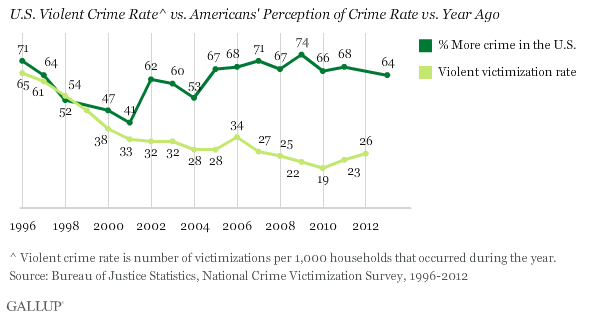

PRINCETON, NJ -- The U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics recently released its crime figures for 2012, showing the rate of violent crimes in the U.S. increasing for the second consecutive year. Victimizations per thousand rose from 19 in 2010 to 23 in 2011 and 26 in 2012. Nevertheless, slightly fewer Americans today than in 2011 -- 64% vs. 68% -- believe crime in general is up over a year ago.

The latest figures come from Gallup's annual Crime survey, conducted Oct. 3-6.

Serious crime in the U.S. began to fall in the mid-1990s and continued downward through 2010, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. Americans initially appeared to recognize the positive trend, with the drop in the violent crime rate between 1996 and 2001 -- from 65 victimizations per 1,000 to 33 -- coinciding with a sharp drop in the percentage saying crime was up.

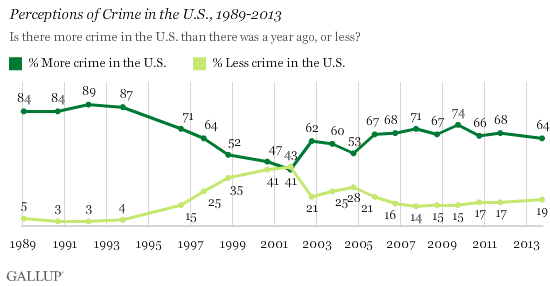

The public was most positive in October 2001, just one month after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, when 41% believed there was more crime in the U.S., and 43% said there was less. These attitudes changed dramatically the next year -- most likely related to the 2002 Washington, D.C.,-area sniper shootings that were still occurring at the time of the poll. The proportion of Americans who perceived that crime was worse jumped to 62% that year, and was consistently 66% or higher from 2005 to 2011.

Now, despite the setback in battling crime in the past two years, Americans are slightly more, rather than less, positive about the crime rate. The majority do say there has been more crime, but because the majority almost always say this, the relative percentage is more important.

Concern About Local Crime Also Down

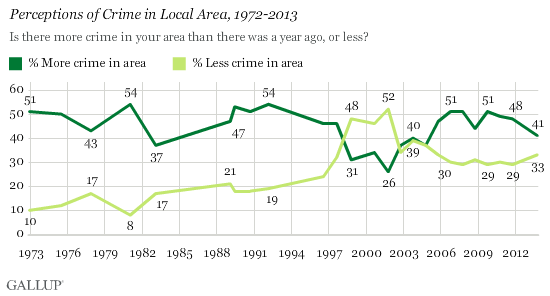

Americans' views about crime in their local area follow a similar trajectory, although Americans tend to be more upbeat about the local situation than the national one. Today, 41% believe crime is up in their area, down from 48% in 2011 and the recent peak of 51% in 2009. However, this is still far less rosy than from 1998 to 2001, when the plurality thought there was less crime locally.

Bottom Line

The U.S. experienced a major drop in crime rates during the 1990s -- for both violent and property crimes -- which has been attributed variously to more sophisticated policing, higher incarceration rates, the Brady Bill, the war on drugs, shifting demographics, and economic factors. Americans clearly took notice of this, as their pessimism about crime began to yield. Perhaps it was the novelty of the situation, or perhaps it had more to do with the leadership at the time, including President Bill Clinton and New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, publicly celebrating their successes in combating crime.

Attitudes changed abruptly in the 2000s, as widespread pessimism returned even as the crime rate continued to edge lower. The focus on terrorism after 9/11 may have been a factor, but so was partisanship. With a Republican in office, Democrats and, to a lesser degree, independents, became more likely to perceive that crime was increasing. In 2010, after President Barack Obama, a Democrat, had taken office, Democrats' and independents' concern waned, but only slightly, while Republicans' increased, helping to keep concern high.

Now, with crime ticking up, Americans are slightly less likely to believe crime is getting worse than they were two years ago. This could change next year if the 2013 data reveal another increase in crime. But for now, this worrisome trend doesn't seem to have caught Americans' attention.

Survey Methods

Results for this Gallup poll are based on telephone interviews conducted Oct. 3-6, 2013, with a random sample of 1,039 adults, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

For results based on the total sample of national adults, one can say with 95% confidence that the margin of sampling error is ±4 percentage points.

Interviews are conducted with respondents on landline telephones and cellular phones, with interviews conducted in Spanish for respondents who are primarily Spanish-speaking. Each sample of national adults includes a minimum quota of 50% cellphone respondents and 50% landline respondents, with additional minimum quotas by region. Landline and cell telephone numbers are selected using random-digit-dial methods. Landline respondents are chosen at random within each household on the basis of which member had the most recent birthday.

Samples are weighted to correct for unequal selection probability, nonresponse, and double coverage of landline and cell users in the two sampling frames. They are also weighted to match the national demographics of gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, region, population density, and phone status (cellphone only/landline only/both, and cellphone mostly). Demographic weighting targets are based on the March 2012 Current Population Survey figures for the aged 18 and older U.S. population. Phone status targets are based on the July-December 2011 National Health Interview Survey. Population density targets are based on the 2010 census. All reported margins of sampling error include the computed design effects for weighting.

In addition to sampling error, question wording and practical difficulties in conducting surveys can introduce error or bias into the findings of public opinion polls.

View methodology, full question results, and trend data.

For more details on Gallup's polling methodology, visit www.gallup.com.