Most companies' pricing strategies are based on four things: what the competition is doing, what the market will bear, cost plus, and some estimation of the value that the customer receives. In the best of times, pricing strategies are often based more on art than science, and these are surely not the best of times.

|

The U.S. Producer Price Index for Finished Goods has been inching up a point or so every month this year since May. The U.S. Consumer Price Index for July 2008 is up 5.6% over the previous year, driven by big increases in energy and transportation. And consumer spending is down. An August Gallup Poll found that Americans say the economy is the country's most important problem -- for the seventh month in a row prices. (See graphic "Most Important Problem in the United States" and "Conditions Ripe for a Midsummer Night's Headache" in the "See Also" area on this page.)

|

That makes setting pricing strategies even more challenging in a down economy. If you aren't sure you're getting the most out of your prices when times are flush, how do you know what to charge when consumers are reluctant to buy at all? How do you protect your margins while keeping your customers? And is it even possible to build your customer base in times like these?

It may be difficult to come up with solid pricing formulas in a tough economy, but it's not impossible. Now more than ever, businesses must understand the psychology of their customers.

Not all choices are good ones

"All companies have different price structures, and if you can be the company that doesn't raise prices, that would seem to be a competitive advantage," says William J. McEwen, Ph.D., global practice leader for Gallup's brand performance management practice and author of Married to the Brand. "But it might knock the hell out of your ability to compete in other ways."

When companies are considering their ability to compete, they may have to choose between losing profitability or losing customers. That's not a bad problem to have -- if your company is healthy enough to consider taking a hit to its margins, it's probably healthier than most. Even so, shaving prices is a short-term solution, and the inflationary, perhaps recessionary, economy may be a long-term problem.

Some companies may be looking for more subtle solutions. One possibility is to reduce production costs by cutting corners on materials or personnel. Another is to downsize the amount of product in the package, but not the price. "Some manufacturers choose to do this either because they think consumers won't notice or because they think people would prefer to get a little bit less at the same price than pay more for the same amount they used to get," says John T. Gourville, Ph.D., a professor in the marketing unit at Harvard Business School.

Even when the reduced production methods are completely aboveboard -- such as reducing the amount of ice cream in the tub, but not the price, when the weight by volume is clearly marked on the label -- customers may still take offense. "One of our CE11 [Gallup's customer engagement assessment] measures has to do with 'treating me fairly,' and I think 'fairly' is in accord with 'what seems reasonable,'" says McEwen.

It may seem reasonable to the company to put less ice cream in the tub. Some customers won't care, and others won't notice the difference. Other customers, however, may feel somewhat cheated by paying the same and getting less. As McEwen points out, customers who feel like they're being treated unfairly can easily become customers who are willing to try a competitor.

It's all in the timing

If your company can't cut production costs or reduce content, and if profitability is at stake, the only option left may be to raise prices. But there are ways to approach a price increase that reduce the risk of alienating customers. "What you charge is important," says Gourville, "but so is how you charge."

|

Delayed payment plans, such as installment payments or credit, can make consumers feel better about their purchase. "Think about a transaction as having a pain component -- the paying, and a pleasure component -- the getting. The further you can push out the pain, the more attractive the deal seems to be," says Gourville. The automobile financing industry -- in fact, much of the automobile industry itself -- is funded on this principle.

However, this tactic doesn't always work. For instance, as Gourville's research shows, consumers react differently to prices depending on when they use what they buy. "People would like to match their consumption to their payments," he says. "We would prefer not to be paying for things that we've already consumed. We'd like to be spending and consuming at about the same rate, which is why the leasing of cars is a palatable transaction." But for big-ticket items that are consumed immediately -- pricey vacations, for instance -- spreading payments out after consumption makes the purchase less appealing.

Consumers are also more likely to feel like they're getting their money's worth from a purchase when the memory of the payment is fresh. That's why health club members tend to spend more time in the gym when they pay monthly rather than annual fees -- the "pain" of the cost is more vivid, and they want to get what they paid for. If the monthly cost seems small, and the cost seems to have recently matched the purchase, people are more likely to continue buying. This is an important concept to bear in mind when considering pricing strategies that involve annual renewals.

Understanding how people feel about buying things from you can go a long way toward getting them to keep doing it. Just make sure your strategy is sustainable long term. This is where so many mortgage lenders wandered into dangerous territory. "When you think about how you sell in tough times, you've got to be willing to get creative in finding a mechanism for people to buy the products you want to sell them," says Gourville. "At the same time, it doesn't do anybody any favors to have people default on those payments. You want payments -- if you're [a] good and ethical [business] -- to be something that customers will actually carry through on."

Honesty is the best policy

Many times, companies must raise prices on products that can't be sold on a payment plan. It can be done without riling the marketplace, though, if it's handled well. "I think a lot of companies are scared to death that their competitors will find out how they operate. That's approaching pricing as an internal consideration rather than as a customer communication consideration," says McEwen. "The way your company explains pricing can be an excellent point of differentiation -- but you do have to explain it the right way."

Start by refusing to underestimate the intelligence of the consumer. "There are ways to explain price increases that companies haven't pursued because they feel they need to hide the price hike. But I think people understand that prices are going up," McEwen says.

Both McEwen and Gourville cite the airline industry as a perfect example of how to communicate price hikes badly. McEwen calls the new bag storage fee "a crummy idea," and Gourville calls it "ludicrous" because consumers don't feel that the cost has anything to do with operating the aircraft -- so it's perceived as unfair.

A plainly stated fuel surcharge, however, would seem less like price gouging because consumers realize the cost of gas is rising, which naturally affects operation costs. "That's not just a blanket price increase; it's a price increase for a reason and a reason we can, in a sense, justify," says Gourville. "Fees that are explainable are much more tolerable than fees that seem to crop up out of nowhere."

Procter & Gamble, in contrast, may be tackling the challenge well. Recently, the company announced a 16% price hike, even though it's in a crowded market. "P&G said that they aren't raising prices in anticipation of cost increases; they're only raising prices in response to cost increases," says Gourville. "I think people will accept that."

Though the baggage surcharge won't raise overall prices for airlines as much as Procter & Gamble's increases will, the latter change will probably infuriate fewer customers. Consumers know and understand why shaving cream has to cost more now and can't blame P&G for trying to stay in the black. It's a cost increase, but it's both honest and transparent.

|

"Transparency seems to be a very hot topic, discussed by companies and apparently expected by consumers," says McEwen. "Transparency involves straight talk and sincerity, key requirements in any reciprocal relationship. This may be increasingly important in an age when consumers have grown skeptical about promises that are made but not kept -- and skeptical about the hidden agendas of the companies who market products and services."

If companies hold their transparency card close to their vest, consumers may respond by keeping a tight grip on their loyalty card. "When either the economy or your business tanks, the appropriate response is not to compromise ethical principles. It is to reaffirm them," notes entrepreneur Clinton Korver, founder and CEO of DecisionStreet. "While scary during tough times, truthfulness and transparency are always a winning strategy. Doing the right thing when you're tempted not to sends a powerful and long-lasting message." (See "Why Ethics Matter in a Downturn" in the "See Also" area on this page.)

Customer engagement: dead or disguised?

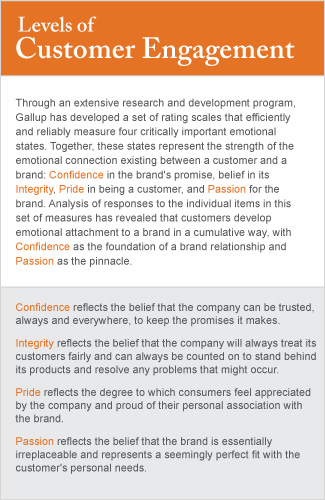

Enduring relationships are reciprocal, not one-way. And reciprocal relationships are the heart of customer engagement, the powerful emotional attachment people can develop for brands or businesses. Gallup research shows that customer engagement is based on the strength of four basic emotional needs: confidence in the company/brand, belief that the company has integrity, pride in association with the company/brand, and passion for the brand. (See graphic "Levels of Customer Engagement.")

When times are tough, brand loyalty is much harder to come by, discretionary purchases go down, and people are more price sensitive, according to Gourville. But  companies will hold on to their engaged customers if they maintain a reciprocal relationship and don't hold back on providing for those four needs.

companies will hold on to their engaged customers if they maintain a reciprocal relationship and don't hold back on providing for those four needs.

Businesses must keep up their end of the relationship concerning prices: Don't betray the brand promise or try to trick consumers; raise prices if you must, or drop amenities as long as they're irrelevant to the market, as Southwest Airlines did with meal service. And if you really don't know what the consumer base will tolerate, ask.

"Companies need to provide solid evidence that they're listening and that they're responding in recognition of their customers' evident needs. This can be done by providing options, perhaps as a 'menu' approach that lets customers decide what they want -- and what they're willing to pay for," says McEwen. "If companies can show they're listening to their customers and convincingly convey a sense of mutual commitment to weather the tough times together, then there's a real chance that these relationships will endure."

During times like these, businesses need all the engaged customers they can get. According to Gallup research, engaged customers are more loyal, return more often, are passionate advocates, and spend significantly more. At one credit card company, engaged customers used their cards 45% more often and spent 78% more with them than did disengaged customers. The engaged customers of a luxury retailer spent 44% more than its disengaged customers did. And a global cargo shipper's engaged customers gave the company 39% of their total business versus 22% among the non-engaged customers. In general, engaged customers represent a 23% premium, and disengaged customers represent a 13% discount to the businesses they use.

Smart pricing

Eventually, the economy will right itself, and consumers will stop seeing every price tag as a threat. The companies that live to see that day are the ones that work smarter now -- and part of being smart is knowing how to price. As Gourville notes, "The question is, how do you make sure that you continue to be one of those products that people buy?"

The answer is to be worth the right price. And the right price is, apparently, the one that's offered the right way, feels fair to consumers, keeps a healthy balance sheet, and maintains customers' and businesses' integrity.