The following is adapted from Gallup's new book, Blind Spot: The Global Rise of Unhappiness and How Leaders Missed It.

Mr. President,

You recently took issue with the World Happiness Report and Gallup’s global project to understand how people’s lives are going. Here is what you said during a speech at Columbia University:

[There] is an annual survey known as the World Happiness Report. The goal is laudable. Gross Domestic Product is not the only measure of development. And yet Rwanda always ranks near the bottom, alongside countries mired in conflict.

How could the citizens of the most improved country in the history of the United Nations Human Development Report also be amongst the world’s most miserable? There is a contradiction here.

We looked into it. It turns out that the World Happiness Report is based on a single question from the Gallup World Poll. The way that question is phrased leads Rwandans to answer very pessimistically, for cultural reasons.

In the same survey, Rwandans report high rates of positive and happy experiences every day. Ironically, the question on happiness is not used in the World Happiness Report. The organisers agree the ranking makes no sense. And yet, year after year, the same absurd conclusion is published.

As Gallup’s CEO, I feel compelled to respond.

Let me begin by saying you are right. Rwanda’s ranking in the World Happiness Report (WHR) is shocking -- so shocking that I too have wondered if the data are wrong.

People in the survey research community often say, “I can tell you with 95% confidence that these data are accurate within a margin of error of plus or minus three percentage points” -- meaning there is a 5% chance that the data are wrong. Rwanda’s ranking toward the bottom of the WHR actually made me wonder if that might be the case here.

But what if the data are not wrong?

Gallup has conducted this study in Rwanda since 2006. Every time, the results are the same. Rwandans rate their lives very poorly every time we interview them, and the country always ends up near the bottom of our international rankings.

Here is the trend since we began conducting this survey in Rwanda:

Rwandans rated their lives the highest in 2008 (an average of 4.4). That year, Rwanda tied for 94th out of 115 countries, which was Rwanda’s highest global ranking ever. In 2019, Rwandans rated their lives an average of 3.3, which ranked Rwanda 142nd out of 145 countries.

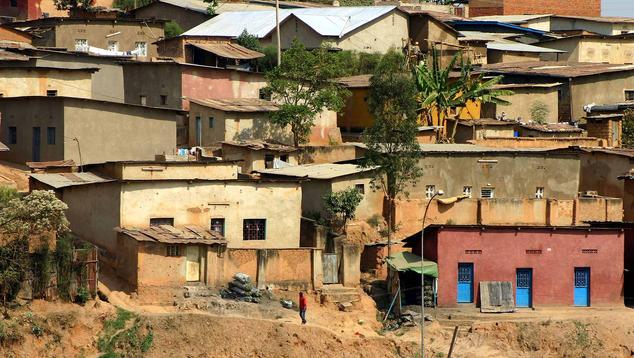

Rwanda does not belong near the bottom of these rankings precisely because the country has been exceptional with respect to development. Every objective indicator shows just how successful Rwanda has been over the past two and a half decades. Indicators like GDP growth, child mortality, school enrollment, and life expectancy all show that Rwanda has not just made improvements, but excelled. The country’s success is so well-known globally that some refer to Rwanda as “the Singapore of Africa.”

So if Rwanda has excelled on virtually every objective measure, then why do people continue to rate their lives so bad?

Whatever the disconnect is, it is a problem. Either there is a methodological challenge, or people’s lives are not going as well as we think they are. Maybe this is a case study for why chasing GDP growth too quickly hurts livelihoods. Or maybe it is something entirely different. Here are three hypotheses for why Rwandans rank their lives so low.

The first is that people are afraid to speak their minds, and they rate their lives worse because of it.

Gallup asks Rwandans -- and people everywhere -- whether they are confident in their national government, local police, military, and judicial system and courts. And the responses we get to these questions in Rwanda are astonishing. Almost everyone expresses confidence in those institutions.

You and your government receive some of the highest approval ratings in the world -- and it has been this way throughout the entire history of our tracking. Look at how Rwanda’s institutions performed compared with the global averages:

Rwanda is No. 1 in every category. There appears to be universal agreement that each aspect of the government is functioning well. And this is what Rwandans report every single year.

We even asked specifically about you, Mr. President: “Do you approve or disapprove of the job performance of President Paul Kagame?” The last time we did the survey, all 1,000 of the people we interviewed said they approved of your job performance. Again, this is highly unusual. This is also the highest approval rating for any leader we have ever recorded.

You are familiar with these trends. When Fareed Zakaria interviewed you on CNN in 2012, you used these figures to defend yourself from his inquiry about whether Rwanda’s tremendous progress was “done with the absence of democracy.”

ZAKARIA: There is the perception that while you have been able to institute a very good sense of rule of law in Rwanda, economic growth, it has all been done with the absence of democracy. The way “The Economist”, which praises Rwanda in its article puts it, the elections are a sham. Many people feel that your party has extraordinary and unfair advantages over other parties.

KAGAME: Well, it is said like that from the outside. When you come to the country, the situation is entirely different. And in fact even partly from outside, if you look at, say, the Gallup polls that have recently been carried out in Rwanda on everything, they show the confidence that people have in the institutions, people have in the government. They all score above 85 percent. Better than you can witness in any African country or even other countries outside. This is ...

ZAKARIA: But you understand the suspicion people have. You win the elections with 95 percent of the vote. I mean -- that’s the kind of margin that Mubarak used to win with in Egypt.

KAGAME: Right.

ZAKARIA: And so at least people think either you are wildly popular ...

KAGAME: Yes.

ZAKARIA: … or there’s something going on.

KAGAME: You see, but that’s where the problem is. Those judging from outside would never accept that there is an issue of popularity in Rwanda or in Africa. Whenever that issue comes up, of popularity, they call it a dictatorship. They think popularity is a preserve of developed countries. But in other situations, leaders can be popular and unpopular.

ZAKARIA: And popular is one thing, but winning 95 percent of the vote is another.

KAGAME: Absolutely. But you see, you have to put all matters in context. If you take it out of context, then you lose the point. One, I have told you about outsiders coming to the country and assessing the feelings of the citizens of our country. Which they have interacted with independently and at all levels, the score is very high. This is a practical thing, this is a fact. Now, the other is in that context, you have to know where Rwanda is coming from. Rwanda the other day, 18 years ago, starting from scratch. In fact, supposed to be a failed state. And it has come out of that. People rallied around the leadership that was there and building on their own effort and a desire to be out of this situation, this is what produces the kind of things you see.

(Transcript from CNN website)

Your defense is persuasive. We should not impose the West’s views or beliefs on Rwanda, but we can ask this question: Are Rwandans telling us the truth?

Maybe they don’t feel like they can freely express themselves. And freedom is important. According to the 2019 WHR, a sense of freedom matters significantly in the making of a great life.

One way to evaluate the freedom of a country is through the Human Freedom Index produced by the Cato Institute. In 2020, it found that Rwanda ranked 78th out of 162 countries with respect to freedom. Rwanda received this middle-of-the-pack ranking because while the country excels in economic freedom (ranking 59th), it performs poorly on personal freedom (ranking 102nd).

The latter evaluates personal freedoms such as religion, movement, and assembly. Seven subindexes are compiled to determine a country’s final score for personal freedom. Of the subindexes, Rwanda ranks the worst on the Association, Assembly, and Civil Society subindex, which covers these political freedoms: civil society entry and exit, assembly, freedom to form political parties, autonomy of opposition parties, and civil society repression. Rwanda also receives a score of zero for media freedom in a separate subindex.

The impact of freedom of expression is hard to quantify, but it could be affecting how Rwandans rate their lives.

The second hypothesis for why Rwandans rank their lives so low is that there may be a measurement issue. Our survey questionnaire could be creating confusion with one of the government’s most popular benefits schemes.

The Ubudehe classification system is the Rwandan government’s program to determine which people qualify for education and healthcare benefits. The level of benefits a person receives is determined by where they rate in this classification.

The classifications are straightforward: Every person is categorized using a number system from one to four. A one means that you are part of the lowest income group in Rwanda, and you receive the maximum benefits from the government. If you receive a four, it means that you are among the wealthiest people in Rwanda, and you receive the least benefits. Getting in a lower category gets you more benefits from the government.

Now imagine someone comes to your house, knocks on your door, and says, “Rate your life on a scale of zero to 10.” If you thought you were being asked a question that might affect how you are categorized in the Ubudehe classification system, you might want to score it as low as possible to increase your chances of receiving more benefits from the government. If this confusion were happening -- it could unintentionally lower scores for the entire country.

However, when we begin each of our interviews, we are clear about the purpose of the survey. This theory would mean that people are getting confused despite interviewers explicitly telling them what the survey is about. Plus, the Ubudehe classification is a 4-point scale, and our life evaluation question is an 11-point scale (zero to 10). This hypothesis is a stretch, but it is possible.

Of course, in December 2021, the government changed the Ubudehe classification categories from numbers to letters (A-E). While we have not conducted a survey in Rwanda since 2019, future surveys may help us understand if people were confusing Gallup’s zero to 10 life evaluation scale with the numerical Ubudehe classification system.

The third possible reason why the happiness scores in Rwanda rank low may have to do with how the perpetrators of the 1994 genocide and their families rate their lives -- an idea I first heard from a bishop in Rwanda.

I will never forget meeting this bishop. During one of my visits to Rwanda, I drove about two hours outside of Kigali to speak with this well-known and very influential religious figure. He operates out of a small community center, which is where I met with him.

The bishop got down to business before I even sat down. He had his iPad with him, and on the screen was the World Happiness Report. He held up his device, showed me the image of the WHR, looked at me, and said, “You know this is rubbish, right?”

I knew beforehand that he hated the results of the WHR -- like so many leaders in Rwanda -- so I was not surprised when he said it. “Well, let’s start there,” I said. “Why do you think that?”

He told me what I had heard from so many other Rwandan leaders before: Rwanda was a shining city on a hill for Africa, and any objective measure will tell you that.

I was not there to persuade him that the data were right; I was there to listen. But most of the meeting failed to produce any new insights. He talked about why Rwanda was having so much success and said that Gallup’s data were wrong. He kept talking, and it was starting to get dark out.

So I took a different approach. “What if we assume for the moment that the results of the survey are right? Let’s assume that Rwandans actually rate their lives as low as that report says. If it were true -- why would they rate their lives like that?” I asked him.

I could tell that the question surprised him. He sat back and really thought about it. Honestly, I was surprised he even entertained the question.

After sitting in silence, he paused, looked at me, and offered one of the most profound insights in wellbeing research I have ever heard.

“As you know, our country went through a devastating genocide in 1994. One out of every 10 people in my country died. Everyone lost someone. But I do not think it is the victims of the genocide that are rating their lives badly. I think the people who might be rating their lives lowly are not the victims, but the perpetrators.”

When people from the West see Rwanda’s poor rankings in the World Happiness Report, they tend to think about the one thing they are most familiar with about Rwanda -- the 1994 genocide.

As you know, Rwanda became a colony of Belgium following World War I. And while distinctions based on class existed during prior German rule and perhaps longer, the Belgians made it official. According to the Belgians, the minority of the population -- the Tutsis -- had physical and cultural characteristics that distinguished them from the Hutus, the majority. The Belgians considered the Tutsis to be taller and more affluent than the Hutus and therefore put them in charge of the country. This caused the Hutus to resent the Tutsis.

In 1962, Rwanda became independent. The Hutus took power not long after a military coup under Juvénal Habyarimana in 1973. His presidency lasted 20 years, with Tutsi-Hutu relations descending into civil war in the early 1990s. Then, with international support, the warring parties signed a truce known as the Arusha Accords. And although the conflict ended, it did not ease tensions.

The climate was best described by what was on the airwaves. Hutu radio shows openly referred to Tutsis as cockroaches and called for their extermination. The country was doused with so much emotional kerosene that one match could put Rwanda in flames.

That match was lit on April 6, 1994. That day, President Habyarimana’s plane was shot down, killing him and everyone else on board. That moment kicked off one of the bloodiest periods in world history -- a genocide that took the lives of roughly 800,000 Rwandans.

The Hutus claimed that the Tutsis were behind the death of the president. Using widespread communication like radio, Hutu leaders encouraged all Hutus to take up arms -- mainly machetes -- and kill every Tutsi in their neighborhoods. Next-door neighbors were slaughtering each other.

Almost 1 million people died in a matter of weeks. The world stood by while it happened. The genocide ended only with the successful military campaign by the Rwandan Patriotic Front, led by you, Mr. President.

What people internationally are less familiar with is what Rwanda did after the genocide to come together.

Following the genocide, justice seemed impossible. Killing almost 1 million people in just weeks meant that a large part of the population had to be involved. In the aftermath, roughly 600,000 people confessed to participating in the genocide.

No matter what country you live in, 600,000 murder cases is a lot. But for a country with roughly 8 million people, 600,000 is almost one-tenth of the entire population. For everyone to receive a fair trial, the judicial process would take decades and resources the government did not have. Rwanda also could not put 10% of its country behind bars. It needed to do something different.

To solve this problem, Rwanda set up special community courts known as gacaca courts. They were established to promote healing between the victims and the perpetrators. If the accused admitted to their crimes and apologized to the victims’ families, they would have reduced prison sentences and be allowed to be reacclimated into society.

But reacclimating meant that the people who committed those atrocities against their neighbors would continue to live alongside them. The bishop’s theory is that the perpetrators continue to carry the pain from their crimes from 1994 every day -- and so do their families.

Researchers from the University of Konstanz and the University of Butare attempted to test this theory. According to them, “… no study has yet investigated the mental health of Rwandan genocide perpetrators.”

The researchers recruited victims and perpetrators of the genocide to participate in the study. They looked to the prisons of Butare and Kigali to find perpetrators who would be willing to take part in such a study.

The study revealed how much pain the victims continue to carry with them. Almost half experienced PTSD and depression, 59% had anxiety, and 19% were suicidal during the time of the study. The results from the interviews with the victims may very well explain a large part of why people overall rate their lives so poorly in Rwanda.

The researchers also examined the findings from interviews with the perpetrators. While the perpetrators did not experience PTSD (14%) and anxiety (36%) at the same rate as the victims, they did experience depression (41%) and were at risk of suicide (19%) at the same rate as the victims. However, the high rates of depression and suicide among the perpetrators may have been caused by the fact that they were in prison.

Another study replicated this research but with genocide perpetrators who had left prison. It found that the perpetrators had similar rates of PTSD, anxiety, and depression as the victims. So imprisonment may not have been the most likely factor for why perpetrators were experiencing these mental health issues.

So, was the bishop right? Understandably, the pain from the genocide has not subsided. Additional research finds that even the children of genocide victims and perpetrators carry this pain.

The enduring emotional effects of the 1994 genocide, not just for the victims but also for the perpetrators and their children, may be what’s causing Rwandans to rate their lives so low.

But the truth is, we cannot say definitively why Rwandans rate their lives so low. Yet despite these ratings, Rwanda remarkably remains an economic and development star. And Rwanda’s success in development is not the only thing that inspires people everywhere.

In 2019, Voice of America ran a story about a woman named Louise Uwamungu. She lost eight family members during the genocide. She even knew the name of the man who killed her cousin -- Cyprien Matabaro. He went to jail for his crime, and Louise knew where he went to prison.

Louise wanted revenge. Her brother was one of the prison guards, and she drew up a plan for how he could kill Cyprien -- but her brother refused to do it.

Cyprien sat in prison for years after the genocide. When he was released, things got worse for Louise because after Cyprien left prison, he moved in next door to her.

Cyprien tried to make things better. He begged Louise for forgiveness. They went through the process of truth and reconciliation, during which he admitted to his crimes and told her what happened. The process helped Louise and the rest of her family members continue their healing.

The tragedy in Rwanda can never be made right, but inspiring stories -- like the story of Louise and Cyprien -- can make things a little better. Because today, they are friends. They even farm and socialize together.

People like Louise and Cyprien made Rwanda the shining city on a hill that the world knows it for today. But why people continue to rate their lives so poorly remains a mystery. It might be a lack of personal freedom, confusion with government services, or the emotional trauma from the genocide. The answer may even be a combination of those factors or something entirely different.

I remain equally as surprised as you at the results of the World Happiness Report. My hope is that we can arrive at a more definitive answer for why Rwanda ranks so low in happiness despite experiencing so much economic and development success. If we do, it will benefit the entire world.

Very respectfully,

Jon Clifton