The earthquake that hit Nepal on April 25 devastated a fragile country that was already vulnerable from a combination of a high population density, poverty, old and poorly constructed buildings and extensive corruption. The road to recovery appears to be a long one.

Access to food and shelter and passable roads to rural areas were already problems in Nepal before the deadly earthquake in April, but the corruption that a strong majority of Nepali (72%) say is widespread in their government is proving to be yet another barrier to relief efforts. To that point, since the quake, reports have surfaced about relief goods being delayed by Nepal at the Indian border and at the country's only international airport. It's also been reported that the government is collecting import duties on these goods. Furthermore, donated monies cannot be distributed in the country unless they go directly into a Nepali government relief fund. This has made some potential donors skeptical about the ultimate destination for these funds.

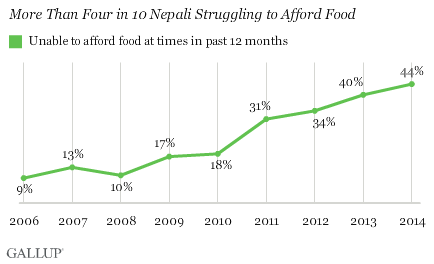

Meeting basic needs has long been a challenge for many in this underdeveloped country. This challenge has only become more difficult as Nepali have increasingly reported struggling to afford food and adequate shelter over the past decade. Before the earthquake, more than four in 10 Nepali said they had been unable to afford the food that they or their family needed at times during the past 12 months. This is nearly five times higher than it was when Gallup first surveyed Nepal in 2006, underscoring the dire nature of the situation that has only been exacerbated by the earthquake.

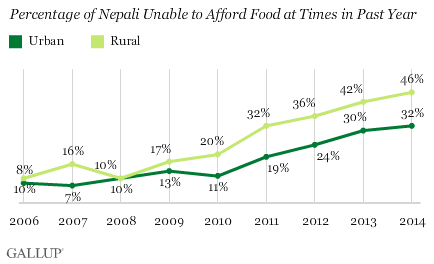

Rural Nepali are more likely than urban Nepali to report problems affording food, and it is the rural areas of the Kathmandu Valley that have been hardest hit by this disaster. They face the biggest crisis.

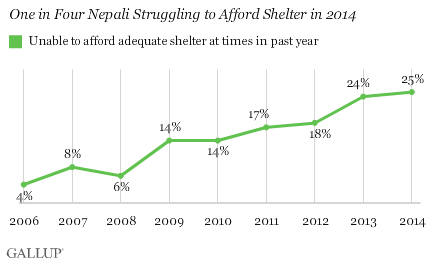

The quake leveled buildings in a large area of the Kathmandu Valley, flattening entire villages, and leaving many people who already lacked adequate shelter completely homeless. The United Nations reports that more than 130,000 homes have been destroyed, and according to U.S. Marine Brig. Gen. Paul Kennedy, who is working on relief efforts in Nepal, shelter right now is what the people immediately need most.

Adequate shelter has also become more of a challenge for Nepali over time, as 25% nationwide now report being unable to afford adequate shelter for themselves or their families at times in the last 12 months. This percentage has been increasing steadily from only 4% in 2006.

Transporting relief supplies will be an exceptional challenge in Nepal as the roads and highways have never been easy to navigate and maneuver in this mountainous country. A drive of just 200 kilometers can take five hours or more to complete under normal conditions, and many places are not even accessible by roads. On a 2011 fieldwork visit to Nepal, I experienced this inaccessibility firsthand. The selected village we were going to for observation was only accessible by foot, and the walk to the village took several hours over mountainous trails. This is not uncommon in Nepal, which is home to the tallest peak in the world, Mount Everest.

The least accessible rural areas are also the most devastated by the earthquake, with many villages yet to be reached since the quake. Over the years, majorities of Nepali have expressed satisfaction with the roads and highways in the areas where they live, but rural Nepali have consistently expressed greater dissatisfaction than urban Nepali. In 2014, 58% of rural Nepali were satisfied with roads and highways compared with 74% of urban Nepali.

Scientists have long been speculating that a devastating quake would hit this region of the world due to its location on a fault line; with the last quake happening in 1934, scientists knew the area was due for another one. What makes this quake so devastating is not Nepal's location on the fault line, but rather the man-made conditions of corruption, overcrowding, poorly constructed and old buildings, and a population already challenged by a lack of food and shelter and the lack of infrastructure to deliver needed supplies. All of this was in place before the quake, but the effects are being felt even more so now afterwards. What this means for Nepal is a very long road to recovery.