Highly religious Americans are significantly more likely than others to identify as Republicans. This is a robust, continuous facet of American society. Analysis shows that this relationship occurs within most demographic groups: Protestants, Catholics, Jews, men, women, all age groups, and across all regions of the country. I have called this the "R and R" rule: "Everything else being equal, the more religious an American is, the more likely they are to identify as a Republican."

One subset of this relationship has gained particular focus in recent years -- the continuing support of President Donald Trump by evangelicals despite news reports indicating that Trump's personal lifestyle, morals and presentation of self are not in sync with what one associates with highly religious people. This relationship has led to such headlines as: "Why Evangelicals Support President Trump, Despite His Immorality" and "Evangelicals, Other Christians Grapple With President Donald Trump's Contradictions."

There is little consensus on exactly how to define the group commonly referred to as evangelicals. We at Gallup have used a number of different definitions over the years. In my research, I isolate highly religious, white Protestants as the functional equivalent of this group. This excludes highly religious Catholics, blacks and others, but focuses on the main group of those usually considered to be under the evangelical umbrella.

The data clearly show the basic, predicted positive relationship between membership in this group and approval of the job Republican Trump is doing as president. For the year 2017, 68% of white Protestants who are highly religious approved of Trump's performance as president, compared with the 39% national average. Among moderately religious white Protestants, Trump approval dropped to 59%, and among nonreligious white Protestants, it was a substantially lower 44%.

As I've noted, the fact that highly religious white Protestants are more likely than others to approve of the job Trump is doing as president is not surprising from a historical perspective. No matter who the Republican president, our research (including my 2012 book; see Chapter 4) would have predicted that highly religious people would be above average in their support.

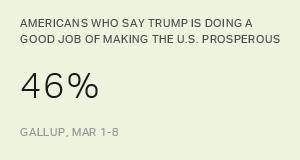

The key question in the current situation is the analysis of what it would take to create a disruption in the expected pattern. Obviously, what has transpired so far -- including the widespread visibility given to Trump's personal morals and behavior -- has not been enough to disrupt this normative relationship. Republicans as a group have stayed aggressively loyal to Trump, with an 85% approval rating in March, and the group of highly religious white Protestants have been loyal as well.

Some of the discussion in contemporary public discourse seems to assume that evangelicals start with a blank slate when they look at the president, making their approval decision from scratch based on the politician's particular attributes or behaviors. The reality is, in contrast, that most Americans' approach to a politician is highly conditioned by and controlled by the political context; namely, partisan identity. American evangelicals' starting point in evaluating Trump is their highly preconditioned and reflexive tendency to support Republican politicians. It would take a lot to change that predisposition.

Trump is in jeopardy of losing support from highly religious white Protestants if his policy stances and approach to politics begin to move away from a focus on traditional family structure, conservative norms governing sexual relations, pregnancy and marriage, keeping the government from infringing on perceived religious liberties, support for Israel, and the de-emphasis of government regulations. His personal lifestyle and moral values positions are well known (and were well known when he was elected) and new revelations on that front most likely will not change evangelicals' approval of the job he is doing.

Along these lines, a news report last week suggested that concerned evangelical leaders were pressing to meet with Trump in order to discuss these issues.

The report quoted an anonymous evangelical source as saying that "'It is a concern of ours that 2018 could be very detrimental to some of the other issues that we hold dear,' like preserving religious liberty and restricting abortion rights." In other words, it's not so much Trump's behavior per se, but the fact that attention given to his behavior could jeopardize the fundamental, underlying policies that undergird evangelicals' support for the president.

It is important to note that a third of highly religious white Protestants do not approve of Trump (and about three in 10 identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party, or are independents), so it's clear that evangelical support for Trump is not monolithic. Highly religious white Protestants who disapprove of Trump are significantly more likely to be college educated than the two-thirds who approve and are much more likely to be women. If there is to be a shift in the high levels of support given to Trump by highly religious white Americans, these groups are most likely going to be the vanguard of the movement.

The broader question is why highly religious Americans tend to support Republican politicians. A great deal has been written to attempt to answer that question, including hypotheses that this relationship is based on fundamental -- even genetic -- predispositions to approach and view the world in specific ways. Suffice it to say, again, that it's a relationship that appears robust and difficult to change. Trump's policies would need to shift markedly for him to lose support from highly religious whites, and Democrats would need to make fundamental shifts in their platform and policies to pick up more highly religious white Protestants, risking the alienation of some of their existing base in the process. None of this seems likely to happen in the near term in today's generally rigid political environment.

This article includes minor revisions from the original.