In many cases, employers should examine their management practices and criteria for selecting managers.

Economists and policymakers have said for years that China's investment- and export-driven growth is increasingly unsustainable and that Chinese consumers must spend more money to support the country's expanding economy. In recent years, for example, the Chinese government has implemented stimulus programs that offer rebates for rural Chinese who buy home appliances and subsidies for upgrading their vehicles.

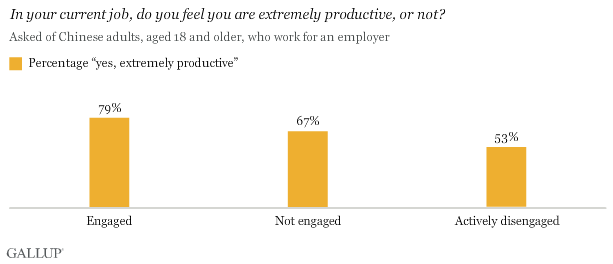

Ultimately, the task of engaging Chinese consumers is in the hands of thousands of businesses working to carve out new markets, build strong brand reputations, and create loyal customers. Those efforts will largely come from engaged workers, who are more likely than employees who are not engaged or who are actively disengaged to say they are "extremely productive" in their current job.

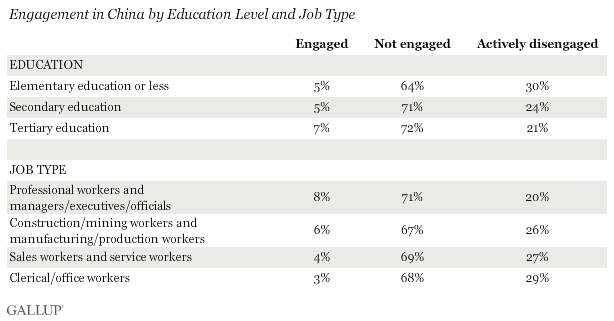

Engagement is low across education levels and job types

Unfortunately, China has one of the lowest rates of employee engagement in the world. Just 6% of Chinese workers are engaged in their jobs, while 68% are biding their time in the "not engaged" category, and 26% are actively disengaged and likely to be disrupting the efforts of their coworkers.

What's more, low engagement is pervasive among Chinese workers across different job types and education levels. The 7% engaged rate among college-educated workers is not meaningfully different from the 5% rate among those with an elementary education or less. And even among professional workers and managers -- job types often characterized by high levels of status and autonomy -- engagement is relatively rare at 8%. More worryingly, only 4% of sales and service workers -- on which Chinese companies will rely to attract new customers in an increasingly consumer-based economy -- are engaged.

Getting Chinese workers engaged

What will it take to engage more Chinese workers in their jobs? In many cases, employers should examine their management practices and criteria for selecting managers. Gallup CEO Jim Clifton noted in his blog that Chinese workplaces are often characterized by "command-and-control" hierarchical structures. And in many cases, people are not selected as managers for their ability to engage and develop employees.

This practice is especially troubling because Gallup's research shows that managers have a critical impact on their employees' engagement levels. China's results are particularly low on item 7 of Gallup's 12-item employee engagement survey, the Q12 -- "At work, my opinions seem to count." Only about one in eight Chinese employees strongly agree with this statement, versus a median of about one in three employees among all 142 countries included in Gallup's research on the State of the Global Workplace.

This practice is especially troubling because Gallup's research shows that managers have a critical impact on their employees' engagement levels. China's results are particularly low on item 7 of Gallup's 12-item employee engagement survey, the Q12 -- "At work, my opinions seem to count." Only about one in eight Chinese employees strongly agree with this statement, versus a median of about one in three employees among all 142 countries included in Gallup's research on the State of the Global Workplace.

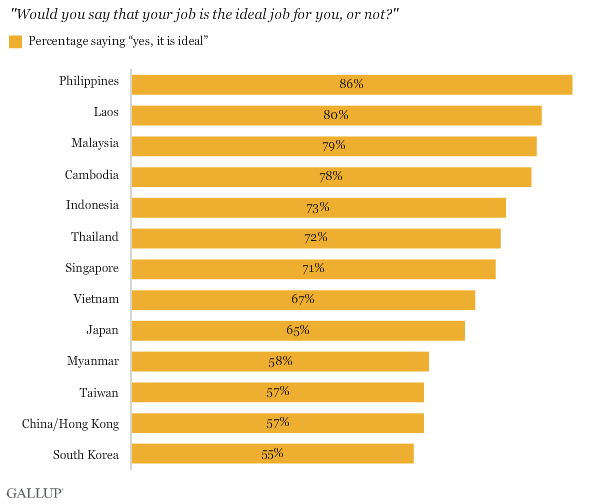

At the macroeconomic level, Chinese leaders seek to reform the country's economy from one based predominantly on manufacturing and dominated by large state-owned enterprises to one that better promotes innovation and entrepreneurship as key sources of indigenous growth. This diversification will require a greater focus on another critical aspect of employee engagement: ensuring that workers are in roles that best use their talents. Gallup's 2012 surveys reveal that 57% of Chinese workers say their job is ideal for them -- among the lowest percentage in East and Southeast Asia.

Engaged employees are happier with their lives

Workplace conditions are also important for improving the Chinese people's quality of life. Despite China's remarkable economic growth, its residents' life ratings have risen only modestly in recent years. In 2006, 13% of Chinese evaluated their present and future lives highly enough to be considered thriving; in 2012, that figure was 20%. Among Chinese employees, however, perceptions of life overall are strongly linked to their level of engagement at work. Engaged workers are four times as likely as actively disengaged workers to be thriving: 32% of engaged workers are thriving versus 8% of actively disengaged workers.

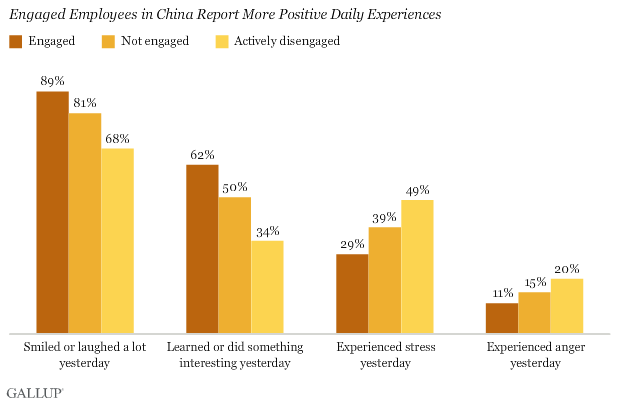

Engaged workers in China are also more positive about their day-to-day experiences on a broad range of measures. For example, they are more likely than actively disengaged workers to say that they smiled or laughed a lot the previous day. Engaged workers in China are also more likely to say they learned or did something interesting the previous day and less likely to have experienced stress or anger.

The powerful relationship between Chinese employees' workplace experience and their overall outlook on life has important implications for stability in a country whose leaders have made social harmony a top priority. As more Chinese organizations come to adopt employee-centered management styles, those that retain restrictive, controlling management structures reminiscent of the country's once-dominant danwei work units are increasingly likely to become breeding grounds for worker dissatisfaction.

The next 20 years will be a time of rapid change for the Chinese economy as government and business leaders focus on the transition to more sustainable sources of development and job growth. Along the way, policymakers will be concerned with improving the way Chinese people view their lives and with avoiding social instability. Improving workplace conditions so Chinese employees are more likely to feel motivated and empowered will speed the country's transition to a more consumer-focused economy -- and it will boost workers' quality of life.