Story Highlights

- Views of personal, national economic situations strongest predictors

- People in countries with higher unemployment more negative

- People with better living standards more positive

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- People's views about their national and personal economic situations may be the strongest predictors of their attitudes toward immigration, according to a Gallup study of attitudes toward immigration in 142 countries. Worldwide, the study finds people who say their economic situations are "poor" or "getting worse" are more likely to favor lower immigration levels in their countries. The reverse is also true: Those who see their situations as "good" or "getting better" are more likely to want to see higher levels of immigration.

These findings are among those featured in the International Organization for Migration's new report, How the World Views Migration, which is based on Gallup World Poll interviews with more than 183,000 adults across 142 countries between 2012 and 2014. Adults worldwide were asked two questions about immigration: "In your view, should immigration in this country be kept at its present level, increased or decreased?" and "Do you think immigrants mostly take jobs that citizens in this country do not want (e.g., low-paying or not prestigious jobs), or mostly take jobs that citizens in this country want?"

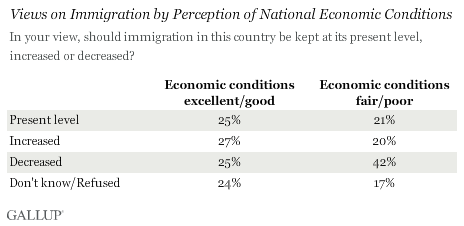

Globally, adults who believe economic conditions in their countries are "fair" or "poor" are almost twice as likely to say immigration levels should decrease (42%) as are those who say conditions are "excellent" or "good" (25%). The same pattern is evident when examining people's outlooks for their countries' economic future -- those who say conditions are "getting worse" are nearly twice as likely to say immigration should decrease as those who say conditions are "getting better" (48% vs. 25%, respectively).

In nearly all regions of the world, people who see their economic conditions as excellent or good are more likely to have positive outlooks on immigration. These gaps are quite large in several countries, including the United States (46% vs. 25%), Germany (43% vs. 25%), Canada (41% vs. 21%) and China (22% vs. 11%).

Africa follows the global pattern, but the differences in attitudes toward immigration based on economic views are not as large as in other regions. In addition to Africa, in some countries, such as South Korea, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Jordan, Israel, Iraq, Malta, Belgium, Macedonia and Venezuela, there is no or very little difference in attitudes toward immigration by people's perceptions about the national economy.

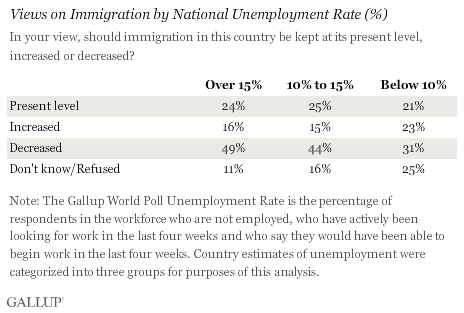

People in Countries With Higher Unemployment Rates Are the Most Negative

Adults who live in countries with the highest unemployment rates show the most negative attitudes toward immigration to their countries. Nearly half of adults in countries with unemployment rates higher than 15% believe immigration should decrease.

People's personal employment status also strongly relates to whether they want to see lower immigration levels. Compared with others in the workforce, those who are not working but are actively looking for work and able to begin work are considerably more likely to want immigration decreased (40% of the unemployed vs. 33% of those not unemployed).

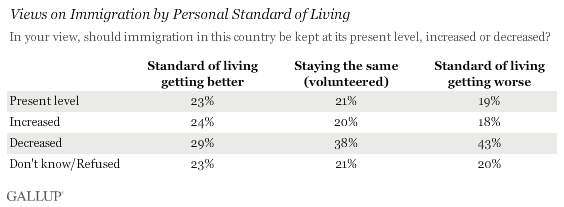

People With Better Living Standards Are More Positive Toward Immigration

In all regions, personal economics -- both in terms of subjective measures such as perceptions about one's standard of living and objective measures such as household income -- relate to people's attitudes toward immigration levels.

Adults who are satisfied with their standard of living and feel that it is improving are more likely to support increasing or maintaining immigration levels in their countries. As with their outlooks on the future economic conditions in their countries, there is a stronger relationship between residents' attitudes toward migration and their perceptions of their future living standards than of their current situations. Residents in all regions who say that their standard of living is "getting better" are more likely than those who say it is "getting worse" to say that immigration should stay at its present level or increase, and they are less likely to want to see it decreased.

Implications

People's outlooks on their national economies, personal standards of living and (to a lesser extent) household incomes are strong indicators of their views of immigration, but they do not strongly predict people's opinions about whether they think migrants compete with native workers for jobs in their countries. People's views on job competition between nationals and migrants are, however, related to opinions about immigration levels. These attitudes will be analyzed in Gallup's next article in this series.

Frank Laczko and Marzia Rango of IOM were contributing authors to the How the World Views Migration report.

Survey Methods

Gallup conducted a total of 183,772 interviews in 2012, 2013 and 2014. Most data for this report were collected in 2012 and 2013. In 2014, data were collected for Canada, Australia, Hong Kong, China, Switzerland and Norway. For this report, typically 1,000 interviews were done per country. A few countries such as India and China have higher sample sizes (more than 2,500 each), and all former Soviet Union countries included multiple survey administrations with a minimum of 1,000 interviews per administration.

With some exceptions, all country samples are probability based and nationally representative of the resident population aged 15 and older. The coverage area is the entire country including rural areas, and the sampling frame represents the entire civilian, non-institutionalized, aged 15 and older population of the country. Exceptions include areas where the safety of interviewing staff is threatened, scarcely populated islands in some countries and areas that interviewers can reach only by foot, animal or small boat. In Gulf Cooperation Council countries, at the time of data collection Gallup was able to interview only nationals and Arab expatriates.

Telephone surveys are used in countries where telephone coverage represents at least 80% of the population or is the customary survey methodology. In Central and Eastern Europe, as well as in the developing world, including much of Latin America, the former Soviet Union countries, nearly all of Asia, the Middle East and Africa, an area frame design is used for face-to-face interviewing.