Food insecurity -- or the lack of access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food -- exists at some level in every country. But until recently, there was not an individual-level measure to identify common causes and risk factors of food insecurity around the world.

This all changed in 2014 when the Food and Agriculture Organization's (FAO) Voices of the Hungry project developed an experiential measure of food insecurity -- the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) -- that tracks food insecurity on a global scale through Gallup's World Poll. The scale is based on eight questions ranging from whether people worried about running out of food because they lacked funds or other resources to whether they had gone without eating for a whole day for this same reason.

Using the new FIES measure, a team of U.S. Department of Agriculture researchers in 2017 published the first paper to identify and examine the common determinants of food insecurity in 134 countries.

Key Findings

Despite the diversity of global populations and differences in governments and policies, local economies, labor markets, and agriculture, the FIES provides researchers with a mechanism to identify the characteristics of the typical food-insecure person around the world.

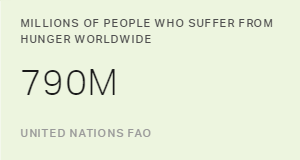

In a recent study, USDA researchers used the FIES to identify and examine the common determinants of food insecurity in 134 countries. The research team found that 27% of the global sample fell into the food-insecure category. And, as expected, food insecurity was highest in low-income economies, followed by middle- and high-income economies. Roughly half of the population in low-income economies experienced food insecurity, compared with 10% of the population in high-income economies.

Using a series of linear multilevel models, the research team identified five characteristics most strongly associated with the likelihood of experiencing food insecurity:

- low levels of education

- less social capital

- weak social networks

- low household income

- being unemployed

They also found that across all rankings of economic development, low levels of education, weak social networks and less social capital all played a large role in the likelihood of experiencing food insecurity.

But at the same time, there were a number of differences in the determinants of food insecurity across these rankings. For example, researchers found that the associations between food insecurity and gender, the number of adults in the household, rural status, employment status and GDP per capita all vary by development ranking.

In fact, while GDP per capita was associated with the largest decrease in the likelihood of experiencing food insecurity for low-income economies, it was not statistically significant for middle-income economies after accounting for other individual, household and country-level characteristics.

Conclusions

The research team concluded that these results reveal the need for country-specific development policies regarding food insecurity -- and suggest that a one-size-fits-all approach to development programs is unlikely to be effective.

Finding out who the world's food insecure are -- and identifying the factors that put others at risk -- can help governments and aid organizations target their assistance. The USDA team's study is the first step in using measures such as the FIES to document these risk factors across the globe.

Read the full paper, "Who Are the World's Food Insecure? New Evidence From the Food and Agriculture Organization's Food Insecurity Experience Scale."