The specter of employee disengagement is haunting the German economy. Just 15% of workers in Germany are engaged with their jobs, while 61% are not engaged and 24% are actively disengaged, according to Gallup Daily tracking. This doesn't bode well for the health of the German economy. Gallup estimates that actively disengaged employees cost the economy between 112 billion and 138 billion euros per year in lost productivity.

Engagement brings many positive benefits to businesses, including higher profitability, productivity, and customer ratings as well as reductions in turnover, safety incidents, shrinkage, absenteeism, and quality defects.

Engagement brings many positive benefits to businesses, including higher profitability, productivity, and customer ratings as well as reductions in turnover, safety incidents, shrinkage, absenteeism, and quality defects.

Engaged workers also are more innovative and have more and better ideas: Seven in 10 engaged employees had an idea for improving their company in the last 12 months, compared with four in 10 actively disengaged employees. About half of engaged employees report that their idea has been implemented. When asked whether their idea led to cost savings, increased revenue, or increased efficiency for their company or organization, nine in 10 engaged employees answered yes, compared with only three in 10 actively disengaged employees.

If only 15% of Germany's employees are engaged, most of the country's workers are a long way from maximizing their potential. What's more, the 24% of employees who are actively disengaged are emotionally disconnected from their work and workplace; they are less likely to put in discretionary effort, and they jeopardize the performance of their colleagues.

Particularly worrisome is that the trend shows no sign of improvement. Gallup's analysis reveals that the percentage of German employees who are engaged is roughly the same now as it was in the past. But the percentage of actively disengaged employees has increased from 15% in 2001 to 24% in 2012 -- indicating a deterioration of the working environment due to poorer management. (See graphic "Active Disengagement and Lost Productivity Are Harming the German Economy.")

Older workers feel neglected

The increase in the percentage of actively disengaged employees may be related to ongoing demographic changes in the German workforce. The proportion of older workers -- those aged 50 and up -- has increased from 21% in 2001 to almost 29% in 2011, while the proportion of younger workers has been shrinking. In some industries, there is already a shortage of skilled workers. The German economy and German businesses need these older workers to remain active and engaged in the workplace because in the immediate future, there will be fewer and fewer younger workers to replace them.

German management education pays little attention to actually managing people.

Yet it seems that engagement is slipping among this key group of workers. The percentage of actively disengaged employees is highest among older workers (29%) compared with 23% actively disengaged among Generation X workers (those born between 1965 and 1979) and 23% among Generation Y workers (those born between 1980 and 1995).

The older generation of workers feels neglected, Gallup analysis shows. Key drivers of employee engagement -- such as feedback from supervisors, encouraging development, opportunities to learn and grow, and feeling cared for -- are significantly less fulfilled among older workers when compared with younger employees. In spite of older workers' crucial importance to the country's economy, they seem to be disappearing from management's radar. Business leaders and managers need to focus their attention on the needs of these employees to help them become engaged and active contributors in the workplace.

Managers play an essential role

German companies must get a handle on this negative development. If more and more employees fail to bring their best effort to work every day -- regardless of what generation they belong to -- it's because companies are failing to create a culture that meets employees' needs and expectations.

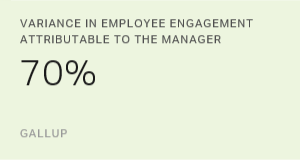

Businesses must understand the key role managers play in increasing engagement by addressing employees' most crucial needs and expectations. In fact, the most important decision a company's leadership makes is who it names as managers.

Because of this, companies should investigate the criteria they use to promote people in their organization and closely evaluate how effectively their managers motivate and inspire people. Companies also must recognize that building employee engagement takes talent, and promoting people who lack the talent to manage hurts workers, companies, and profits.

A key problem is that German management education pays little attention to actually managing people. The "master of business administration" degree reflects that the educational emphasis is on managing finances and administrating processes. But good management also requires a focus on people, something that German companies currently lack. In far too many businesses, employees with the longest tenure or who have the greatest subject matter expertise are moved into management, regardless of whether they have an aptitude for managing people.

As a result, the talent for managing people is more of an accidental dividend among German managers than a desired characteristic. Managers who can engage their workers will build better, more profitable teams -- but companies that don't understand that talent and don't look for it won't successfully recruit engaging managers. By ignoring the benefits of engagement and the talents of engaging managers, German companies will continue to leave their financial well-being to chance.

Results are based on telephone interviews conducted between August 1 and December 21, 2012, with a random sample of 2,198 workers, aged 18 and older, living in Germany. Interviews are conducted with respondents on landline telephones and cellular phones. For results based on the total sample of workers, one can say with 95% confidence that the maximum margin of sampling error is ±2.9 percentage points. Margins of sampling errors vary for individual subsamples. In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.