Story Highlights

- Singapore's GDP growth has averaged 6.8% annually since 1976

- Political pressure mounts against further population growth

- Only 9% of Singapore's workforce is engaged

As Singapore nears its 50th anniversary, the city-state faces intense global competition for talent.

Singapore comes to this competition -- not to mention to its half-century mark -- in a seemingly strong position. The city-state's GDP growth has averaged 6.8% annually since 1976, and the country's financial reserves -- though they are kept deliberately vague -- don't appear to be in danger of drying up soon. Though the country's population has more than doubled from just over 2 million in 1970 to 5.47 million in 2014, its unemployment is 2%, and the economy is virtually at full employment.

Singapore's national well-being is the highest it has been since the global financial downturn: 43% of respondents in 2014 rated their lives highly enough to be considered "thriving," while only 1% of respondents rated their lives poorly enough to be considered "suffering."

This impressive developmental trajectory is hard for a country to top, but many of Singapore's global competitors are cities. Hong Kong has long been seen as a rival for pole position as a financial hub in Asia, and with "megacities" -- cities with more than 10 million in population -- on the rise, the list of Singapore's potential rivals expands. From 1950 to 1960, 60% of the growth of megacities was in the developing world; between 2000 and 2010, the developing world accounted for 90%. The fastest-growing megacities include two in Singapore's own backyard in Southeast Asia: Bangkok in Thailand, and Jakarta in Indonesia.

Competition Among Megacities Intensifies Battle for Talent

The pace of growth in these megacities has intensified competition for many of the elements that Singapore has relied on to grow -- most worrying being the previously mentioned competition for talent. Singapore has long aimed to be the "home for talent" in Asia. In 1970, 97% of the country's population were residents; in 2014, just over 70% were.

Much of the influx in nonresidents was driven by foreign talent, or expatriates with experience or expertise locals lack. Now, as domestic political pressure mounts against further population growth, while existing infrastructure cannot accommodate the pace of population expansion, other growing megacities seem more attractive as alternatives to Singapore. Because of these factors, recruiting a steady supply of foreign talent may no longer be a sustainable strategy to meet Singapore's talent needs.

In Singapore's growing technology sector, for example, a recent report ranked the city-state last among 20 startup-friendly cities for access to talent, taking 21% longer to hire a software engineer than in Silicon Valley, California. Singapore also ranks as one of the world's most expensive cities, so even with its relatively low personal income tax rates, employment in the country might not be as enticing as it used to be for foreigners. In the short and medium run, Singapore must improve the political feasibility of importing foreign talent, attract and retain the right talent, and enhance the productivity of the talent it has to stay ahead of its competitor megacities.

Reversing a long-term decline in labor productivity will require exploring new solutions. Though productivity grew at an annual rate of 5.2% in the 1980s, this figure fell to 1.8% in the 2000s. The quality of the country's resident labor pool is very high: The literacy rate among residents is a 96.7%, while almost 26% of residents 25 years and older are university graduates.

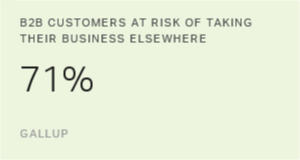

Only 9% of Singapore's Workforce Is Engaged

Ensuring that the labor pool is productive may be a challenge: According to Gallup's 2013 State of the Global Workplace study, only 9% of Singapore's workforce is engaged, while 91% are emotionally disconnected from their workplaces and less likely to be productive. Gallup researchers have conducted eight meta-analysis studies over 15 years, and each time have observed a strong relationship between employee engagement and productivity. In the most recent study, workgroups with high levels of engagement are 21% more productive than workgroups with low levels of engagement.

Gallup studies also suggest that only three in 10 people have the naturally recurring thought patterns to manage individuals for performance excellence, increasing workers' productivity. Choosing the right people to be managers and leaders and investing in the development they need to excel could hold the key to unlocking the national push for higher productivity. Small- and medium-sized enterprises employ about 70% of Singapore's workforce, so finding and deploying a scalable, cost-effective solution for these organizations to select, engage and develop high-performing talent could help the country improve its competitive position in the global war for talent while improving the productivity of the talent it already has.

A growing body of research suggests that optimizing the workplace yields strong productivity gains at a high return on investment. Engaged employees currently make up only 9% of Singapore's workforce, so increasing this percentage could offer at least as high a return on investment as a technological or process improvement. If workplaces in Singapore can harness their people's potential, just imagine what could be in store for the country in the next 50 years.

A version of this article appeared in The Business Times.