There's a coming data revolution in higher education, but it's not the "big data" revolution that many have been hyping. This revolution will be more about the right data than bigger data. And it's not data on traditional education metrics, but rather data that have been largely -- indeed, embarrassingly -- missing from higher education.

This revolution will be about the voices of consumers and constituents in higher education. It will be defined by the addition of behavioral economic measures, not just classic economic measures. And it will usher in a new era of rigorously tracking the expectations, experiences, emotions, and outcomes of students, alumni, staff and faculty in the spirit of understanding how institutions of higher education are performing, and how they can improve. Boards, take heed.

As with any industry or sector -- from business to government -- understanding the human side of the ledger is critical to organizational performance. The same is true for higher education. It's almost impossible to imagine the world today without the voice of the consumer. We decide on restaurant selections by using tools like Yelp to see ratings from customers. Every time we take an Uber, we provide ratings on the drivers. Nearly every experience we have today measures our interaction with a product and our feelings about it. Imagine if we actually had this kind of information to inform how we measure and improve quality across higher education.

With rare exceptions -- such as business school rankings, where alumni surveys are a component of the criteria -- higher education is not systematically measuring the experience of students or alumni. Current college rankings are not reported in the vein of Consumer Reports, which includes reviews from consumers who own and have tested products and services; the current college rankings include no such thing.

College rankings certainly drive plenty of consumer attention to higher education, as parents and prospective students flock to websites and magazines in order to judge which colleges and universities are "best." In reality, we have no idea which are best. If we judge "best" by factors like admissions selectivity and endowment size, we know which institutions score well. But if we were to attempt to judge colleges and universities by the learning growth and development of students from matriculation to graduation, we'd have no idea. No one has ever measured this. Or what if we were to judge institutions by the career and life outcomes of alumni? Remarkably, that hasn't been done, either.

The uncomfortable truth is that higher education desperately needs to end its obsession with rankings and focus more on simply improving -- in all the right ways. The coming data revolution will shift colleges' and universities' focus from how they fare in rankings to a serious look at whether their own institution is improving year-over-year on the metrics that matter most to their own constituents and consumers.

Not only are we missing the important voices and emotions of people involved in the process of learning, but classic economic measures in education have come increasingly under fire. The United States achieved its highest high school graduation rate in history this past year, yet the public dialogue about schools in our country is as negative as it's ever been. The average college GPA has gone up a full letter grade in the past 30 years, thanks to rampant grade inflation across the industry. It's hard for employers to understand what a good grade is anymore because everyone has a good grade. Google, for instance, no longer even asks candidates for their grades and test scores because they have found no correlation between those measures and success on the job.

This is not to suggest that we abandon metrics like grades, tests and graduation rates; they can and will serve an important purpose. But we have an immediate imperative to expand our scope beyond these limited metrics.

In 2014, Gallup and Purdue University partnered to conduct a large-scale, nationally representative study of college graduates and their long-term outcomes. The Gallup-Purdue Index was the first effort of its kind in the several-hundred-year history of higher education.

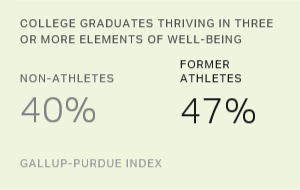

This research revealed that what matters is the kind of emotional support and deep, experiential learning the graduates experienced as students. And the whole story is told by behavioral economic measures. Graduates who were emotionally supported during college or who had deep, experiential learning are two times as likely to be engaged in their work and thriving in their well-being later in life.

Applying those six key experiences to a specific segment of higher education, the Gallup-USA Funds Minority Graduate study looked at historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and unearthed findings that shifted how we think about outcomes from these institutions. On measures like graduation rates and student loan default rates, HBCUs don't fare well. But in looking at the percentage of their graduates who strongly agree they had the six key experiences, the story changes dramatically. Black graduates from HBCU institutions are two to three times more likely to hit the mark on these experiences than black graduates from all other types of institutions. It's a remarkable difference. The behavioral economic measures that look so good for HBCUs don't change the classic measures like graduation rates that don't look so good, but this most definitely changes our view of their overall performance.

Board members need to know where their institutions stand on these measures, which need to be an ongoing part of a broader set of metrics used to guide institutional performance. Just as the healthcare industry was transformed by patient surveys a decade ago, higher education will be transformed by the coming data revolution. It will be an exciting new frontier that will yield a dramatic improvement in performance on factors that matter most to the relevant constituents and consumers of higher education -- and to the aims of its collective, powerful mission, as well.

This blog post was adapted from an article published in the July/August 2016 edition of Trusteeship Magazine.