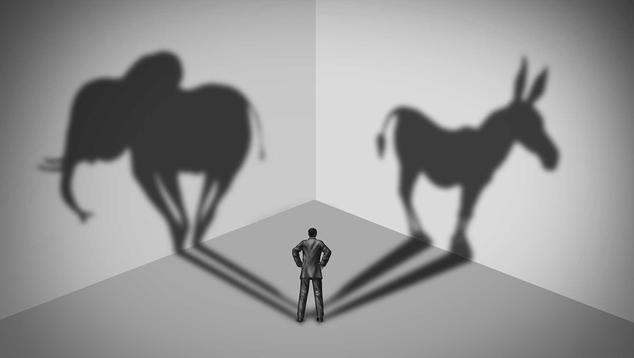

One of the defining characteristics of our age is emotional partisanship, when Americans' political and ideological self-identities are so emotionally powerful that they become the lens through which Americans view many nonpolitical aspects of their lives.

As I've written recently, the results of identifying strongly with a tribe reflect an inherent human desire for social solidarity. As we saw in Sebastian Junger's fascinating book Tribe, there is great power in being part of a close-knit group with a common purpose and common threats. This, according to Junger, helps explain why military veterans miss combat and reenlist to go back to war zones, and why in U.S. history settlers captured by Native Americans infrequently wanted to leave those tribes and go home (and why few Native Americans fled their tribes to join settlers).

We have fewer opportunities for such real-world, in-person group solidarity these days (for a variety of reasons). Our political identity can thus increasingly become our tribal identity (even if most of the identifying comes about remotely). This process is aided and abetted by people and entities who benefit from tribalism, including media outlets eager for ratings and politicians eager for primary votes.

As noted, as our political identity becomes a dominant part of our self-identity, it can evolve into the dominant framework through which we view and evaluate what's going on around us. This happens in part because the intense emotions that many Americans attach to their political identity are extraordinarily powerful. Recent research shows, for example, that people can adjust race, ethnicity, sexual identity and class labels to fit with their political identity.

Political identity is so powerful, it appears, that it can even result in changes in the way we view our religious lives. Dr. Michele Margolis of the University of Pennsylvania posits that one explanation for the well-known connection between politics and religiosity in the U.S. today is the tendency to adjust the latter to fit the former (as is evident from the title of her award-winning book, From Politics to the Pews). Margolis is careful to note that this relationship is complex. But her research emphasizes that for some people, rather than picking a political identity to fit with their underlying religion and religious identity, they choose a religious identity and level of religiosity that fits with their underlying (and powerful) political identity.

One might think that Americans assess the economy based on what they hear and read about the stock market, unemployment and indications of business vitality. But a persistent finding is that Americans' views of the economy are substantially affected by their underlying political identity. When a president of a different political party takes over the White House, as has happened most recently in 2000, 2008 and 2016, Republicans' and Democrats' assessments of the economy change essentially overnight. In 2017, for example, it became cognitively inconsistent for Democrats to believe that the economy was getting better and in good shape with a Republican president in charge, so their positive views of the economy plummeted. Republicans suddenly became much more positive about the economy. As my colleague Andrew Dugan noted in his analysis of 2017 Gallup data, "Republicans' confidence in the economy stood at +46 in 2017, a 77-point improvement from 2016."

The point here is that our political identity -- which in today's environment often centers on views of President Donald Trump -- is a central lens in how we see the rest of the world. Humans seek cognitive consistency. If our political identity, bolstered by emotional connections, is our primary underlying self-identity, then we will adjust many of our attitudes and views to be cognitively consistent with that political identity.

Healthcare Is No Exception

All of this brings us to healthcare, one of the most important problems facing the nation according to the American public -- and certainly an issue prompting as much heated political debate as any other on the country's agenda. Several articles analyzing public opinion on healthcare published by my Gallup colleagues in recent weeks have shown the significant power of political identity in Americans' assessments of both national healthcare and in evaluations of their own healthcare situation.

We would expect to see highly partisan reactions when we ask Americans for their opinions of overtly political aspects of healthcare -- and we do. Democrats are much more positive about the Affordable Care Act than are Republicans. Recent Kaiser Family Foundation research shows Republicans are much less positive about "Medicare for All." There are also sharp partisan differences in views of the desired role of government in the nation's healthcare. We find highly partisan differences in general views of healthcare costs in the U.S. and in perceptions of whether the nation's healthcare system is in a crisis. Democrats are much more negative than Republicans on both of these dimensions.

The most fascinating findings, however, focus on the degree to which we also see big differences by partisanship in attitudes toward personal healthcare. This includes how Americans view their health insurance coverage, their healthcare costs and the quality of their healthcare -- as well as reports of having delayed medical treatment due to costs, and even self-reports of having a preexisting medical condition. On all of these dimensions, Democrats report more negative assessments than do Republicans.

A number of these attitudes became more positive among Republicans once Trump took office, and became more negative among Democrats. On the issue of deferring medical treatment because of costs, for example, my colleague Lydia Saad recently reported that "most of the recent increase in reports that family members are delaying treatment for serious conditions has occurred among self-identified Democrats."

It's doubtful that the reality of Americans' personal healthcare situations changed overnight. What changed is the party in power, and thus the party presumably positioned to receive more of the reflected glory from positive healthcare conditions in the country.

Trump took office focusing on scaling back government involvement in healthcare and criticizing the Affordable Care Act. Democratic leaders (and presidential candidates, more recently) have been emphasizing the troubled aspects of the nation's healthcare systems and the need for radical improvements. Thus, Americans who identify as Democrats follow these cues and find it more difficult to assess their healthcare situation positively, while Republicans have the opposite reaction.

Political Identity Associated With Underlying Emotional State

Our underlying emotions, centered on a strong attachment to our political identity, can clearly drive the way our more rational self organizes, sees and reacts to the world around us. Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls these underlying parts of the mind "System 1" and "System 2" in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow. System 1 "operates automatically and quickly with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control," while System 2 "allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations."

Our political identity, I think, tends to be associated with the System 1 side of our brains, as an involuntary, organizing principle that guides System 2 thinking when we are called on to produce self-assessments. When asked about healthcare, our underlying political identity provides the context for our rational self to respond. If Republican thought leaders, for example, are publicly opposed to the need for public intervention in health systems and Medicare for All (with the concomitant thought that the healthcare system is working well without the need for these changes), then these positions become integrated into political identity and dominate when rank-and-file Republicans are asked questions about healthcare -- both at the national level and when assessing their personal health situation. Democrats' underlying identities push them to view healthcare in a way consistent with the negative assessments put forth by Democratic thought leaders.

The idea that partisans follow the cues of their political leaders in forming attitudes about policy issues is not new, of course. But the recent accumulation of evidence on the powerful and widespread effect of emotional partisanship on so many aspects of the ways Americans think about their personal lives underscores how hard it is becoming to change policy attitudes. It's difficult to quickly adjust our thinking about healthcare issues unless there is evidence that such adjustments would be consistent with changes in our political identity. This is presumably true regardless of the reality of what we experience related to healthcare at either the national or personal level.

Bottom Line

We might assume that Americans' views on policy issues are the result of many complex forces, including personal experience. In terms of healthcare, this could mean that views on health policy could reflect Americans' own personal healthcare situations. But if our underlying political identity is increasingly likely to be the driving force behind our assessments of all things health-related -- including seemingly factual, personal aspects -- it's going to be more difficult to produce significant shifts in public sentiment. "Direct to the consumer" appeals to change attitudes on healthcare policy based solely on rational assessments of data and evidence may be less effective unless: a) Americans' underlying political identity changes, or b) the thought leaders of their political tribe give them cues that it is OK to adopt new attitudes.