Gallup routinely asks Americans about the importance of religion in their everyday lives, and how often they attend religious services. We have not yet had an opportunity to ask these questions directly to President Donald Trump himself. And we have not asked Americans directly about Trump's religion. But I suspect that most Americans don't associate Trump with personal religiousness in the way that they did, for example, President Jimmy Carter.

Trump himself seems quite willing to talk about his religious background. In his speech at the National Prayer Breakfast last month, Trump said, "I was blessed to be raised in a churched home. My mother and father taught me that to whom much is given, much is expected. I was sworn in on the very Bible from which my mother would teach us as young children, and that faith lives on in my heart every single day."

Trump was raised a Presbyterian in Jamaica, Queens. While growing up, he and his family gravitated toward the Marble Collegiate Church in Manhattan, with its famous pastor Norman Vincent Peale (author of "The Power of Positive Thinking"). One of Trump's weddings was held at the church, and Trump has said he still remembers Peale's sermons from his younger days, calling Peale "one of the greatest speakers" he has ever seen.

More recently, Trump has been associated with the evangelical megachurch pastor Paula White, who delivered a prayer at Trump's inauguration. Trump attends church on occasion, although his lack of conventional religiousness was evident in a speech at Liberty University last year when he mispronounced the New Testament book 2 Corinthians -- calling it "Two Corinthians" rather than the accepted "Second Corinthians."

One expert on the faith of presidents said of Trump, "I don't think faith is a major part of his life." Trump's personal lifestyle and actions caused some religious leaders to emphatically come out against his candidacy last year -- including Albert Mohler, the president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, who argued that "character in leadership" still matters. Indeed, Trump's vice president, Mike Pence, a prominent evangelical Christian (although raised a devout Catholic), has been the visibly religious member of the Trump ticket.

The specific policy positions and actions that a president who is highly religious should take are debatable, of course. Some argue that religiosity should lead to a very liberal platform of redistributive economic policies aimed above all else at helping the less fortunate and the downtrodden; such policies are certainly not a major part of Trump's platform. Others say religiousness leads to specific value positions on issues such as abortion and same-sex marriage. In this regard, Trump has followed the evangelical lead in pushing policies that would defund international organizations that support abortion, including Planned Parenthood. Others would focus on religious liberty. Trump himself has argued that position strongly, particularly in his prayer breakfast speech when he said, "So I want to express clearly today, to the American people, that my administration will do everything in its power to defend and protect religious liberty in our land."

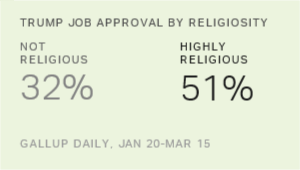

While we don't know what Americans think about Trump's religion directly, we do find that Trump's approval rating -- early in his presidency -- is significantly higher among highly religious Americans than among those who are not religious.

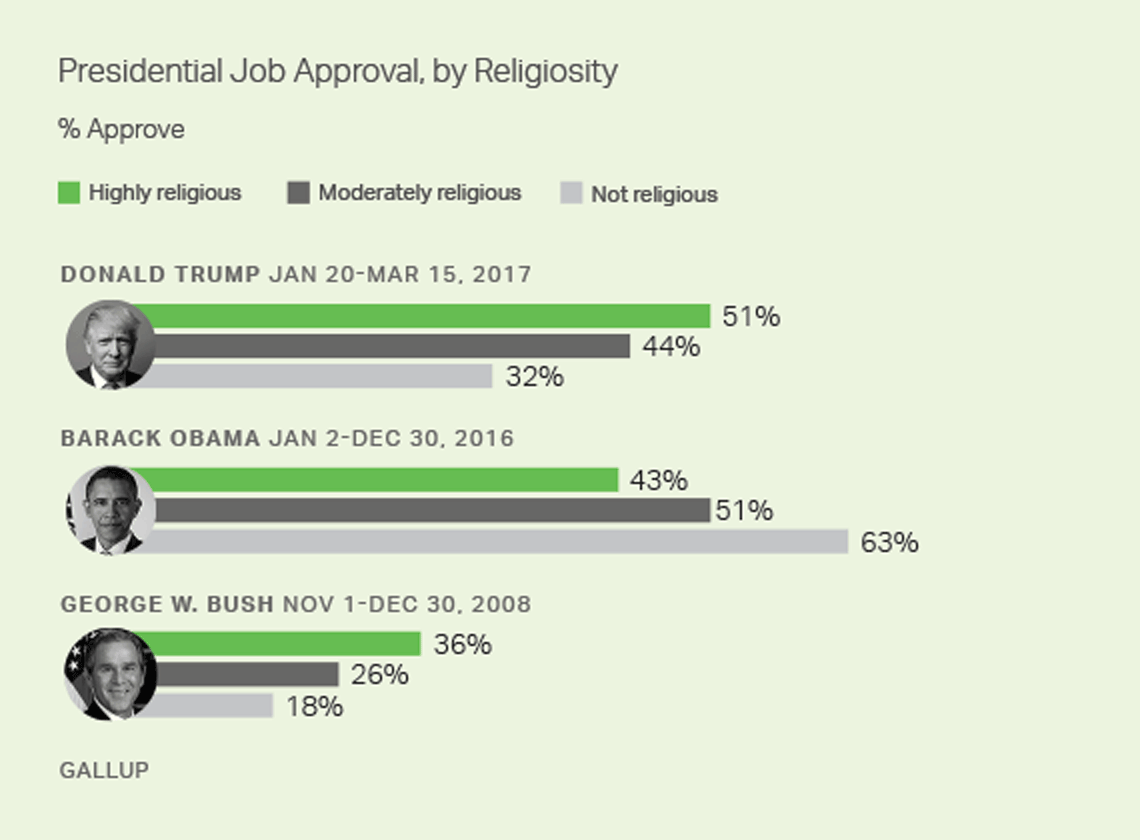

Here are the data, based on Trump's recent approval ratings, compared with Barack Obama's ratings for all of 2016 and two months of tracking data from November and December of George W. Bush's last full year in office (2008). I'm using that period for Bush because November 2008 is when we began tracking presidential approval on a daily basis, using the same format and same religiosity questions we use today.

The overall approval ratings for these three presidents clearly are different at the particular points for which I've displayed the data. But the key here is the relative comparison of approval ratings for a president among those who are highly religious compared with those who are not -- regardless of the president's underlying overall rating. And, as can be seen, the difference in approval for Bush in late 2008 between those who are highly religious and those who are not religious (18 percentage points) is almost exactly the same as for Trump now (19 points). The gap for Obama in 2016 was 20 points, but in the opposite direction.

In this sense, Trump's advantage among the highly religious is about what we would expect for a Republican president.

Religiosity is of course highly related to partisanship. Highly religious Americans tend to skew Republican, while unreligious Americans tend to skew Democratic. Thus, we would expect that a good deal of the reason for the religion gap in presidential approval is directly related to these party factors. And that certainly appears to be the case.

When we isolate just Republicans, the religiosity effect for Trump disappears: 89% of highly religious Republicans approve of the job Trump is doing, compared with 87% of those who are moderately religious and 86% who are not religious. Among Democrats, approval is only four points different between those who are highly religious (11%) and those who are unreligious (7%).

Independents -- by definition -- are not as firmly anchored to a partisan affiliation. The religion gap among this group is thus a little larger, with 44% of highly religious independents approving, compared with 33% of nonreligious independents.

The same pattern existed for Obama and generally for Bush. The effect of religiosity is much less pronounced once partisanship is taken into account.

So Trump is doing better among those who are highly religious. This probably is less reflective of his personal religiousness or his specific policies than it is partisanship. Those who are highly religious tend to be Republicans, who in turn, of course, are very likely to approve of Trump. And Trump does worse among those who are nonreligious primarily because they tend to be Democrats.

These patterns are pretty baked into modern-day politics. I don't imagine they are going to change dramatically going forward. But that's why we continue to track job approval, and we'll see what develops as the Trump presidency unfolds.