On May 22, the president and congressional leaders met to discuss infrastructure -- one of the American people's highest priorities for their elected representatives. Within 10 minutes, however, the meeting was called off. Nothing was accomplished.

The exact circumstances of what happened on May 22 aren't as important as what it tells us about the broad failure of our leaders to meaningfully address the nation's priorities. The episode stands as an exemplar of the reasons so many Americans are frustrated with government. The American people watch their government struggle and fail to make progress on issues where there is public consensus, and as a result the people's faith in their government remains well below historical norms.

Broad Public Support for Infrastructure Spending

Developing new government programs to fix the nation's infrastructure is a no-brainer if there ever was one. Infrastructure is one of Americans' highest priorities, and one supported by rank-and-file citizens of all political persuasions. Apparently, it is also supported in theory by elected representatives on both sides of the aisle.

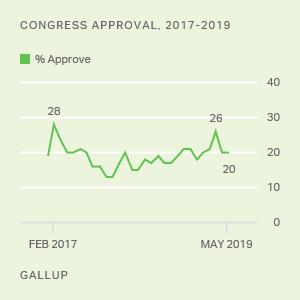

But this problem in need of a solution has lost out to another, bigger problem in need of a solution -- the government itself, once again this month rated as the most important problem facing the nation. Congress this month receives a 20% job approval rating. The people have very low confidence in the government to handle either domestic or international affairs, Congress has less trust than any other institution Gallup tests, and members of Congress have lower honesty and ethics ratings than car salesmen.

As Washington Post reporter Mike DeBonis summarized after last week's infrastructure debacle: "This week's Washington roller-coaster ride trashed hopes that an unconventional president and a divided government might produce breakthroughs on matters of bipartisan concern. Instead, lawmakers appear poised to continue an eight-year trend and spend the next 18 months lurching from deadline to deadline, crisis to crisis …." A construction executive summarized what happened this way: "Politics kind of killed infrastructure once again. The real losers in this are the American people."

Government Dysfunction Not a Newly Discovered Phenomenon

The dysfunctions that plague the way our government operates are not unrecognized phenomena. Scholars, social scientists and journalists have provided legions of analyses and proposed solutions to the problem -- including estimable volumes such as Why Government Fails So Often: And How It Can Do Better (by Peter H. Schuck) and It's Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided With the New Politics of Extremism (by Thomas E. Mann and Norman J. Ornstein). Other articles and opinion pieces have covered a wide spectrum of possible solutions -- such things as changing the rules committee in Congress, paying congressional staff more, reforming the power of leadership and how chairs are chosen, shifting the days in which Congress is in session, expanding the members of Congress, and redistricting.

One newly elected member of Congress recently shared his opinion of what's wrong: "The problem [with Congress] is a defective process and a power structure that, whichever party is in charge, funnels all power to leadership and stifles debate and initiative within the ranks. Your average member of Congress, far from being drunk on power, actually has very little of it outside a cable news studio."

And speaking of cable news, still other critics focus on the impact of the revenue-hungry cable news channels in creating the emotionally charged polarization that facilitates political dysfunction.

But it's one thing for scholars and critics to write about problems and potential solutions -- and for people like me to continually point out how disgusted the people of the United States are with their elected representatives. It's another altogether to figure out how to actually implement change.

The Great Challenge Is How to Bring About Change

We know the Founders shrewdly set up a system where the ultimate power in our representative democracy resides with the people themselves. Voters can elect and send new people to the House, the Senate and the presidency, and ultimately the people can change the Constitution itself. But elections come and elections go -- and, either because of the way the election system operates or the way Washington operates once elected officials get there, the demonstrable fact is that the people of the nation continue to be dissatisfied with the way their government is working.

The American public would certainly go along with any number of proposed changes to the way elections and government work -- changing to a national primary, shortening the election season to five weeks, moving to a direct popular vote, redistricting and creating more compromise. Most Americans are, I think, unfamiliar with the arcana of congressional rules and process, but would be open to changes there as well if persuaded they would improve the way the institution works. But few leaders, and in particular few candidates for office, have been able to mobilize public opinion into effective demands for these types of changes.

We need, it seems to me, leaders and candidates who are focused on the process of government and on exactly how change is going to be brought about, rather than on lists of proposed new substantive policies that have little or no chance of becoming law.

We're not seeing this at the presidential level as we watch the mad rush of candidates vying for their party's nomination in 2020. Candidates put forward many "plans" for new policies, few of which have any probability of implementation. Rather than saying we need [insert policy proposal X, Y or Z], a candidate would optimally say we need a process by which leaders on both sides can be brought together to find the best way to handle policy area X, Y or Z. This would fit well with the public's desire for more compromise in order to find solutions, and less obstinate sticking to preconceived or ideological positions.

Recent history suggests we are not likely to see much of this type of shift from policy to process from our candidates or elected leaders. The normative tradition of focusing on isolated policies, ideological positioning and short-term partisan gains, with little big-picture discussion of the dysfunctions of the broad system, is too strong.

Certainly, we have seen shifts and changes in the body of our elected representatives over the years -- to some extent reflecting efforts on the part of the people to make their voices heard. As one major example, history will show that the current president's election in 2016 was to a degree a reflection of underlying discontent with government, as was the shift in control of the House back to the Democrats last November. But neither of these changes have so far brought about meaningful change in our indicators of the people's disdain for government. Work on the people's priorities is still stalled. More change, clearly, is needed.