The almost completely partisan Senate vote on the Supreme Court nomination of Brett Kavanaugh underscores the frequent lack of compromise among our elected representatives in Washington. One Democratic senator voted for Kavanaugh, and one Republican senator voted against Kavanaugh. Otherwise, every elected representative voted their party line.

Senators themselves have bemoaned this hyper-partisanship as another example of a dysfunctional Congress. The New York Times reported the comments of Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois, Democrat: "I have seen this institution change so dramatically in the 20 years I have been here. Fundamentals, debate on the floor. That used to be the hallmark of this institution, but now it is virtually unheard-of to have a controversial amendment. Both sides are to blame," and quoted Senator Richard Shelby of Alabama, Republican, on the Kavanaugh situation, "It has not been good for the Senate, none of this. Too much estrangement on both sides."

The Importance of Compromise to the U.S. Public

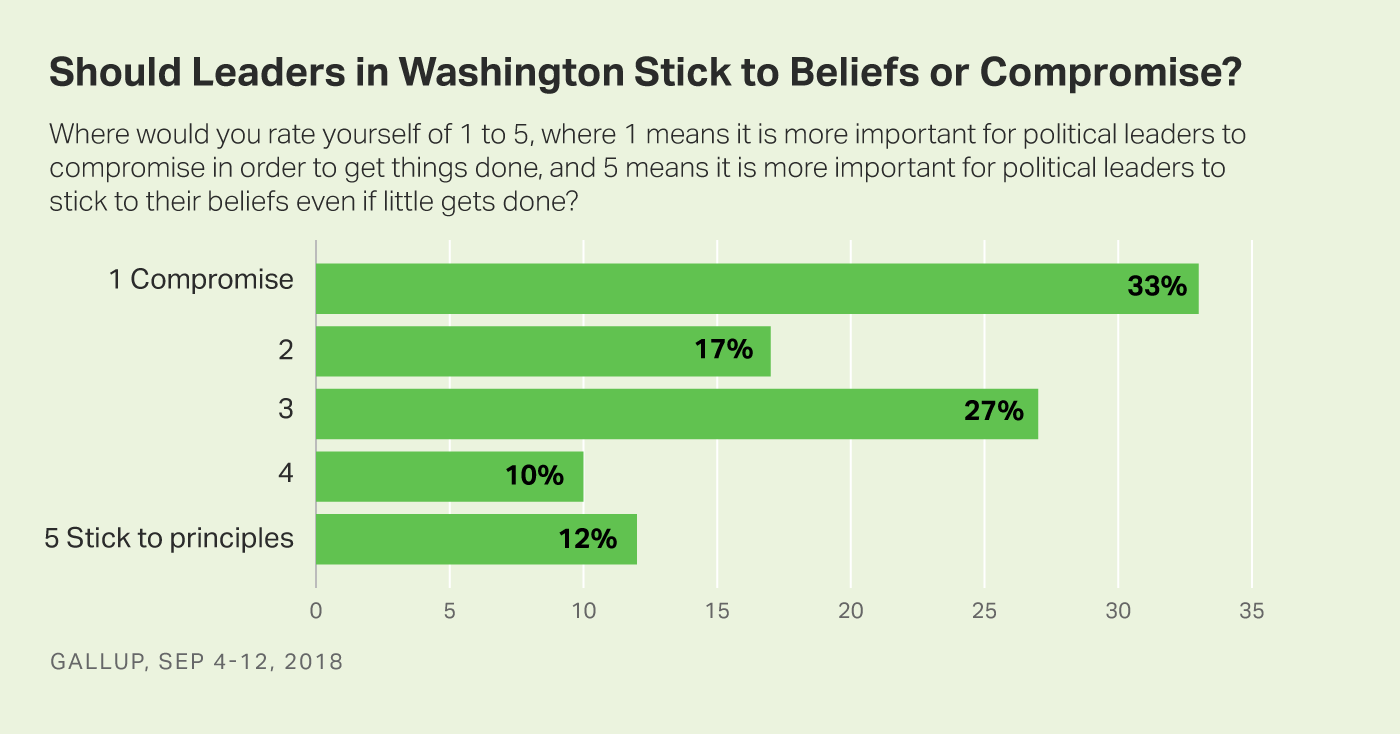

For years, Gallup has been asking Americans to place themselves on a 1 to 5 scale, anchored at one end with the idea that "It is more important for political leaders to compromise in order to get things done" and anchored at the other end with "It is more important for political leaders to stick to their beliefs even if little gets done."

Given these choices, Americans have consistently tilted toward the compromise end of the spectrum. In our most recent update, 22% of Americans chose the two points at the end of the scale representing sticking to principle, while 50% were at the compromise end of the scale. Another 27% were in the middle, neutral position.

This basic preference for political leaders to compromise rather than stick to principle has prevailed every time the question has been asked since 2010.

Of course, we need to keep in mind that a stated desire for compromise may sound good to many people -- but that conviction could crumble once the reality of actual negotiating sets in. As cynics point out, people may believe it is great to compromise as long as it is those on the other side who do the compromising. Still, at least in theory, the data are pretty clear that Americans tilt toward the compromise end of the spectrum.

Compromise as a Remedy for Americans' Poor View of Congress

Congressional approval is now at 19%. Americans rate the honesty and ethics of members of Congress near the bottom of a long list of professions measured. The federal government is rated more negatively than any of 24 other business and industry entities tested. Less than four in 10 Americans are satisfied with the way the nation is being governed. We have seen an uptick in confidence in the legislative branch recently because Republicans are more positive, perhaps specifically because Republicans in Congress are not compromising. But a dysfunctional government remains, month after month, Americans' pick as the number one problem facing the nation. Obviously, the people taken as a whole want change in Washington.

And the data on compromise support the proposition that the people of the country, at least in theory, believe it would be better for Congress -- and for the nation -- if there were not as many rigid ideologues elected to Congress, and more people elected who were willing to give in order to find the best solution.

What happens when elected representatives who refuse to compromise dominate Congress? Congressional policy actions essentially revert to a strictly mathematical counting of heads. That is, assuming that rigid representatives will not compromise or discuss modifications in their underlying beliefs, simple votes will determine which side wins, in a win-lose type of situation. This is what we saw play out in the Kavanaugh process. This lessens the possible positive impact of many of the historical functions Congress is supposed to undertake -- hearings with experts, testimony, reports from committees and the classic debate and deliberation as envisioned by the Founders. If ideologues come to Washington with their minds made up and their agendas rigidly set, then Congress basically becomes a vote counting function, and much of the rest of the congressional process could be dismantled.

Additionally, representatives should be open to the collective wisdom of all the people and should take into account the broad concerns of the entire population, not just those who elected them. Sticking rigidly to prior principles makes this less likely.

Why Do Uncompromising Members of Congress Get Re-Elected?

The reasons why rigid representatives continue to get elected despite the stated wishes of the people for less rigid representation are complex. Explanations center on redistricting, political sorting of voters into homogenous districts and states, the enormous influence of money from entities who demand elected representatives stick to certain policy courses of action, elections in which small numbers of voters in primaries essentially determine the winner of the general election, and the impact of politically differentiated news media.

Structural changes focused on redistricting and campaign finance reform could be effective in producing less rigidity and more compromise. Various entities are attempting to bring these types of changes about, with varying levels of success.

An additional remedy for the lack of compromise in Congress would be higher voter turnout. Estimates are that less than 37% of the voting-eligible population turned out to vote in the last midterm election in 2014, and midterm turnout is routinely at or around the 40% level.

In many cases, an even smaller percentage of eligible voters are responsible for electing representatives, given that the winner of the primary in dominantly red or blue districts and states goes on to win the general election by default. And turnout in primaries is even lower than turnout in general elections. The minority of possible voters who favor more extreme ideologies and would favor candidates who stick rigidly to principles can be disproportionately influential in the outcomes in these situations. Low turnout also helps deep pocket organizations, businesses and political parties more easily influence the election outcome -- and these entities often extract policy promises from candidates that do not include the idea of compromise.

Another way to bring about more compromise in Congress would be to introduce viable candidates from third or independent parties, who presumably would be less under the influence of party platforms, party bosses and specific ideologies. Gallup data show there is an appetite for third parties. At our latest asking, 57% of Americans say that the Republican and Democratic parties are doing such a poor job that a third major party is needed. Majority approval for the idea of a third party has been consistent over the past five years.

Of course, running viable candidates outside of the existing Republican and Democratic structures is very difficult. Even billionaire Michael Bloomberg, who is considering a run for president, has decided that he can't do it as an independent and instead would need to run -- if he does -- as a Democrat in 2020. According to a New York Times report, Bloomberg said the he "now firmly believes only a major-party nominee can win the White House."

But independent or third party candidates, if elected, might be in unique positions to broker compromises and produce more of the deliberative function the people desire.

There is also the idea of a new "compromise" movement, analogous in structure to the Tea Party movement. The idea would be to champion the election of compromisers and non-rigid ideologues to Congress. The probability of success of such a movement is not high since rigid, ideologically fixated candidates are more likely to evoke emotions and hence participation than the less exciting idea of middle-of-the-road compromise. The success of such a compromise movement would depend on leadership, as is almost always the case with social movements in our society.

Bringing about any change in the way the government operates is tough. Some individuals and entities like the idea of rigidly ideological elected representatives, either on philosophic, or more likely, practical grounds. But the American public, taken as a whole, clearly wants more compromise out of those people that represent them, and ultimately the pendulum may swing back to favor people who more closely fulfill the Founders' idea of how our representative democracy should work.