who it names as managers.

Gallup has identified 12 key employee needs that form the foundation of strong employee engagement. (See "Feedback for Real" in the "See Also" area on this page.) When these elements are examined by engagement level, a clear pattern emerges. Some examples:

German management is too top-down, and that approach squanders productivity and profitability.

- Using potential: 90% of employees who are engaged strongly agree that they have an opportunity to do what they do best every day at work; among actively disengaged workers, the percentage who strongly agree drops to 21%.

- Giving positive and constructive feedback: 79% of workers who are engaged strongly agree that they received praise or recognition for doing good work in the last seven days, compared with 4% of actively disengaged workers who strongly agree. Similarly, 75% of employees who are engaged strongly agree that someone at work has talked to them about their progress in the last six months; among actively disengaged employees, only 2% strongly agree.

- Sense of caring: 93% of engaged employees strongly agree that there is someone at work who seems to care about them as a person, while only 5% of actively disengaged employees strongly agree with this statement.

- Development: While 86% of engaged employees strongly agree that someone at work encourages their development, only 1% of actively disengaged employees strongly agree with this statement.

- Integration: 93% of engaged German workers strongly agree that their opinions seem to count at work. But only 3% of actively disengaged workers strongly agree with this statement.

Sadly, these attributes don't fit the characteristic image of German managers either. Often, managers are valued for their technical expertise, product orientation, and authority. Simply put, German management is too top-down, and that approach squanders productivity and profitability while doing little for employees' well-being. This must change.

Senior executives of German companies must recognize that building employee engagement has to happen within each company, regardless of the company type. Executives should look closely at how their front-line supervisors manage employees, day in and day out.

The good news is, German businesses that have done this successfully have significantly higher levels of engagement. Gallup's analysis reveals that the engagement rates achieved overall by these companies -- 35% engaged, 52% not engaged, and 13% actively disengaged -- are much better than the national average. And engaged employees also have a much higher level of well-being. Employees who strongly agreed with the statement "My organization cares about my overall well-being" were more engaged, compared with those who gave any other rating to this item.

Managers' workloads have increased over the past 10 years, which has made everything they do more difficult, and this may sound like one more thing to do on a manager's long list. But taking action on correcting this problem must start at the local level, workgroup by workgroup and manager by manager.

And solving this problem should not be treated like just another item on a checklist. Creating a culture of engagement will require German companies to hire and develop managers whose attitudes and actions will increase the well-being of their workforce -- managers who can motivate employees by capitalizing and building on employee talents, recognizing their efforts, and providing regular feedback on their performance.

The timing has never been so crucial. No one knows how the European debt crisis will be resolved (though Germans suspect they'll be funding it), and things will probably get worse before they get better. If ever there was a time for German executives to make engagement their highest priority, it is right now.

The Costs of Disengagement

|

Survey Methods

Results are based on telephone interviews conducted between October 4 and December 30, 2011, with a random sample of 1,323 workers, aged 18 and older, living in Germany. Interviews are conducted with respondents on landline telephones and cellular phones. For results based on the total sample of workers, one can say with 95% confidence that the maximum margin of sampling error is ±3.9 percentage points. Margins of sampling errors vary for individual subsamples. In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.