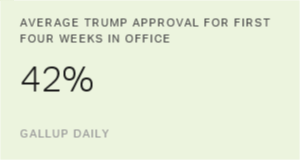

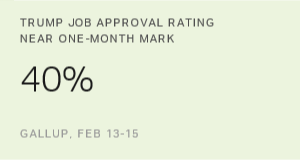

Donald Trump has skipped the traditional honeymoon period usually accorded presidents when they first take office. Americans, including those from the opposing party, typically have given a president a relatively high job approval rating until he settles into the job and makes moves that change their opinions. Not so with Trump. He came out of the chute with very low approval ratings from Democrats and relatively low ratings from independents, resulting in his beginning his term with an average 42% approval rating across his first four weeks in office, including a current 42% rating for the last four days (Feb. 17-20). These numbers are lower by far than for any other president over his first month in office.

The pattern of Trump's approval -- the internals by party -- are, however, not at all unusual for a president with an overall 42% rating. The antipathy Democrats have toward Trump is no different from the antipathy Democrats had toward George W. Bush when he had an overall 42% rating, and no different from the antipathy Republicans had toward Barack Obama when he had an overall 42% rating. And Trump's support among his own partisans is slightly higher than partisan approval for Bush and Obama when they were at 42%.

Trump's most recent four-day average (Feb. 17-20) breaks down to 86% approval, 13% disapproval among Republicans and 8% approval, 89% disapproval among Democrats.

When George W. Bush had an overall 42% approval in October 2005, he received 83% approval from Republicans, about the same as Trump has now, and 8% approval, 89% disapproval among Democrats, exactly the same as Trump has now. In other words, Trump's pattern of polarization is identical to the previous Republican president's when he had the same overall ratings.

Barack Obama had a 42% approval rating the week of Oct. 20-26, 2014, and his ratings among the opposing party, Republicans, were 6% approval with 91% disapproval, virtually the same as Trump's and Bush's among the opposing party when they were at 42%. Obama received slightly lower approval from his own partisans (78% among Democrats) than Trump or Bush among their partisans (86% and 83%, respectively).

So while the speed with which Trump's overall rating has dropped to the low 40% range is unusual, the highly polarized way Americans are looking at Trump is not at all unusual for recent presidents. The default at this point in history is for a very significant proportion of the opposing party to disapprove of whatever a president is doing. Bush and Obama faced the same situation in their presidencies. I have no doubt, based on her low favorable ratings while a candidate, that Hillary Clinton would have as well.

So how then does a president operate in a situation in which a sizable proportion of his constituency disapproves (and strongly disapproves, based on some new data we are looking at) of what the president is doing?

A writer at the Vox website called attention to Trump's comments at a recent press conference: "We've begun preparing to repeal and replace Obamacare. Obamacare is a disaster, folks. It's a disaster. You can say, 'Oh, Obamacare!' -- They fill up our rallies with people that, you wonder how they get there, but they're not the Republican people that the representatives are representing."

The point here was Trump's seeming assertion that Republican members of Congress were in office to represent only Republicans back home in their districts, not all of the people. By extension, was Trump implying that he represents only Republicans and those who voted for him, not all Americans? The author argues this is the case, quoting Trump from his previous business life emphasizing that life is a negotiating contest in which one attempts to best and win out over the competition.

If Trump has brought this approach to life into the presidency, then his philosophical views on governing in a divided, polarized America are clear. His object is to reflect his supporters, out-negotiate and outfox the "enemy" (in this case, Democrats and those who disapprove of his performance in office) and crush them into submission. There is certainly evidence of that approach in his view of much of the media, which he assumes mainly represents the views of his opponents and is therefore the "enemy of the American People." In this situation, Trump's "people" is not all of the people (which would include Democrats who are his opponents) but Republicans and his supporters.

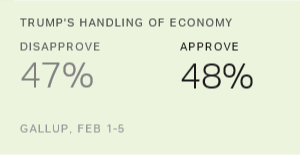

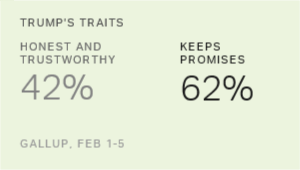

The American people as a whole continue to want their leaders in Washington to compromise to get things done rather than sticking to their beliefs. Trump may view his situation a little differently, thinking that he can get things done and stick to his core beliefs without compromising, but the validity of those assumptions remains to be seen. Certainly it is fair to say that Trump views business as usual in Washington, presumably involving compromise, as something he is trying to avoid. His emphasis is on keeping his promises to his supporters at all costs, not on trying to understand why others might not agree with those promises.

In that regard, it's important to recognize that not all approaches to negotiation involve assumptions that one's opponents should simply be overpowered. The highly influential book on negotiation Getting to Yes argues that one should in fact attempt to take into account the interests of one's opponents and thus more effectively reach an agreement that comes close to satisfying both sides.

I also like to quote Stephen Covey, one of whose "seven habits of highly effective people" is to "seek first to understand, then to be understood." This doesn't imply that a leader has to agree with those who disapprove of him or dramatically change his core beliefs. But as Covey would argue, attempting to understand why the majority of the country's population disapproves of what one is doing almost certainly would allow a president to be more effective than ignoring or denigrating those beliefs.

The issue of how to govern in a polarized world is not new and was integral to the thinking of the Founding Fathers as they attempted to set up a system that would take into account rancorous and deeply held differences in viewpoints among factions of the population.

This remains as daunting now as 225 years ago. The highly polarized environment for today's modern presidents is not going to go away. Neither is the challenge of attempting to figure out how best to deal with it. The American public is clearly dissatisfied with how government in Washington is working. Trump was elected in part because of his promised role as a disrupter, pushing to get things done while not being politically correct, so some change in procedure is appropriate. But settling in on exactly what those changes are and how best to execute them remain Trump's biggest challenges.

Explore President Trump's approval ratings in depth and compare them with those of past presidents in the Gallup Presidential Job Approval Center.