This article is part of a weeklong series focusing on how people worldwide answer some of today's most pressing questions about employment and the economy.

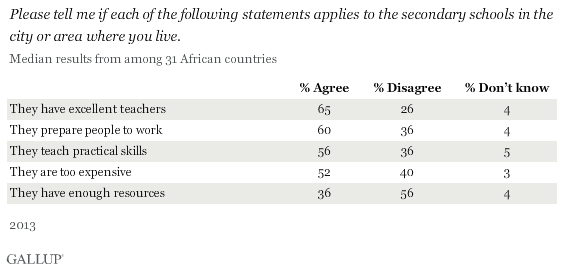

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- Many African countries have made great strides toward achieving universal primary education, but there is still a significant need continent-wide for more access to secondary education. Africans themselves are mixed about the secondary schools in their communities. Median results from the 31 countries surveyed in 2013 show that most residents feel the secondary schools in their area have excellent teachers (65%), prepare people to work (60%), and teach practical skills (56%). However, majorities don't feel secondary schools have enough resources (56%) and that they are too expensive (52%).

The World Bank has long recognized that the expansion and improvement of secondary education should be a developmental priority in Africa. In 2003, the Bank launched its Secondary Education in Africa project to help countries develop strategies and build partnerships to address that priority; as project's 2008 report noted, "expanded access to and improved quality of secondary education in sub-Saharan Africa are key ingredients for economic growth in the region."

So far, however, secondary education remains much rarer than primary education across the continent. In many areas, funding for infrastructure has been hard to come by, and residents are often unable to pay fees to support their local secondary schools. There are also demand constraints -- for many Africans, sending their older children to school represents a huge sacrifice, as they are better able than primary-school-aged children to help with farm work or other means of supporting their families.

Perceived Cost and Benefits of Secondary School Vary Widely by Country

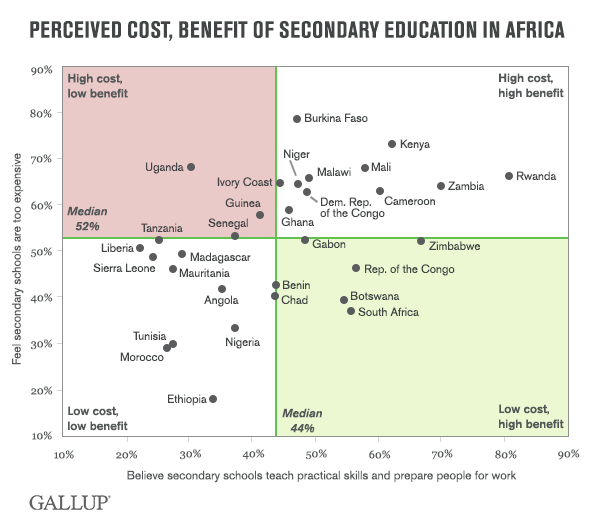

Africans' calculations of costs vs. benefits is a key consideration for countries seeking to boost development through secondary education. To the extent that residents feel the practical benefits of such an education are high relative to the cost, they will be more likely to make the sacrifices necessary to ensure their children attend and succeed in secondary school.

The graph plots the perception that secondary schools are beneficial -- by teaching practical skills and preparing people for work -- against the view that they are too costly in each of these 31 countries. Among the countries in the lower right quadrant, the first view -- that secondary schools are beneficial -- is relatively widespread, while the second -- that they are too expensive -- is not. This suggests residents' cost/benefit calculation would be more likely to support high participation in secondary education.

Among countries in the upper left quadrant, the reverse is true; residents are relatively likely to say secondary school is too expensive, but less likely to feel it is beneficial. However, most countries fall into the other two quadrants: residents see secondary education as costly but also beneficial (upper right), or they feel it is neither (lower left).

Results from each country provide useful information for experts and policymakers about the success, or potential success, of secondary education improvement programs. Uganda, for example, became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to introduce universal secondary education in 2007 -- but in 2013, just 31% of Ugandans felt their local secondary schools taught practical skills and prepared people for work, while 68% said they were too expensive. These figures point to widespread frustration with the country's difficulties in maintaining education quality standards as access has expanded.

Resources Linked to Satisfaction With Local Education

While the expense of a secondary education weighs heavily on many Africans' minds, their perception that secondary schools have enough resources is the one most closely related to their satisfaction with their local schools more generally.

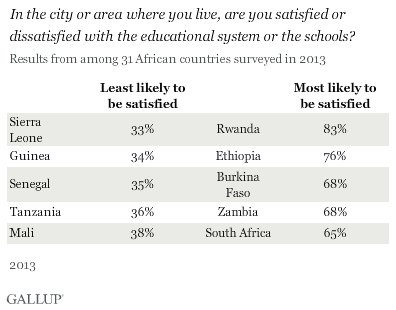

Africans are mixed on this subject as well, with more than half of residents (54%) saying they are satisfied with the schools in their area, while 44% are dissatisfied. However, results also vary widely by country, from a low of about one-third satisfied in Senegal, Guinea, and Sierra Leone to more than three-fourths satisfied in Rwanda, Ethiopia, Burkina Faso, and Zambia.

Bottom Line

Gallup has previously found that rates of poverty and hardship drop substantially among Africans with a secondary education or more. One reason is that, if secondary schools are performing effectively, they help prepare students who are nearing adulthood to meet the needs of their country's labor market. Africans with a secondary education are twice as likely as those without to work full time for an employer (16% vs. 8%, respectively).

However, students and parents need to be engaged for secondary education systems to succeed. Otherwise, attendance rates are likely to remain low, muting the effect post-primary schools have on Africans' lives and their countries' economic growth. In many countries, however, building such engagement will require changing residents' perceptions about the value of secondary education, the costs associated with it, or both.

The data on satisfaction with the educational system in this article were generated from Gallup Analytics. For complete data sets or custom research from the more than 150 countries Gallup continually surveys, please contact us.

Survey Methods

Results are based on approximately 1,000 face-to-face interviews with adults, aged 15 and older, in each country during 2013. For results based on the total sample of national adults, one can say with 95% confidence that the margin of error is approximately ±3.9 percentage points and reflects the influence of stratification and clustering. The margin of error reflects the influence of data weighting. In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

For more complete methodology and specific survey dates, please review Gallup's Country Data Set details.