Story Highlights

- Whites more positive than blacks on solution to race problems

- Most blacks say they have not experienced problems with police

- Most whites say civil rights have improved at least "somewhat"

PRINCETON, N.J. -- The outcry after grand juries in Ferguson, Missouri, and Staten Island, New York, decided not to indict police officers in the deaths of unarmed black men has refocused Americans' attention on the continuing, contentious issue of race relations in the U.S. Gallup has measured black and white Americans' attitudes about race for more than 50 years, and both groups continue to look at race relations in significantly different ways, even today.

Gallup data help show how black Americans' and white Americans' views continue to differ in four crucial areas: views of race relations in general, views of discrimination against blacks, views on the need for new civil rights laws and more government intervention and finally, views of the police and justice system.

1. Attitudes About Race Relations in General

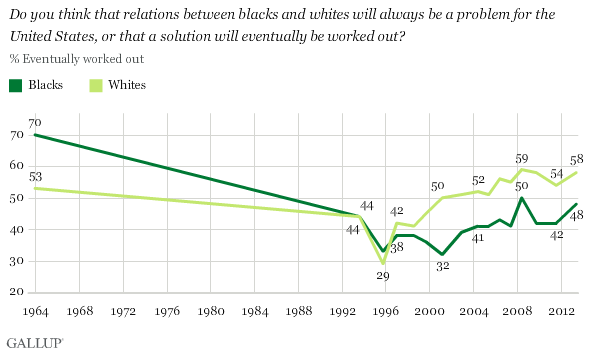

Since the late 1990s, blacks' optimism that there will be a solution to the country's racial problems has consistently trailed whites' by about 12 percentage points. Most recently, in June 2013, Gallup found 58% of whites versus 48% of blacks believing a solution to black-white relations would eventually be worked out. By contrast, in December 1963 -- at the end of what some describe as "the defining year of the civil rights movement" -- a U.S. poll conducted by NORC found 70% of blacks in the U.S. believing a solution would eventually be worked out, while barely half of whites -- 53% -- agreed. When Gallup repeated this question in the early 1990s, blacks' outlook had dimmed to match whites', with 44% of both groups feeling optimistic. Now, the gap has expanded, primarily because whites have become more positive.

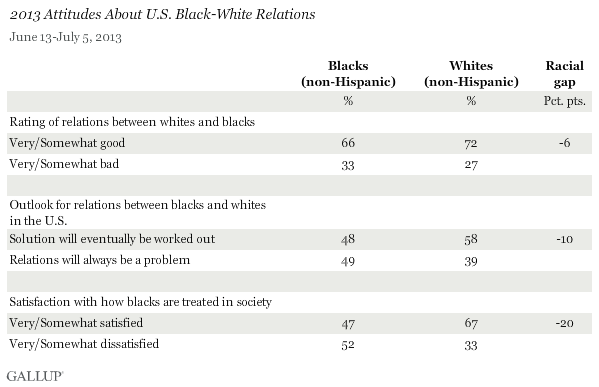

Perhaps one reason for this racial gap in optimism is the even greater gulf between how blacks and whites perceive society's treatment of blacks. In the same 2013 poll, 67% of whites versus 47% of blacks said they were either very or somewhat satisfied with how blacks are treated in society. And blacks' satisfaction dipped further, to 41%, in a special Gallup poll of blacks two months later -- after the acquittal of a neighborhood security watchman in Florida, George Zimmerman, in the shooting death of a 17-year-old black teenager, Trayvon Martin.

Despite blacks' general pessimism about the outlook for racial harmony, and their dissatisfaction with how blacks are treated, the majority are broadly positive about white-black relations. Two-thirds of blacks in June 2013 described white-black relations as very good (8%) or somewhat good (58%), while one-third called them very bad (24%) or somewhat bad (9%). These views were largely unchanged after the Zimmerman verdict, with 62% rating relations as good.

Meanwhile, whites were slightly more positive than blacks in June 2013 about race relations, with 72% calling them good, and 27% calling them bad. This is consistent with whites' slightly more positive perceptions of race relations over the past decade.

2. Views of Discrimination Against Blacks in U.S. Society

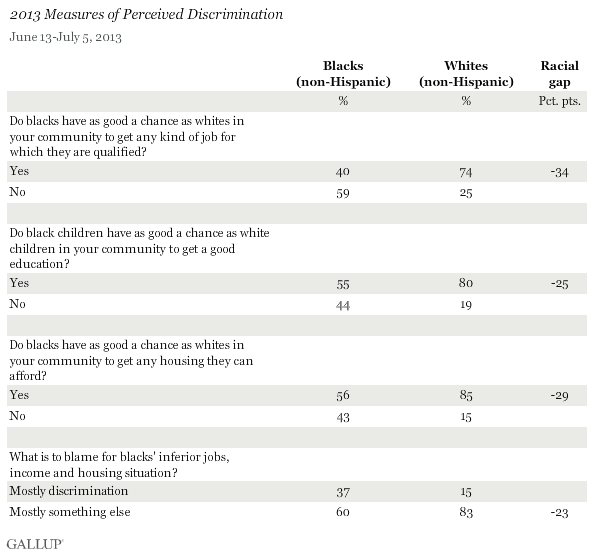

Blacks and whites in the U.S. reject the idea that discrimination is the major reason blacks tend to have worse housing, employment and income situations on average than do whites. But even while this view is in the minority, blacks (37%) are more inclined than whites (15%) to see discrimination as the main factor. Whites and blacks are slightly less likely now than in 1993 to see racial discrimination as the major reason for blacks' objectively worse outcomes in these areas.

Most whites believe that blacks living in the U.S. have the same opportunities as whites for jobs (74%), education (80%) and housing (85%). Blacks, on the other hand, are far more divided, with only slim majorities saying blacks have equal opportunities in housing (56%) and education (55%). Many fewer blacks, 40%, say people of their race have equal job opportunities. The racial gap is largest -- 34 percentage points -- on this question.

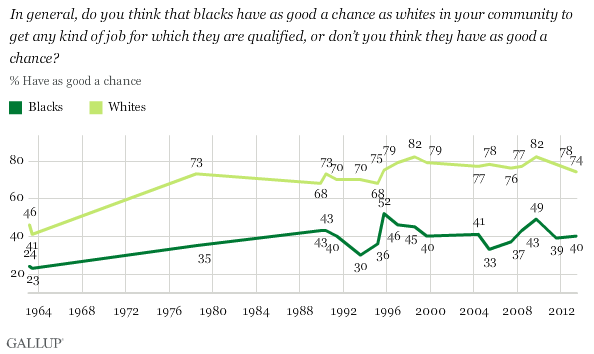

The major long-term change in these attitudes is that blacks and whites now view job opportunities as better for blacks than they did in the 1960s. Whites' positive views have risen more than blacks' views, however, and the gap in these perceptions is actually about as large now as it has been at almost any point. And, although these attitudes among both racial groups are more positive compared with the early 1960s -- before the passage of major civil rights legislation -- they have not changed appreciably since the 1970s.

3. Civil Rights and the Need for Government Intervention and New Civil Rights Laws

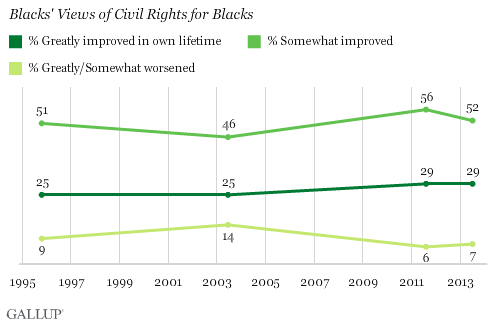

While white and black Americans agree that civil rights for blacks have improved in the U.S. over their lifetimes, whites are much more likely to say that they have "greatly improved." Barely a third of whites in October 1995 -- two weeks after that year's O.J. Simpson verdict -- thought civil rights had greatly improved, but that swelled to 48% by 2003 and reached the majority level in 2011, where it remains.

Blacks, on the other hand, are much more likely to say civil rights for blacks have improved "somewhat," with 52% holding that view in the most recent Gallup update. The percentage of blacks perceiving that civil rights have "greatly improved" is 29%, essentially unchanged from earlier Gallup estimates as far back as 1995, including two measurements since President Barack Obama became the country's first black president.

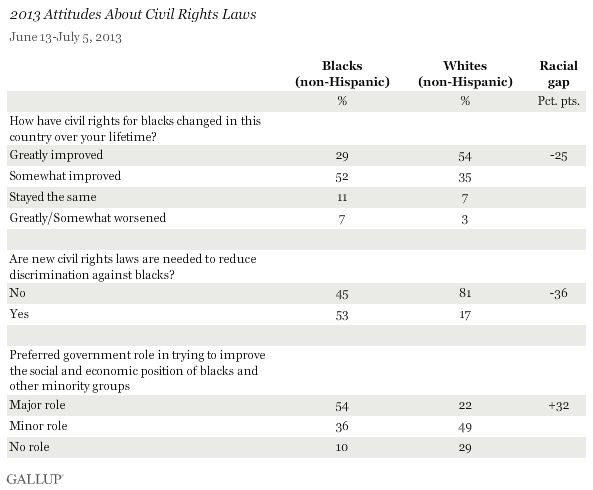

Reflecting their differences on the current civil rights situation for blacks, the two racial groups differ sharply on the issue of whether new civil rights laws are needed to reduce discrimination against blacks. Blacks are essentially split, with a little more than half saying new laws are needed. Whites, on the other hand, overwhelmingly say they are not.

In similar fashion, whites and blacks differ significantly on the need for government intervention to deal with the situation of blacks in America. White Americans generally favor a minor government role in attempting to "improve the social and economic position of blacks and other minorities in this country," while most blacks prefer more significant government involvement. Fifty-four percent of blacks say government's role should be a major one, while only 22% of whites agree. About three in 10 whites say that the government should play no role at all in this.

Substantial racial differences have always been apparent in this question. But whites are now less likely to favor a major government role in assisting minorities than they were during the previous decade. Blacks, though still supportive of a major government role, are also a bit less likely now than they were in 2004-2005 to think that.

4. Blacks and Whites Diverge Widely on Opinions About Police and Justice System

The high-profile incidents in Ferguson and New York City have thrust the issue of race relations and the police into the national spotlight in a powerful way in 2014. Many Americans have noted how differently the races view the police, especially when considering the question of whether black Americans receive fair treatment from law enforcement.

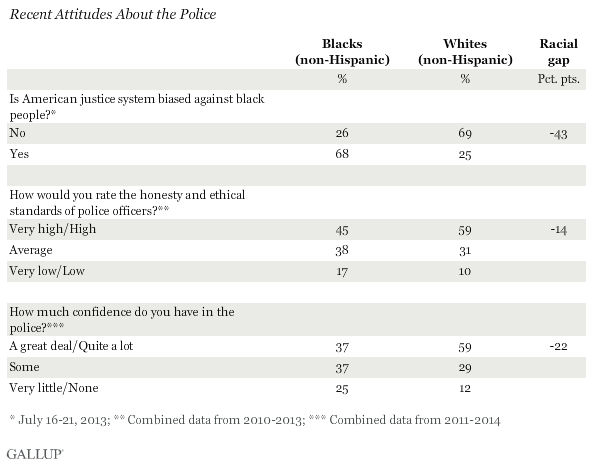

The disparity is greatest when Americans are asked, as Gallup did last year, if the American justice system is biased against black people. Sixty-eight percent of black Americans said the system is biased and 26% said it was not. Whites' attitudes were almost exactly the opposite -- 25% said the system is biased and 69% not biased.

Yet black Americans were more positive toward law enforcement when evaluating the honesty and ethical standards of police officers. Less than half of black Americans, 45%, said officers' standards are high or very high, while 59% of white Americans said the same. Only 17% of blacks said police officers' standards were low or very low, suggesting that at least last year, before Ferguson, blacks held the police in reasonably high regard.

Along the same lines, as of this June, 74% of black Americans said they had at least "some" confidence in the police, while 88% of white Americans said the same. Black Americans' confidence in the police is softer, however, when examining those who said they have a "great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence -- the percentage drops to 37% of blacks (compared with 59% of whites). Recent analysis also shows that blacks living in urban areas have less confidence in the police than those living elsewhere, underscoring the negative context in which encounters between blacks and police are carried out in the nation's metropolitan areas.

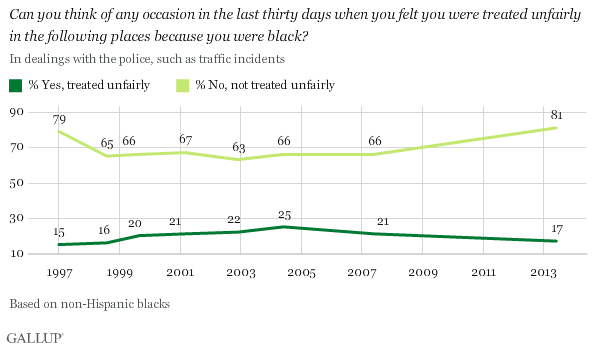

Yet despite the high-profile nature of incidents involving blacks and the police in recent decades, when Gallup asked blacks directly if they had felt they were treated unfairly by the police in the last 30 days because they were black, 81% said no. The 17% who said they had been treated unfairly was down from responses gathered between 1999 and 2007 -- including 2004, when 25% of blacks said they had been treated unfairly within the previous month. There are differences in these views by age and gender, and an analysis in 2013 showed that young black men were more likely than other blacks to report having been treated unfairly by police within the previous 30 days. It remains to be seen, given the current intense media attention toward police treatment of blacks, whether these percentages will rise.

Gallup has additional findings and trends addressing U.S. race relations, as well as links to past Gallup analysis of the data.