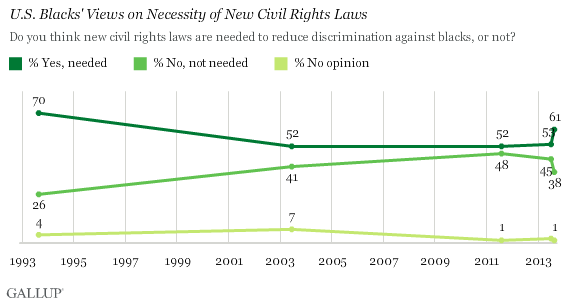

PRINCETON, NJ -- A month after Florida neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman was acquitted on all charges in the shooting death of a black teen named Trayvon Martin, blacks are more likely than they were just prior to the July 13 verdict to believe new civil rights laws are needed to reduce discrimination against blacks. An August Gallup poll finds 61% of blacks saying such laws are needed, up from 53% in a June-July poll.

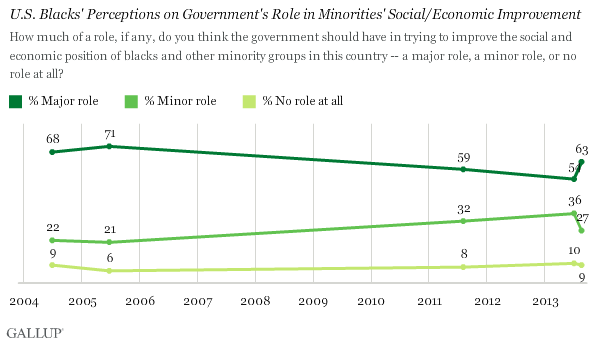

Blacks have also grown more likely to believe the government should have a "major role" in trying to improve the social and economic position of blacks and other minority groups in the country. Today's 63% is up from 54% in June-July.

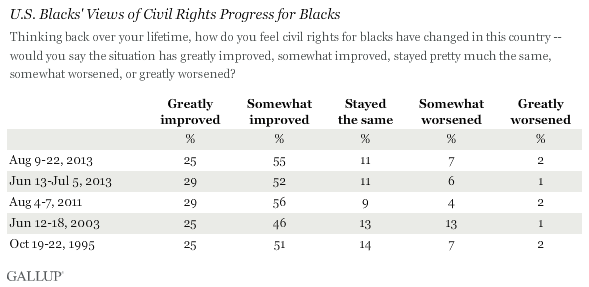

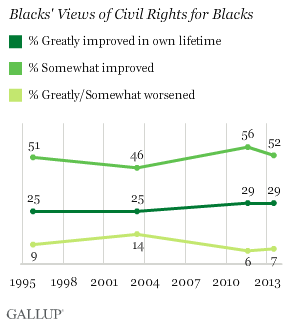

At the same time, blacks' views on the amount of progress that has been made during their lifetimes in advancing civil rights for blacks has changed little. Twenty-five percent now say the civil rights situation for blacks has greatly improved, and another 55% say it has somewhat improved. This compares with 29% saying greatly improved and 52% somewhat improved in the month just prior to the verdict.

The pre-Zimmerman-verdict results are from Gallup's 2013 Minority Rights and Relations poll, conducted June 13-July 5, 2013, and thus capture attitudes just before the verdict was delivered, but while the trial was in the news. This nationally representative survey of 4,373 adults, aged 18 and older, includes interviews with 2,149 non-Hispanic whites, 1,010 non-Hispanic blacks, and 1,000 Hispanics.

Gallup conducted the post-verdict survey Aug. 9-22 with a new sample of 1,001 non-Hispanic blacks, to gauge whether the decision had any sustained impact on how blacks view race relations in the U.S.

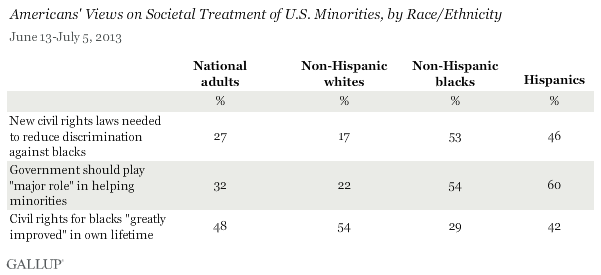

Blacks More Supportive Than Whites of an Active Government Role

Even before the solidifying of blacks' support for government action on civil rights seen since the Zimmerman verdict, Gallup recorded a sharp racial divide on these questions. In the June-July poll, 53% of blacks vs. 17% of whites believed new laws are needed to reduce discrimination. Similarly, 54% of blacks versus 22% of whites supported a major government role in improving minorities' economic and social status. By contrast, the majority of non-Hispanic whites versus 29% of blacks said civil rights for blacks have improved greatly over the course of their lifetimes.

Hispanics' views more closely align with blacks' views on the questions about government's ideal role in helping blacks and other minorities, but fall squarely between those of whites and blacks in their perceptions of civil rights progress.

Attitudes about how much progress has been made on civil rights for blacks are particularly relevant this year, given that Aug. 28 marks 50 years since Martin Luther King Jr. spoke on the National Mall about his dream for racial equality.

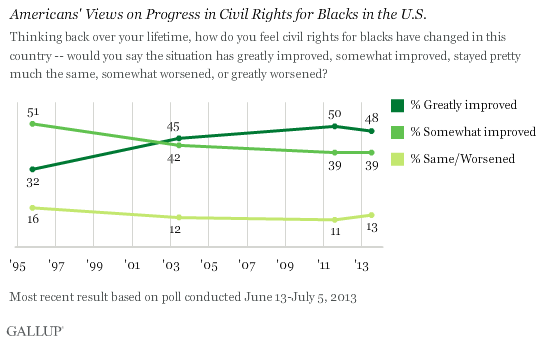

According to the June-July poll, close to half of Americans, 48%, believe civil rights for blacks have "greatly improved" over their lifetimes, and another 39% say they have somewhat improved. The percentage seeing great improvement rose significantly -- 13 percentage points -- between 1995 and 2003, and another five points between 2003 and 2011, before leveling off.

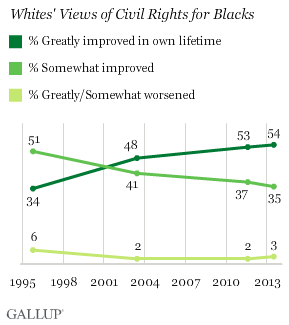

While the overall trend is positive, that is due almost entirely to a growing sense among whites that civil rights for blacks have improved. Barely a third of whites in October 1995 -- two weeks after that year's O.J. Simpson verdict -- thought civil rights had greatly improved, but that swelled to 48% by 2003 and reached the majority level in 2011, where it remains.

By contrast, the percentage of blacks perceiving great progress was at 25% in 1995, stayed at that level in 2003, and rose only slightly in 2011, halfway into President Barack Obama's first term, to 29%. As noted, this figure dipped slightly to 25% in August, after the Zimmerman verdict, although the change is not statistically significant.

Majority of Older Americans See Great Improvement

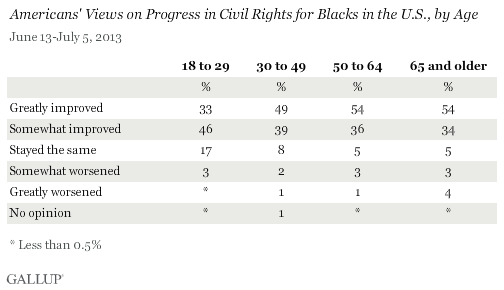

With some of the most significant legal advances in blacks' civil rights in the United States occurring in the 1950s and 1960s, it stands to reason that older Americans would be the most likely of all age groups to perceive major advances in racial equality. Nearly all of those aged 65 and older would have been born before President Harry Truman integrated the military by executive order in 1948, and might remember when the U.S. Supreme Court declared segregated schools unconstitutional in 1954. Accordingly, the slight majority of seniors, 54%, say the situation for blacks has improved greatly over their lifetimes.

Those aged 50 to 64 are just as likely as seniors to believe the cause of civil rights has made great strides during their lives. All in this group of baby boomers were born before President Lyndon Johnson signed the 1964 and 1968 Civil Rights Acts, as well as before congressional passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, and thus may have witnessed the transformative changes brought about by those landmark pieces of legislation. Many may also remember firsthand the contributions made by King, Malcolm X, Thurgood Marshall, Rosa Parks, Andrew Young, and other now-iconic names in the civil rights movement.

Americans younger than 50 are less likely to say civil rights have greatly improved. And 18- to 29-year-olds are significantly more likely than any other age category to say civil rights for blacks has stayed the same in their lifetimes. Seventeen percent of young adults say this, compared with no more than 8% of any of the older age groups.

Bottom Line

Americans broadly, as well as whites and blacks specifically, tend to believe that blacks' civil rights have improved in their lifetimes; relatively few say these have stayed the same or worsened. However, blacks are far less likely than whites to believe they have "greatly improved." In addition, possibly resulting from this, blacks are much more likely than whites to believe new civil rights laws are necessary, and to favor a major role for government in helping blacks and other minorities advance.

Even prior to the Zimmerman verdict, the majority of blacks thought the government should be doing more to battle discrimination and provide greater opportunity for blacks and other minorities. Thus, while the Zimmerman trial does not appear to have been a major watershed in altering blacks' views about civil rights in the U.S., Gallup polling a month afterward does find more blacks holding these positions. Future Gallup articles will discuss additional findings from the post-Zimmerman poll that focus on recent changes in blacks' views about U.S. black-white relations, as well as specific types of discrimination against blacks.

Survey Methods

Results for the June-July Gallup poll are based on telephone interviews conducted July 10-14, 2013, with a random sample of 2,027 adults, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

For results based on the total sample of national adults, one can say with 95% confidence that the margin of sampling error is ±3 percentage points.

For results based on sample of 2,149 non-Hispanic whites, the maximum margin of sampling error is ±3 percentage points.

For results based on sample of 1,010 non-Hispanic blacks, the maximum margin of sampling error is ±5 percentage points.

For results based on sample of 1,000 Hispanics, the maximum margin of sampling error is ±6 percentage points. (332 out of the 1,000 interviews with Hispanics were conducted in Spanish).

Interviews are conducted with respondents on landline telephones and cellular phones, with interviews conducted in Spanish for respondents who are primarily Spanish-speaking. Each sample of national adults includes a minimum quota of 50% cellphone respondents and 50% landline respondents, with additional minimum quotas by region. Landline and cell telephone numbers are selected using random-digit-dial methods. Landline respondents are chosen at random within each household on the basis of which member had the most recent birthday.

Samples are weighted to correct for unequal selection probability, nonresponse, and double coverage of landline and cell users in the two sampling frames. They are also weighted to match the national demographics of gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, region, population density, and phone status (cellphone only/landline only/both, and cellphone mostly). Demographic weighting targets are based on the March 2012 Current Population Survey figures for the aged 18 and older U.S. population. Phone status targets are based on the July-December 2011 National Health Interview Survey. Population density targets are based on the 2010 census. All reported margins of sampling error include the computed design effects for weighting.

Results for the August Gallup poll are based on telephone interviews conducted Aug. 9-22, 2013, with a random sample of 1,001 blacks, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

For results based on the total sample of blacks, one can say with 95% confidence that the margin of sampling error is ±4 percentage points.

All respondents were initially interviewed as part of Gallup Daily tracking and re-interviewed for this study.

Gallup Daily tracking Samples are weighted to correct for unequal selection probability, nonresponse, and double coverage of landline and cell users in the two sampling frames. They are also weighted to match the national demographics of gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, region, population density, and phone status (cellphone only/landline only/both, cellphone mostly, and having an unlisted landline number). Demographic weighting targets are based on the March 2012 Current Population Survey figures for the aged 18 and older U.S. population. Phone status targets are based on the July-December 2011 National Health Interview Survey. Population density targets are based on the 2010 census. All reported margins of sampling error include the computed design effects for weighting.

The obtained sample of re-contacts was weighted to match census demographics for blacks on gender, age, education and region.

In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

View methodology, full question results, and trend data.

For more details on Gallup's polling methodology, visit www.gallup.com.