American high school graduation rates are at an all-time high and unemployment is at a nearly historical low, according to current metrics. Because this country has been obsessed with these two indicators of education and job success for decades, you'd think we'd be declaring victory. But for some reason, we're not.

Angst over the performance of our education system and economy remains significant, despite improvement in these indicators. Yet many of us can't quite put our finger on why.

Maybe America needs to change how it keeps score on these critical aspects of our nation. Perhaps we also need to rethink success and reconsider how we go about achieving it.

Here's why. Even amid elevated high school graduation rates and lower officially recorded unemployment:

- Students in lower grades are much more engaged at school than students in higher grades.

- Enrollment in colleges and universities in the U.S. has declined for six straight years, while more than half a million current college students are in remedial education courses.

- Leading economists estimate that almost all (94%) new jobs created between 2005 and 2015 were contract, temporary or on-call work.

- Nearly a third of all working U.S. adults (34%) have gone backward in their overall income compared with five years ago; that is, they report making the same or less total income than they did five years ago.

- Only 12% of working U.S. adults say they have the "best imaginable job" for them, which tells us there is a lot of room to improve on the quality of work and workers' talent fit to jobs in the U.S.

Although it will remain valuable to continue quantifying school in terms of graduation rates and jobs in terms of hours worked, these metrics alone are incomplete and misleading. Simply put, when we dig deeper into the data and measure more qualitative aspects of education and jobs, the story of success and the path to it start to change dramatically.

Americans love to keep score. That's fine, but we need to keep score differently. And "differently" means more qualitative -- or behavioral economic -- indicators of success in addition to the quantitative -- or classic economic -- indicators.

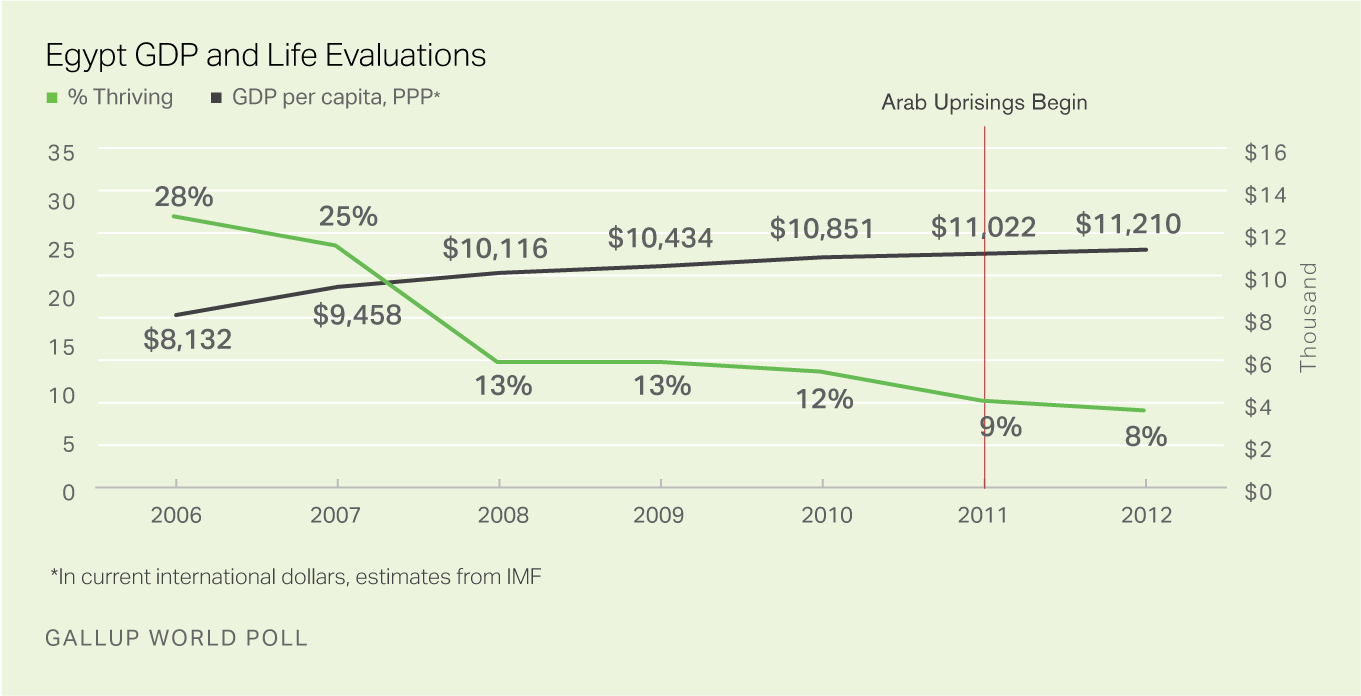

Let me offer a non-education illustration from recent events. At a country level, Gallup's monitoring of behavioral economic indicators such as life evaluation -- how people rate and evaluate their lives -- has proven to be a much better predictor of social unrest than classic economic indicators. In the five years before the Arab uprisings, for instance, a classic economic indicator such as gross domestic product (GDP) was steadily increasing in both Egypt and Tunisia. Based on that, most observers would have -- and did -- conclude that things were going fine in both countries.

But Gallup's measures of life evaluation in both countries were plummeting in the five years preceding the Arab uprisings -- and those indicators proved to be one of the most critical parts of the story. Certainly, there are cases in which both behavioral and classic economic indicators move together, but they also often diverge as they did in this instance.

If you apply this example to education and job preparedness, it shows how it's one thing if graduation rates are high, but it's another thing entirely whether graduates are prepared for work and college.

The fact that 2.4 million fewer students are going to college in the U.S. now than at the peak in 2011 -- and well over half a million college students are enrolled in remedial courses -- points to a serious blind spot in our current metrics.

So does the fact that only 11% of C-level business executives strongly agree that college graduates have the skills they are looking for.

So does the fact that Google -- one of the world's most admired employers -- is no longer asking about job applicants' grades or test scores because the company has found no correlation between them and success in jobs at Google.

All of this makes you wonder whether we are measuring all of the aspects of success -- and the paths to it -- that we ought to be.

The hard fact is that we have built an education system measured almost entirely by grades, test scores and graduation rates. In doing so, we have created a system that is engaging and inspiring only to those students who thrive on classic academic measures of success. Those who do well studying, who are very smart, who are good at memorization and who do well taking standardized tests are doing just fine in America's schools today.

But this system misses myriad talents and paths to success in the U.S. It underappreciates the massive performance debt that students from poor families and districts face as a result of hunger, health issues and more; devalues vocational and technical pathways; discourages nonlinear paths to success such as entrepreneurship; and convinces countless numbers of students that they aren't "college material."

We could be measuring many qualitative aspects of education in America. For example, when students work on long-term projects that take a semester or more to complete or have internships where they are able to apply what they are learning in the classroom, it doubles their odds of being engaged in their work later in life. Yet we aren't systematically measuring things like this.

We have also come to value a very narrow definition of what it means to have a "great job." Current employment data focus more on the number of hours worked than the quality of work such as what employees do in their jobs and whether their roles align with our skills, talents or interests.

What would happen if along with reporting the percentage of U.S. adults who are unemployed each month, we also reported how many people have great jobs and the factors that define "great jobs"? As an example, Gallup has learned that factors such as having flexibility and control over the hours you work and what you do at work -- such as being expected to be creative or think of new ways to do things in your job -- are critical dimensions of whether you feel you have a great job.

A more nuanced, qualitative scorecard on education and jobs is mission critical for America to fulfill its promise and potential. If we can add a behavioral economic set of indicators to our definition and tracking of education and job success, everything changes. If America doesn't change how it keeps score, we'll simply be winning in ways that don't really matter.

This article was reprinted in The Washington Post.