President Donald Trump's decision to pull the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement on climate change and the strongly negative reaction by some groups regarding that decision are focused mainly on trade-offs and questions about the data used in evaluating those trade-offs.

The Paris Agreement essentially says that to control carbon emissions and to limit the rise of the world's temperature, it is necessary to take actions that could affect jobs, technology and finances, among other considerations.

Trump's June 1 speech outlined his conclusions about the trade-offs and data for evaluating them. He claims the agreement would have disastrous effects, not only on U.S. jobs, but also on the nation's financial situation -- given the requirement to spend billions on reducing pollution and helping other countries to do so. Plus, also on the negative side of the ledger, Trump said the agreement would disadvantage the U.S. compared to other nations.

In terms of the agreement's benefits to the world's climate, Trump claimed they would be minimal. He said, "Even if the Paris Agreement were implemented in full, with total compliance from all nations, it is estimated it would only produce a two-tenths of one degree … Celsius reduction in global temperature by the year 2100," and went on to call that a "tiny, tiny amount."

Others, of course, have totally different takes on the facts of the matter, saying that the gains to the planet's climate would be substantial and that the economic costs would be minimal, particularly when taking into account new jobs in the renewable energy sector.

Thus, Trump argued that the trade-offs come down against the agreement, while Trump critics argue that the trade-offs come down in favor of the accord.

Which brings us to the American people -- my focus. As seen from Trump's announcement and the reaction to it, there is certainly no universal consensus on the facts involved. And the average American is certainly not in a position to be able to carefully evaluate claims about the future impact of the accord on jobs, the budget, the climate and so forth.

What we do know is that Americans' general attitudes are broadly sympathetic to both sides of the trade-off equation -- the importance of jobs and the economy and the importance of the environment.

Americans value jobs, want an expanding and exuberant U.S. economy, and certainly where possible would like to restrict unnecessary federal government expenditures. It's hard to argue with these basic core values that Trump emphasized in his speech. (A caveat here is that these economic concerns are somewhat diminished since Americans tend to see the economy as getting better.)

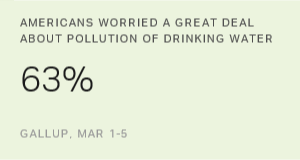

Americans are also becoming more concerned about the environment and climate change, although neither of these is a dominating issue on their radar. Americans say they worry about the quality of the environment as much as any other topic tested in a recent poll, except for healthcare. (The caveat here is that neither the environment nor climate change shows up significantly on our measure of the most important problem facing the nation today.)

Still, all of these results suggest that Americans are, in essence, open to argument about the relative benefits of the Paris Agreement. That is, Americans are open to argument about the accord's positive impact of helping the environment and reducing the upward trend in the earth's temperature on the one hand, and its costs in terms of slowing job growth and increasing federal expenditures, as well as its fairness to the U.S., on the other.

This brings us back to politics. In situations like these, Americans are looking to leaders and authorities for guidance. And in an America that is increasingly polarized, they tend to look for cues from political leaders who are relevant to them based on those leaders' political orientations.

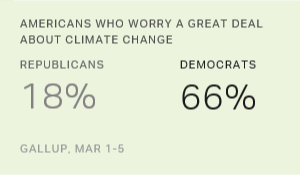

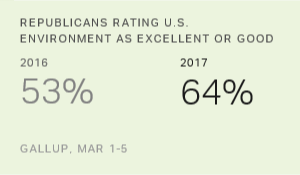

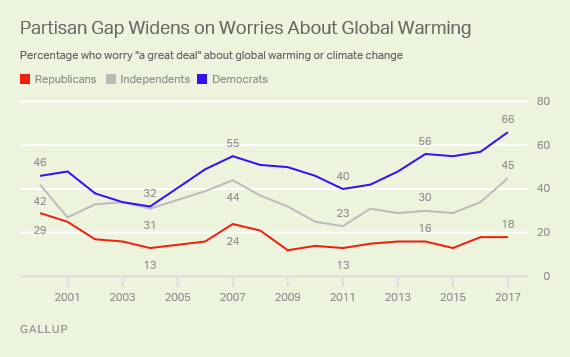

On almost every environment and climate change and global warming issue we have tested, there are major partisan gaps.

Here's an example:

Republicans -- Trump's base -- are much less worried about the environment than are Democrats or independents, and that gap has increased as the last two groups have become increasingly concerned about the issue. This means that the trade-off scales almost certainly tilt toward the jobs/money side of the ledger for Republicans and toward the climate change side for Democrats.

Trump's actions regarding the accord -- keeping his campaign promise -- clearly play well to a base whose lower level of concern about climate change makes his actions seem reasonable. And of course, the partisan gap on this issue makes it clear that Democrats will tilt against his decision on substantive grounds, in addition to the underlying partisanship, which makes them more negative on almost anything a Republican president might do.

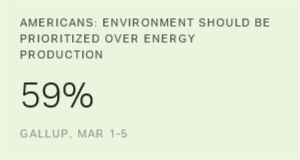

We have not tested Americans' specific reaction to the decision to drop out of the accord. We have trended questions that ask the public to prioritize their concern about the environment against their concern about production of traditional energy sources such as oil, gas and coal and against their concern about economic growth. In March, a time when the economy was perceived positively and when there was much less concern about the cost and availability of energy than in times past, Americans tilted toward prioritizing protection of the environment over both of these concerns.

These findings suggest that the public as a whole might initially tilt against Trump's decision. A poll conducted by others in 2015 and 2016 prior to the June 1 announcement showed majority support for staying in the pact. That wording did not include a reference to Trump. A question that does ask explicitly about Trump's June 1 decision, I have no doubt, will produce highly partisan results.